I have previously written about how attention functions to direct senses to novel or unpredictable things that we may need to react to. Attention focuses on a section of the world that is both important and unpredictable. We are more likely to pay attention to a living threat than an inanimate one, perhaps only because the living one is unpredictable, the threat is unknown and needs to be quickly reacted to depending on what it does, so it would be wise for us to be paying attention to that. We need to see every one of its movements to get away without harm. And once the object proves totally predicable, we can ignore it or react without attention; as it would be a waste to spend more energy than we need to on such a thing.

I have also written that it takes conscious attention for us to learn things perceptually. It is the way we actively look at things that divides the world up as it is into perceptions. The goal of the article today is to combine these two notions to see how we arrive what seems like a stable perception of the world and how emotion plays a role in changing and making that perception unique.

Uniqueness of Our Perception

We expect to see the world as it comes in, merely as a process which organizes sensory input into objects based on their physical properties that exist “out there” in the real world. It seems that everyone basically sees the same world exactly as we to. For the most part this is true, the raw data we get is basically a good representative of the world we all share. And the way our brain organizes it is mostly in terms of simple features that are practically immutable no matter what one’s individual experience is, as long as we are looking at the same world.

But we are actually very selective about what we perceive on a practical level. The world is far more detailed than we now see. We group objects as the same while they are actually unique in themselves, but they are not unique enough for us to think they are totally new. Subtle differences in some things go unnoticed while in others the same level of difference makes it totally new. This is because we have learned through an emotional pathway what discriminations are important and what are not. And we see levels of detail that are unique and more important to us. Understanding this mechanism could give us the tools and practices to change the very way we see the world, down to how our sensory system functions.

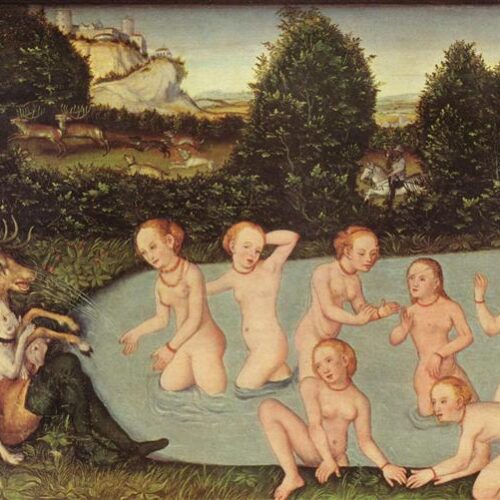

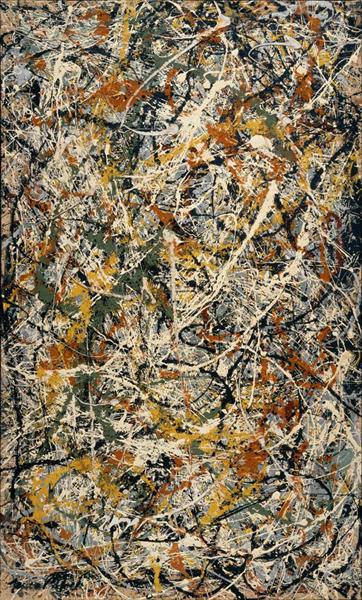

Imagine swapping, while no one looks, two Jackson Pollock paintings with the same color pallet. Would anyone notice? The differences are sensually obvious, but because there is no meaningful difference between the two. We often see the painting as a whole, and we do not make meaning out of the random whips of paint—assuming that most people are casual viewers of art. Even with the paintings side by side, we rely on the perception of an overall texture and colors of the paintings to tell us the difference. We need large categories to make sense of important differences. Fortunately for our survival, except for the art historian, noticing the difference between these two painting is not all that important. But by the end of this reading you may understand why art like this can be a sort of meditation.

For some things we have no structure for understanding its intricacies. It would be like being asked to tell me the directions of the individual blades of grass in your lawn. Unless you are fanatically motivated or can find a meaningful pattern in the directions of each blade, we will not perceive such detail in our lawns; only the overall patterns can be seen like tire treads or dead patches. We are selective when it comes to the amount of detail we process. It is in these area of selection where we have all grown unique in our perceptibility.

Aspects of Learning to Perceive

We cannot really imagine experiencing the world without the perceptual grouping of sensations, but the disarray of hearing an unfamiliar language demonstrates to us what it might be like if we suddenly lost this ability. None of the sounds have meaning and they apparently come as one unorganized stream of nonsense. Trying to learn what this language means without a teacher may give us an idea of how we’ve used attention to learn more complex perceptions.

As we spend more time listening to the language, automatically we begin to hear the subtle pauses and vowel and consonant sounds (phonemes). This is like the basic level of perception that we passively learn because of the organization of sensory organs and their ability to discriminate generally different inputs.

