If you are like me, you have wondered what mysterious steps were taken for our brain to develop from a simple, instinctual one to one of human intelligence. The answer to this question will always be a speculative one. We cannot go back in time millions of years, nor can we ever understand exactly what is going on in the mind of an animal—not that we have a clear idea of how our own minds operate. Perhaps, as evolutionary psychologists believe, there is not that much difference between the animal and human mind, but we will still need to explain how small differences have allowed humans to have separated themselves drastically from the rest of the animal kingdom.

What small steps have allowed more basic animal thinking to evolve into the minds that have built cultures, created art, conducted science, and organized civilization? What do we mean when we say we have a reflective consciousness or that we are self-aware?

There are many steps and diversions on the evolutionary tree and many steps more as a culture develops, but one feature seems to have been a necessary initial step towards human’s ability to think. That step was improving our ability to predict and simulate the future. Let’s begin with what this may have looked like in our ancestors.

Animals Who Look into the Future

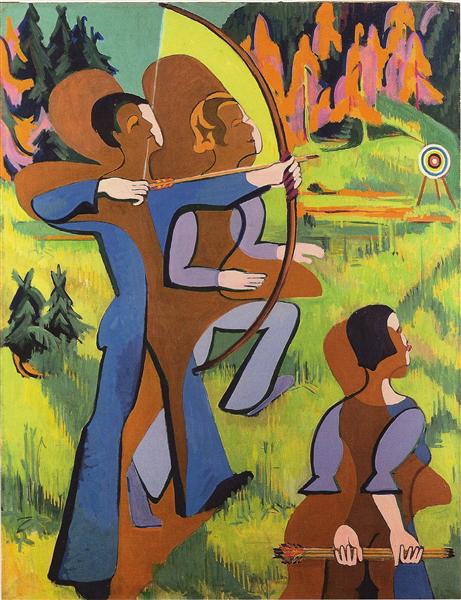

In The First Idea, authors Stanley Greenspan and Stuart Shanker reference the documentary The Chimpanzees of the Taï Forest to show us how intelligent non-human animals can be. The documentary shows chimpanzee tribes engaging in complex hunting techniques. They note that it takes twenty years for a chimp to master the hunt, and the ones who were most advanced were able to predict how a hunt would unfold even before it started.

The documentarians Christophe Boesch and Hedwige Boesch-Achermann describe that one chimpanzee would “suddenly run away from the hunt in a direction where we could see no monkey. It was only by following him that we realized that he was simply thinking further ahead, predicting precisely the further movements of the prey, estimating the time he would need to climb and very cautiously so as not to move any branches that could betray him, position himself high enough, and dart up in a perfect surprise attack when the prey entered his tree.” They go on to explain that the chimpanzee was predicting the actions of the prey, the responses of the other chimps, and the prey’s responses to the chimps’ responses. A lot of various information must be used to accurately predict how to get ahead in the hunt.

Clearly, the chimpanzee demonstrates a higher level of thinking than most other animals, but what does this entail about the consciousness of the animal? To exercise this intelligent ability, the chimpanzee must turn its attention to a sort of fantasy in which they can play out a possible scenario in their heads. Attention will be moving through ideas rather than moving around the local environment. This is different from instinct or habit, where animals have complex behaviors without consciously predicting the outcomes. Instead of only responding to the local environment, we think and plan and predict possible outcomes before we act. This ability is comparable to our ability to make goals. We get an idea of what we want, and we develop a reasonable way of getting to that goal by the fantasy of how that goal-seeking process will play itself out.

Goals: Anticipation Leads to Abstract Thought

What both the chimpanzee and the human can do is create goals in the mind. When we say goals, we typically will mean our seeking of an outcome which is not present, something that requires striving. We do not strive to eat the meal right in front of us, we just eat, but we strive to put a meal together as soon as we get home. In our minds, the meal is abstract, we can think about it (the goal) as an ideal or however we want; we just need to actualize that goal. We can create an image of a desired outcome or object, and predict how we might get it. Or in the case of avoidance goals, we predict how we might avoid an imagined outcome.

