When we get into arguments, say with our partner, we always are trying to make reasons to support our positions. We argue about the trash, the dishes, how to raise the children, etc. But as we quickly learn to know, our arguments are about more than they what they appear to be. These arguments are more about being understood, important, and loved. This is also the case with words, and the logic of language itself.

Even the way we talk about language itself makes us think that we are intentionally packing up ideas in words and sending them over to be unpacked by another person. This is the conduit metaphor that George Lakoff and Mark Johnson talk about in their book Metaphors We Live By. For the most part, this metaphor can be very true but it misses the fact that there is much more to conversation than the conveying of discrete ideas. One thing that is outside of the packed box of language is the connotations of speech.

We know what denotation is. We have an idea of the strict definitions of words, or at least most of the time we know when a word fits based on the dictionary definition. But that is only a one of the ways that we choose and use words. We may wish to compile a perfectly complete set of symbolic rules in a logical manner so that we can always be logical. But language and other representations will always have their psychological meanings.

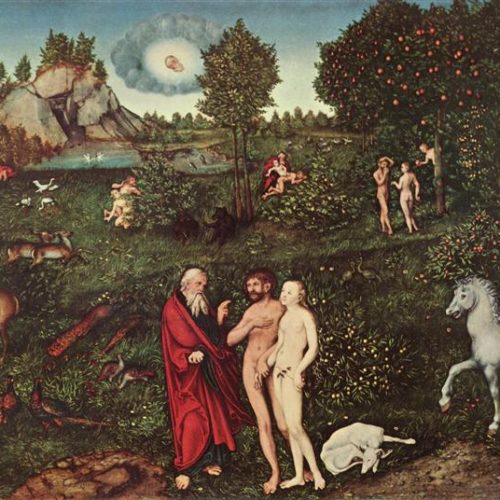

Denotation tells us the relationships between words, connotation is what the words actually mean to us. In a past article I talked about symbols and analogy. Analogy is a sign that has connection with the representation it signifies. Words are symbols which are arbitrarily created. The word “red” does not resemble in any way the experience of the color—that is what symbol means. But the word “red” also has analogous connections based on how we use and hear the word. This is where we get true psychological meaning in a language of symbols.

Symbols Are Defined by Their Use

“If we had to name anything which is the life of the sign, we should have to say that it was its use”

Ludwig Wittgenstein

With anything that we presume is created and used, we give it its essence by what it is used for. A hammer is used for pounding in a nail. If it cannot do that, then it is not really a hammer, or it is a broken one. The essence of the tools in a language can be how we finitely define it in the dictionary, but the true psychological essence is based on how we are familiar with the words being used. If certain language is used to hurt, even if the words are neutral and true, they can still do their damage.

The true psychological definitions in language come from usage. This is true for emotional language, but also true for simple objects. For instance, the regularity in which we see things paired with words affects what we think the essence of the word is. In How the Mind Works, Steven Pinker cites some examples. He says people consider 13 as a better example of an odd number than 23 and a mother as a better example of a woman than a comedienne. As you know 23 is just as odd, and a comedienne just as much a woman, but our experience with these labels misleads us into thinking one is a more essential example.

This is a basic, original quality of our minds, especially in how we learn language. Children base the definition of the word by how it is used more than the actual definition. When asked what a robber is, a child will point to description of suspicious looking man (perhaps resembling a cartoon robber) even if the child knows that man hasn’t stolen anything. But the child will rarely ever consider a robber to be man at home stealing credit card information on the computer. This example is based on an example from a text book written by Robert Sternberg called Cognitive Psychology.

We still have this very same mind, attributing essence to things based on the usage of the word rather than definition. Once we become accustomed to the structure denotations give us, we get more nuanced in our ability to describe the world, but we still have the tendency to have the gut-feeling definition of things based on how they are used in everyday conversations. This is not a flawed way of logic but an absolutely necessary skill in having social interactions.

Conversation and Psychological Definition

Our conversations, which are built from representing things to others with verbal and nonverbal symbols, is never just about the literal denotations. The definitions of the symbols we communicate have meaning of course, but also have psychological impact in terms of how one has heard it used. Even simple questions and efforts and interactions have roots in an emotional gesture or drive. Stanley Greenspan explains that asking, “what did you do today?” is not asking for the generic list of tasks. It asks what was emotionally significant. It implies what the asker might find significant as well. To read off a list would be very comical. “What did you do today?” is an emotionally driven question, which can sound accusatory or kind based on connotations and subjective experience.