The dividing up of the sensory world is a fairly automatic process that we cannot directly control. In vision, colors, intensities, contours and lines and orientations seem to be rooted in the very basic level of sensation. But these smaller units must come together to form meaning, we cannot act intelligently without a meaningful world to act in. Thus, two more mechanisms follow.

Basic Affect: Curiosity and Uncertainty

Imagining that as new language explorers with a child-like wonder, we would find these sounds to be inherently complex and interesting, we would pay great attention to them, not sure if the sounds were important or not. These new noises capture attention. Are they dangerous? Is an opportunity presenting itself? This draws attention further into grouping the sounds into larger bits.

Attention will go to those things which are more complex and that move and change. This is an innate motivation that supplies a need for defining one’s situation in the world. This general exploring motive now goes by a few names: curiosity, uncertainty, nervousness, wonder, and several others.

Before we could explain or understand something complex, we felt a fearful uncertainty about it or, when in a safe situation, a curiosity about it. Most likely there was an element of both fear and curiosity in perceiving a novel object that captured attention. These two emotions seem to be very closely tied.

It seems to be movement and complex sensory data that grab the attention of infants the best. These things with movable parts are typically going to be important for the infant—they are often the caregivers. The things which cannot be understood by a glance are the things that provoke the curiosity or uncertainty instinct. The instinct of a capturing attention. This curiosity and uncertainty seem to be the main currency of attention and perceptual learning. Things which are salient purely in a sensual way, loudness, brightness, etc., will grab our attention with a startle, but it is uncertainty that will keep us looking, searching for the cause, or perhaps something else to come, and therefore learning.

The biggest factor in the motivation of attention is novelty of stimulus. Infants will look on to these novel things and see if they will have any effect on their well-being. Anything new, especially to an inexperienced infant, could be a threat or an opportunity. That space in our world where the novel thing has yet to fit, that space of the unknown, commands our attention. We want to notice the signals that predict its action. We want to see if we can trust it. But often these things are inert and we stop our perceptual learning at a general level of perception.

The goal of this curiosity-uncertainty is so that we explore the world enough where we get an understood and unexciting picture of it when it comes to the things that do not make a huge difference for us. We pay attention to things at least from the feeling of interest or uncertainty. When these feelings die, as we habituate to the new object, we produce space for normal and unexciting world not worth constantly watching out for. Now we can pay attention to the interesting stuff.

Motivated Perceptions and Higher-Level Perception

This curiosity goes so far as to get us to have our attention on the right places when one must act, but they are by no means all we need to do to survive; we need to connect the complex and interesting things to our needs, actions, and emotions. This may happen in two ways, each of which coexist and help each other out.

Let’s return to the foreign language analogy. When we begin to pay attention to the units of this interesting new language, we can tell what words have meaning because they carry emotional value in the speaker which the listener picks up. This may be analogous to sensations that automatically evoke affective responses in the perceiver. Things like this, which carry an innate emotional value could perhaps have been programmed into our genome. I talk more on these innate representations in a previous article. This section will focus on how we learn from experience what things are important to our well-being.

This learning has to do with our interaction with the perceived object. We can imagine that some of the sound patterns in this unknown language evoke an action in the speaker that may relate directly to our well-being. We must be able to detect these things and react.

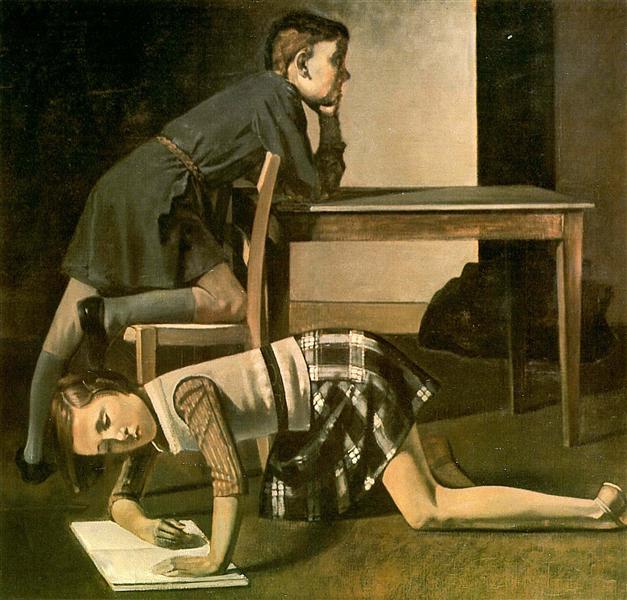

A chain of sights or sounds can become very important to a child because it means that if he or she responds to the sounds in a certain manner, a comforting caregiver will nurse the child. The child learns to negotiate and communicate its needs by learning to perceive and responding to cues of the caregiver. Through everyday perceptual learning, the child can predict outcomes based on subtle cues because of his or her natural curious attention and the perception’s association with the child’s own well-being. At this point in life the child is learning to perceive more acutely the things which it may signal the need to reaction.

