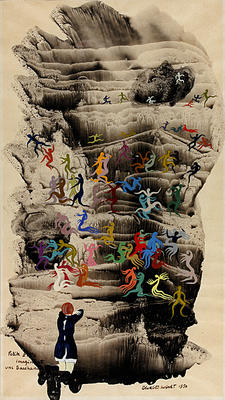

What makes up our conscious experience? It is not simply the thoughts which are most emotionally loud and relevant to your current situation. There are other, more mysterious, criteria which affect our thought patterns. Since Freud, we have been more accepting of the idea that some of our thoughts remain unconscious because their content is unwanted. The question is, what allows us to be aware of something? And what keeps it hidden?

While part of our experience exists as the objective, observable part, like words or actions or images, a large portion of the thought is ephemeral, bodily, and intuitive. It takes a careful ear to even hear the whisper of these elements. Layers and latticework of meaning surround every moment of consciousness. The object of the thought remains while the full content quietly disappears, sometimes convincing us that our thought was only the object, without its vast context.

This subtle unconsciousness has more effect on our patterns of thought than we may think. Its effect builds on itself and adjusts our thoughts onto a trajectory which we may have difficulty understanding the reasons for. One of the reasons comes from the peripheral meaning of a situation, in which the elements of a situation are defined according to a future need.

The Route to a Future “I”

Part of what makes higher-intelligence animals so impressive is their ability not only to act in ways which benefit their long-term future, but that they are able to this by imagining it. We imagine an “I” in the future and consider what it would take to make that a better situation. This forces us to reason our way into acting according to what would benefit the future. This is assisted by defining ourselves and our world with essential traits in order to imagine outcomes of our actions before we take them.

This future “I” is something we often strive for, creating goals to guide us to our desired world. We fantasize about the things this future “I” might have, the people that surround “me” with, and what those relationships might be like. This is an ideal which we, knowingly or unknowingly, strive for.

But the striving for such a goal forces us to subordinate present reality. We define things according to this striving, according to their usefulness in the future, including the things that are so intimate with our subjectivity, like feeling. When the mind is fixed on building a birdhouse, the hammer, nails, and wood contain necessity in their meaning, while most everything else in the tool shed and house are momentarily unessential. We do this with our deeper fantasies all the time.

Not only is it difficult or impossible to know exactly that the fantasized end is. We also always have strange, misleading, conflict-creating, means to reach that end. When motivated so strongly by one fantasy, other goals can be sabotaged along the way.

We can see the strangeness of the route to a desired end in how Freud interprets a dream. Freud saw dreams as fulfillments of these fantasies or wishes. For instance, it is conceivable that we dream of the death of someone we love. It may be absurd to suggest that the dreamer secretly wished that person dead. But the wish that is fulfilled, may be a consequence of the death, perhaps the opportunity to see someone who would be at that funeral, whom the dreamer desperately wishes to reconnect with.

“When the work of interpretation has been completed, we perceive that a dream is the fulfillment of a wish.”

Sigmund Freud

These desires are usually unconscious and infantile. Their content has to do with the future we hope for. We define our situations according to these unconscious goals, and the future is injected into the meaning of the present. This means that the wishes for the future “I” are partly in control of how we define even the most neutral objects of our world, influencing surprising things, such as our hobbies and perhaps the types of art and music we enjoy.

The Background of the Future

Thoughts and perceptions always contain more meaning than what is obvious. Sometimes we trust the objective, literal part too much. When we reduce our thoughts to “the cat is on the mat,” we are only remembering that linguistic-objective portion and leaving out the very subtleties that make the experience full and meaningful. The meaning of this situation has more going on that is unique to the individual that experiences it. While we conscious perceive things and have thoughts, we have a background intuitions and meanings that carry the stream of consciousness to further thoughts and interpretations. They may not change the perceived content of the thought or perception, but they change the feeling of the experience, the background, and perhaps the direction the stream of consciousness goes.