The chimpanzee, in our example, may not even have seen the prey to know what it is and that it must find a way to hunt it. It may have found clues which indicate the prey and bring it to mind. The chimpanzee positions itself in the hunt, not because it does so by instinct nor by short-term pleasures; it does so by constantly imagining how the hunt may run its course. A greater reward is down the road; a larger pleasure will be much better than many small ones. The need to anticipate outcomes has led to an ability to create conscious goals.

For accurate anticipation, an animal must be able to have somewhat accurate ideas of the rules of reality in their minds. They must be able to be able to create scenarios that must both be realistic and serve the motivated goal they may be seeking. The elements of a situation must have implicit definition in our mind. Often that is a simplified “if-then” sort of idea of the relationships between ideas: if prey goes left, then chimps will go left. Only with these implicit “reasons” can we play out a complex scenario in order to predict and achieve long-term goals.

For example, lots of animal clean themselves and practice hygiene which has long-term benefits. However, the human may be the only animal to consider it to be promoting “health” or “appearance.” Other animals may do it by instinct or pleasure, but we’ve created many reasons surrounding general hygiene as a long-term goal. For us to think like that means that we give soap and water an essence, and create ideas for how it interacts with our skin, and how this results in a future of greater reward. But in our heads, we have, unless well-versed in chemistry and microbiology, a simplified, and often metaphorical, idea of what is going on when we clean ourselves in the shower: “soap attacks bad germs.” This has altered the ways in in which we practice hygiene from an instinctual way, to a cultural or scientific way. Oversimplified metaphors for hygiene can extend into reasoning that accepts dowsing ourselves in disinfectant as a good path to health.

So, we have both the ability to predict “if-then” patterns from experience, and we are able to abstract out parts of things which define something according to its utility in our goal-striving. This makes a solid bedrock for how we have begun to do what we call logical reasoning.

Intellect Is Still Prone to Delusion

Being able to predict outcomes of complex scenarios, requires implicit definition of things so that knowing these definitions allows us to logically play out these scenarios. The chimpanzee must have in its definition of the prey a limited number of possible moves it might make, and it must have general reasons for why it must move in such a way, so as to best predict what may happen given other possibilities. This is an incredible ability to have! However, it can be as misleading as it is helpful.

First of all, this intellect is still just as emotional as the actions which we condemn as irrational. Although, I do not believe in the dichotomy between emotion and reason, it is worth noting that rather than opposing each other, they give rise to each other. As mentioned earlier, the intellect gives us a picture of reality within the framework of our goals. We do not need to know many aspects of reality which do not serve our goals. So where reason gets lost is in the oversimplification of the essence of an object, or in the ignorance of parts that we think are irrelevant to our goals. So rather than being condemned as emotional, behaviors and thoughts should be judged by their complexity and inclusivity.

Someone could act like an ass to you, but instead of getting angry and yelling at this person, you control your temper, as a good member of society would, and define that person as an idiot, forever being prejudiced towards him and always looking down on him. We will be calm and composed, but harbor a resentment to that person and anyone who has similarities with that person. Although we have avoided a violent, emotional confrontation, we are still living with a rationalized anger which exerts itself through perception, definition, and ideology. Now we can think and dread or anticipate emotional events far in the future instead of reacting to them. This can cause emotions to build onto each and multiply into very irrational actions.

This goes not just with frustration and anger, but with anxieties and desires. They no longer only inhabit the current situation, but they influence the thoughts we have as we anticipate and reason about outcomes. Our forethought might be more intellectual, but it may not be any more truthful than our feelings.

One of the general drawbacks of this is similar to what psychologists call “functional fixedness.” Once we have clearly defined something with its essence, and treat it as if that was all there is to it, we have closed ourselves off to a large portion of reality, without even being incorrect by stating a fact, making our intellectual delusions even more insidious than those which we know to be intuitive. It is difficult to believe you are wrong when you state a fact, when the only reason you are wrong is because that fact was far too narrow. We have to honor the fact that the world is far more complex.

All the material and objects in the world can be conceived as having multiple essences through which we see them, and several more essences for which we can never see.

“Now that I am writing, it is essential that I conceive my paper as a surface for inscription. . . If I wished to light a fire, and no other materials we by, the essential way of conceiving the paper would be as combustible material.”