This means that emotionally interesting things can be seen with impressive acuity. For instance, different faces have incredibly subtle distinctions. We can still very easily recognize different people, because we know that subtle information matters for how we should act. This is where affect plays a larger role in perception. Where some more neutral things start to lose their unique details, faces are attended to far longer, and we then get a more acute perceptions our of subtle changes on faces. We expend more attention in these things because they are not only unpredictable but they are vitally important.

These deeper levels of subtle perceptions make the world even more unique between us. Our personal experiences have changed the ways that we pay attention to things, and therefore, the scope of focus at which we perceive and grouping of perceptions most relavant to define things.

If the neural pathways responsible for intelligible perceptions are rivers, then affect is the water that carves the rivers deeper, and attention contains the bodies of water where the river will flow.

Reorganizing the Perceptible World

Improving one’s perception can certainly get us closer to an ideal Sherlock Holmesian perceptibility, where we notice minute details that can give us clues to meaningful outcomes. But sometimes an acute perceptibility for the wrong things can make one’s thoughts more chaotic.

Much of our room to grow in perceptivity is in the subtleties of human communication. Language and tone are subtle, facial expressions are subtle, gestures are subtle. We learned which of these we pick out are meaningful a long time ago, and that greatly affects our social abilities.

If we learned to be perceptive of only the expressions of others which required action, we could very well only be perceptive of negative emotions of other people. If we never had loving parental expressions to interact with or those expressions evaporated without interaction, we may not have created meaning in them, nor paid any more attention to them. Perhaps the negative, anxiety provoking cues are what we’ve come to recognize the most. For this reason, and in many other similar cases, we could actually be suffering emotionally and socially from our inabilities to perceive.

Our early lives can also create our ability for perceptions that gives us an edge on social and technical skills. When we think of a “perceptive” person, we generally think of someone who is able to recognize subtle cues generally regarding important matters. A perceptive person can tell what someone is feeling based on their unique expressions. Perceptivity is extremely important in building social skills and practicing the “subtle interplay” with people which is according to psychoanalyst Donald Winnicott, an essential component of love. Since we cannot change how our early development went, we must do what we can to ameliorate some of our perceptual blindnesses.

The Practice of Seeing

One route is by creating a technical goal. This is generally a straightforward path. We want to be great at birdwatching so we get someone to show us what qualities to look for in birds and we seek them out. Eventually we can easily see the difference between species, and our perception of a bird will never be the same, it will be layered with the details of its feathers and beak and breast. This is basically how we get technical skills.

A soccer player can perceive the subtle changes of the hips of the opponent to see where they are going next. Or a radiologist can detect a practically invisible anomaly in an MRI scan. These skilled perceptions are derived from our unique affects and motivations directing attention closer and carving their neural paths deeper. Perceptivity is an essential skill which can take lots of experience that only comes after being a veteran of a certain trade.

The problem with this method is that it does not teach us the values. We start with a value and we ask, “How do we perceive this better?” But if we do not know what we are missing, how do we know what to look for? If no one can tell us what to look for, how do we see it.

The solution is a more general approach to relearning perception. If we are always opening ourselves up to experience, we can continue our perceptual educations as long as we live. This starts with being able to attend to the world without reaction. Automatic reaction is what tells us that we already know what to do and there is no need to pay any closer attention to what caused the action. When we see things that are predictable and emotional, there is no need for attention, but we still react. But if we put an unreactive focus onto something, we can see what it is telling us as if for the first time.

Mindfulness is the practice I am describing. It is not looking for the secret giveaways of perceptual skills, like we do to learn technical skills, but it seeks a general attention to the task at hand. In mindfulness, we give attention to the things that we have done unconsciously for a long time, and these things begin to show their subtleties, and if these subtleties evoke an emotion, and they may evoke curiosity at the very least, they may reveal themselves in daily life with meaning.

In the end, my hope is to be a little bit more like the banjo maker of the poem “The Grain of Sound” by Robert Morgan.

A banjo maker in the mountains,

when looking out for wood to carve

and instrument, will walk among

the trees and knock on trunks. He’ll hit

the bark and listen for a note.

A hickory makes the brightest sound,

the poplar has a mellow ease.

But only straightest grain will keep

the purity of tone, the sought-

for depth that makes the lick sparkle.

[…]