So in addition to our actions being controlled by only the current environment and emotional state we are in, our actions are controlled by the possible future consequences of those emotional states that may take us of or put us on the path to our fantasies. We then have emotions about our emotions, everything is subject to scrutiny by our hopes for the future.

Any objective perceptions are laced with desires for the future, supporting the idea that thoughts are always deliberating, in some way, about how to act in the future. Even if it is only a slight interpreting of the present to better suit the future.

Introducing the Censor

To consider the future above the present means that we must sometimes deny ourselves even the thoughts which do not support the future.

Sometimes we nearly totally censor thoughts which, in someone’s psychological history, has shown itself to be totally wrong and punishable. The many dark taboos of culture can easily fit in the category of thoughts which are completely censored.

We have built ourselves out of patterns avoiding the forbidden, and reaching towards the “oughts.” The censor becomes so embodied over time, we repress and totally censor some ways of thinking. This is why, as Freud found out, extreme cases of repression manifest themselves in bodily symptoms. The body wants something that the ego cannot handle, so it finds it’s released as a symptom.

But for the most par the censor agency does not erase parts of normal experience, it merely interprets in a way that supports one’s future and one’s self-definition. It is this kind of constant subtle censoring that we need to become aware of.

“Nothing, it would seem, can reach consciousness from the first system without passing the second agency; and the second agency allows nothing to pass without exercising its rights and making such modifications as it thinks fit in the thought which is seeking admission to consciousness.”

Sigmund Freud in The Interpretation of Dreams

But the censor does not need to hide things from us. Thoughts are already partly hidden, existing mostly as intuition surrounding language or mental imagery, which are very subjective, containing the depth of our past and future desires. All the censor has to do is interpret any ambiguous things in a way to steer the stream of consciousness away from the harmful thoughts and interpretations. It modifies the perception or fantasy to be useful for the future. But the present thought will still find its way into some kind of altered expression. For instance, we may never see the darker to someone’s life because we are supposed to like them and they are meant to be perfect to us. This is not a total delusion but it is not the full story, if there is such a thing as a full story.

It is the angle at which we see things that is changed. That is significant because much of the important parts of our thoughts and perceptions are nothing but angle. Every moment there is the opportunity to notice some parts, and ignore others, this is not a random choice, but it is a pattern that we have become habituated to, typically reaching for a future fantasy.

History and Unconscious

Why this censor is so difficult to understand for the individual is because it began its formation long ago, before language and rational understanding. We grew up naïve and needy, and could not understand why the adults did what they did; these misunderstandings became tortuous events.

Our end goals are unconscious, derived from repairing the depths of childhood inadequacies, unfulfilled needs, or threats of abandonment, even with great parents we can develop psychological difficulties from small but repeated incidents.

This is the source of our censored perspectives. These motives remain mostly or entirely unconscious, only being uncovered in psychoanalysis. Psychoanalysis is a practice of noticing what the censor is doing, and finding its motivation retroactively. But it will only work if the analysand becomes aware of the subtleties in the analyst’s interpretations. It will not be an objectively realized cure (like “your problem is Oedipal”), but one which adds new meanings to the same experience.

But we cannot simply say, “because I needed love…” to explain our behaviors. We need to notice the censorship first. The “intellectual” thought will not have the proper meaning until we see how it has been operating as a censor on nearly every moment of thought. Sometimes this takes a therapist to connect all the dots, but if not, it takes half a lifetime of noticing, mindfully and learning.

Noticing Every Altered Moment

This means that we do not necessarily need to immediately uncover the dark secrets our unconscious holds using clichés that are readymade to apply to universal problems. The “dark secrets” are precisely what we are hiding from ourselves. We must ease into self-discovery by noticing the limited angles we see the world in.

Seeing things as they momentarily are, holding back the definitions or rational aspects of them that have made us so oriented to the future, can bring one to see the world through a more universal lens, or a view from nowhere. And we can then begin to notice our tendencies towards the future. We can see the needs we have and hope for. What do the simple things in life mean to us?

This is every thought that we have. Every moment is an opportunity of uncovering our vantage point.