Even rational conversations where both people are honestly looking for some kind of truth, are not the pure rational discourse that we think they are. One still has to ensure that the words being said have generally agreed upon connotations. The same two people who come to an agreement with a proposition may have very different ideas of what is right about it based on their individual experiences with the facts involved and how they are communicated between each other. That is why it is such a useful tool to parrot back what people say in your own words, to have a mutual understanding.

It is also possible to say logically coherent things and be wrong. There is some validity in the people that say, “you’re not wrong, but…” As we know from the news, headlines can briefly describe the situation that literally happened but in a way that is a lie just by using the labels and the verbiage that has implications that go much further.

Although it is still helpful to have definitions for words and strict meanings, we cannot ever hope to obtain any important essence from language without the connotations and how the words are traditionally used. Merely having well-defined language alone will not help us in better communications.

‘There is no reason to look, as we have done traditionally—and dogmatically—for one, essential core in which the meaning of a word is located and which is, therefore, common to all uses of that word. We should, instead, travel with the word’s uses through “a complicated network of similarities overlapping and criss-crossing”’

Biletzki & Matar in the “Ludwig Wittgenstein” article of The Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy

But what is required in bettering communication is conversation and word usage itself, especially on the side of listening and interpreting.

Freedom In Connotation and the Effect of Emotional Health

There is no ambiguity in the denotations of things. The literal definitions of words and facts we say are what they are. We have very little freedom in how we take the literal statements we hear. This may actually be a very comfortable realm to remain focused on. “Just stating the facts” is a secure, straightforward position where we can always claim to be on the side of logic, but it ignores a much more ambiguous feature of all language: connotations and the freedom of interpretation.

We can generally understand the literal meaning behind statements and culture, but the historical and personal contexts are difficult to decipher. Worst of all, it is unlikely that we can ever know what some words mean to others because they have had different experiences with the same things. That is what makes denotations great to have; it is a consciously agreed upon way of speaking. But even then, when we speak, we have to allow for the fact that the listener not only has a different idea of what you are saying, but that they have the freedom to interpret it however they like.

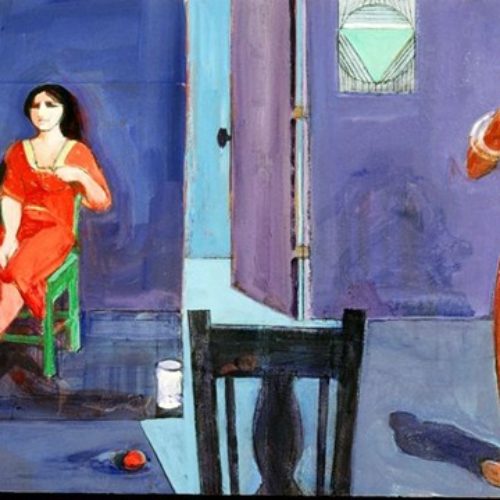

Typically, with the more freedom we have to interpret things, the more it will be based on our current and historical emotional dispositions. Emotional reactions to things often mean that there is freedom for interpretations. It is good to always hang on to the denotation, on the literal symbol, but the more emotional, essential meaning is up for freely interpreting and remolding.

“The grapes are so incredibly beautiful that you can’t help but be thrilled. If you aren’t—if you only see someone’s profit or that in another month there will be rotten fruit all over the ground—someone has gotten inside your brain and really fucked you up.”

Anne Lamott in Bird by Bird

It is always where we have the freedom to interpret where our past, our emotions, our fears, are allowed to interpret the meanings and contexts of situations and denotations. Perhaps, instead of using feelings as an authority on some matter, especially if they hurt you, you can see the emotional responses to things and realize that it comes from the freedom of choice, and the automatic choice is just the default you’ve been conditioned to have. Check out this highly interesting commencement speech on the choice of interpretation of literal events by David Foster Wallace.

Knowing and utilizing this freedom to interpret is the first thing we have to be aware of when we are listening to others. Their words may trigger some deeply rooted emotion, but to listen to them, you have to hear them in what they say, not what you say about what they say. We have the freedom to listen and therefore communicate with awareness of one of the largest barriers to communication. It is in this way we gain more nuanced ways of understanding the points of view of other people.