William James

In another place William James continues this idea:

“A man is such a complex fact. But out of the complexity all that an army commissary picks out as important for his purposes is his property of eating many pounds a day; the general, of marching so many miles; the chair-maker, of having such a shape; the orator, of responding to such and such feelings; the theatre-manager, of being willing to pay just such a price, and no more, for an evening’s amusement.”

Tying this back into the idea of how our predicting the future is the origin of the conceiving a logical world, we realize that it is a limited view of the possibilities in life that solidify some people and things as having one-dimensional essences. It is a need for a security in the future that builds simple mental worlds. But this only prepares us for a predictable life, which hardly resembles the one we actually live. It takes an openness to the world’s possibilities to correct the narrowmindedness of so-called intellect.

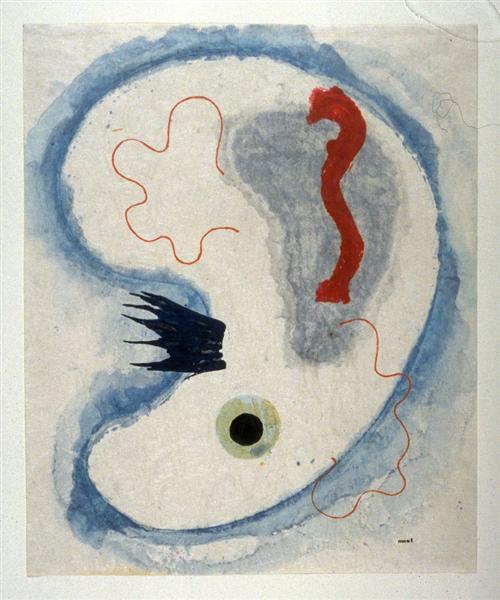

Art: Creative Attention and Greater Understanding

I don’t think the solution to this dilemma is to suggest all reasoning is folly or that one should stop thinking logically because it is no better than acting impulsively. What I think this means is that we must acknowledge the emotionally-motivated, future-tense elements of all our reasoning. There is something biological driving our reasoning no matter how intellectually honest. We can be compelled to pursue a fantasy through nearly infinite means, and it may be through philosophy, and it may be through acting boorish and impulsively.

We must understand, first off, that while we are thinking intellectually, we are pursuing, above all else, a future fantasy which vaguely describes a goal we might have. The search for truth is never a totally honest one, there is always some angle in which we see it that alters the way we pursue and present it.

Our ability to predict and prepare for the future perpetuates our polarized and simplified views, but it also gives us the ability to expand our world. By being able to create our own fantasies, we can create a transcendent one, and pursue it by using practices that are used in many traditional spiritual paths. We are allowed to have a transcendent fantasy, one which does not rely on one’s positioning in the world, but the quality of one’s own being. Rather than fantasizing about climbing the social ladder, the fantasy is on perfecting one’s experience. This is not a self-improvement where we aim to improve objective parts of the self, but a practice where present experience improves future experience.

It is a tenant of Buddhism that we can continually try to improve our spirit. No matter how evil or painful the suffering, every moment is an opportunity for spiritual practice.

In a sense, it is the opposite of thinking in order to better one’s place in the practical world; this is to practice to better one’s place in the thinking world. Religious and spiritual paths have sought this transcendent goal, but I think the artist hits most directly on the problem I have been describing in this article.

The artist works through an objective medium in order to express or alter the experience of their subject. Creating art is a practice which improves oneself not in an objective way but in a way in which you experience the world. However, any kind of practice or ritual that intentionally improves one’s subjective experience and could merit being called artistic in this narrowly defined sense.

Creative work is not trivial nor is it a means for an end. Creative work uses presence to improve the future by changing the way that we see the world. We have already created so many definitions of things that we need to be able to see them from new angles, art does this often with trivial things, such as in a still life painting. Poetry and playing with words give us the opportunity to adjust the subjective meanings of our language to make them more complex. Art disrupts our definitions so that we create more complex understandings of experience. It is not only good for our souls but it prevents us from have far too polarized or narrow-minded perceptions of things.

I believe that as long as we have this ability for forethought, we ought to use it for improvement of experience as well as its practical uses in preparing and building the up our world, and using it as equipment. We cannot take this ability for granted as merely a means of preparing for biological survival, but also allowing us to grow our understanding.