Experts in linguistics and psychology and sociology have debated whether our language creates our perceptions or if language is logically derived from our instincts and perception. Is the way we understand the world determined by our biology and physical world, or is it more or less arbitrarily determined by the powers of our culture? The assumption in these arguments is that the truth is one way or the other.

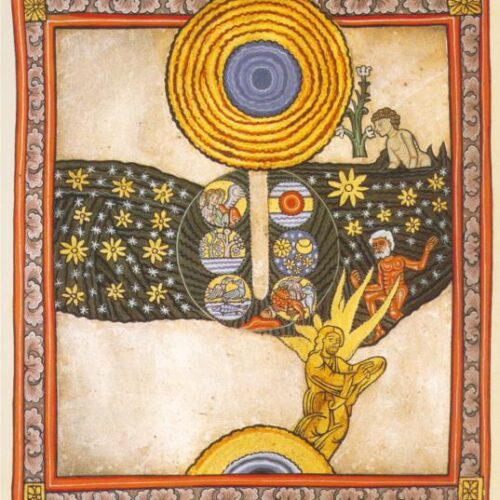

“The Polish-born anthropologist Bronislaw Malinowski (1884-1942) argued that cultures came about so that the human species could solve similar basic physical and moral problems the world over. Malinowski claimed the symbols, codes, rituals, and institutions that humans created, no matter how strange they might first see, had universal structural properties that allowed people everywhere to solve similar life problems.”

Marcel Danesi in Messages, Signs, and Meanings)

Culture is created out of a symbolic rules and meanings which are meant to solve universal problems. But can changing culture and the language we use change those universal problems, or is there basically one way of seeing these universal problems?

Isn’t Language Artificially Constructed?

Let’s begin with what is obvious about the “constructivist” perspective, the idea the much of our language and culture is artificially created. It is very clear that we are born, not only into a physical world, but a world of man-made representations and a system of cultural meanings. It is also clear that cultures can have extremely different ways of seeing the world. Especially when learning of the cultures which are more isolated from the rest of the world, we find that the same human beings can experience the world with great diversity. Peoples are different in a large part simply from the culture they were born into, but in keeping with Malinowski’s view, these differences aim a more universal set of human problems.

But how can we be sure that the way we understand desires or emotions through language is directing us towards something real? Language can be deceptive. And is an apparent “universal human problem” only going to be relevant in our particular culture?

Our language creates structures of concepts and logical relationships between ideas that plays a role in all the thoughts we have. If we were to be decieved by biased language, we would have a very difficult time recognizing it.

“In every waking moment, your brain uses past experience, organized as concepts, to guide your actions and give your sensations meaning. When the concepts involved are emotion concepts, your brain constructs instances of emotion.”

Lisa Barrett in How Emotions Are Made

It is clear that symbols (language, gestures, rituals, meanings) account for a large diversity in human behaviors and experience. Are these differences the just different means to the same ends? Can we ever understand these ends? Is there hope to intentionally change what we accept as “human nature” by changing the ways in which we represent our experiences? Or is there even human nature behind the language of gestures and social interaction, or just a void?

Language Reflects Natural Importance

But language is not totally determining of the way we see the world. Sometimes the way we inherently see the world determines our language. Clearly if we got rid of the word “hair,” we would still be seeing the stringy stuff on top of people’s heads. Even after several generations without the word would probably still recognize it as a distinct, but nameless, object—most likely a new name would be created. But this is because hair is such a distinct and relevant object in our lives. But this doesn’t really change how we see the world, only in how we describe it.

This is the argument of the people who oppose the “constructivist” theory. They would say that language and culture are merely a reflection of the reality of our biological systems interacting with the physical world. They would say that the important, essential distinction between red and the other colors is why we have the word “red.” Every element of culture is something that is determined by biological forces rather than culture changing biology. There may be some freedom in how we organized and group things, but overall the same result is attained: an expression of human nature.

It may be trivial to argue about how “hair” and “red” are thought of as natural kinds, but this argument can extend into the more difficultly defined social-emotional realm. Does it matter what we call these things and how they fit into the symbolic order of language that changes the way we actually act in accordance to what we might call human nature?

In their book, Metaphors We Live By, Lakoff and Johnson claim that we structure our lives according to metaphors which can only exist due to a symbolic system of language. “Love,” for instance, has many potential metaphors, all of which aim at something biological, but are culturally created and are more relevant in different situations. “Love is madness,” “love is a collaborative work of art,” or “love is an object to be placed on display” are some of the examples given by the authors. All of these culturally-determined attitudes towards love have very real consequences towards our actions. But there must be some biological, universal “human nature” operating behind all of that, right?

Language Is an Agreement for Solving Universal Problems in Specific Situations

What we have to keep in mind, is that our language is not a direct result of a single organism’s tools for problem solving. Language and culture are a product of agreement in solving those “universal human problems.” For better and for worse, this agreement travels through time and is given to future generations.

“Even the most elementary communication is not possible without some degree of conformity to the ‘conventions’ of the symbolic system.”

Talcott Parsons

Because language comes from a social collaboration, these agreements can be skewed by the potential biases of social life. Some ideas arise out of groupthink. Some people have more power than others, and they can affect how we have our tools for problems solving laid out. Authorities narrow down what we might see as the universal problems of human life. The philosopher Michel Foucault defined true power is the influence over our language, because that is how our thoughts are structured.

The metaphors we use in describing what we consider to be “universal human problems” tend to skew the universality into the specific problems we deal with in culture. For this reason be are blind to what is “human nature.” Part of the problem can be helped by having honest conversations outside of our own cultural situation.

It is clear that when you step into another culture or domain and learn something new, it changes your perception. For me, I have just begun learning native plant species and now it changed the whole way I see a forest floor. It is not that language changes the world or my ability to see, but it has opened up more specific elements of my world which may contribute to something universal. Just by being given names of plants and being around people that talk about them, a new world has opened up in front of me, adjusting how I see the world in a more holistic way.

Luckily, we are able to traverse microcultures and learn new things. The domain of psychology and that of nature and plants and very different, but allowing them to “solve” meaningful problems in my life connects them together.

Culture, no matter how different or strange, is a way for groups of humans to agree on the most pressing problems and figure out how to solve them. Language is both biologically determined and manufactured.