As discussed before, long-term memory sets down pathways by strengthening some connections and inhibiting others. We create many concepts by the bundling of active neural tracts. We have a somewhat malleable infrastructure for incoming information to be sorted and outgoing information to be coordinated. But that is not the only form of memory that we experience. Short-term or working memory lives in even more transient ways.

When we experience something in the last few minutes or seconds, that information lingers to help us interpret our current situation. It may even last a while longer if one continues to remind oneself of or ruminate on the recent information.

Working memory allows us to hold ideas in our mind just enough to be able to create an idea of our current environment where we can understand the situation to quickly interpret and react.

This idea has implications throughout our psychological lives from understanding emotion to the fabric of our social lives. We learn that context is everything, and it is the working memory which defines it.

Anatomy of Working Memory

Given that there are networks of neurons laid down as part of our long-term memory, we must look at working memory as existing within that same structure. This idea will turn out to be very helpful when thinking about subliminal information.

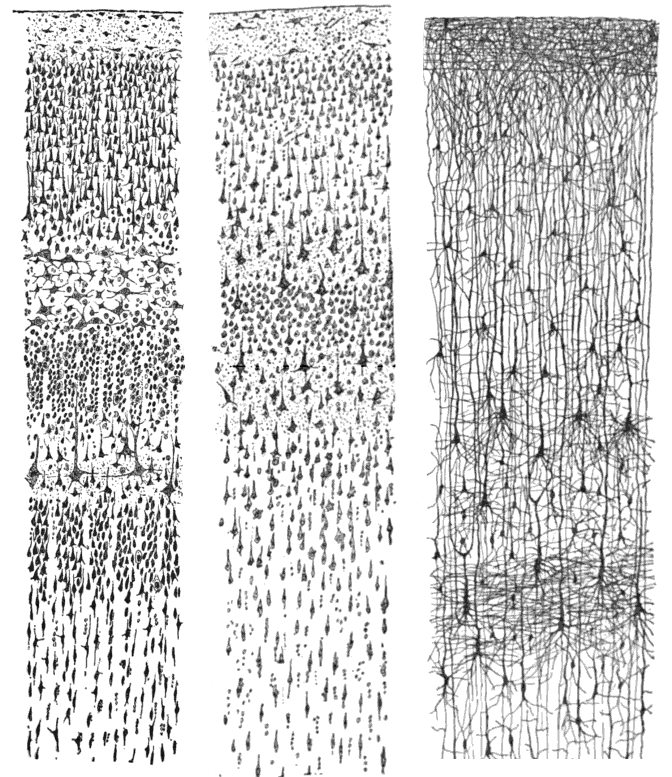

When neurons fire from an experience or thought, those neurons, and neurons associated with it, are activated and either remain active or nearing the level at which they could become active. Neurons fire in an all or nothing way, but their effect on subsequent neurons can be affected by their rate of firing. Each neuron is affected by several others, usually ranging from several areas of the brain.

The is no overstating the complexity of the brain, but hopefully this vague idea of working memory as a general neural state of nearing their firing threshold may not be an oversimplification. For instance, if in a new building we notice a clock, that memory would sit there with residual activation of neurons firing that are related to the “clock” concept and details about this particular one (location, color, for instance). When the inclination to know the time comes, the residually-active clock concept in our working memory will be at the ready to locate where the clock was. The residual information is easily accessed because it happened only a short time ago. Without this ability, we could easily get lost in new places.

All neurons have continuous baseline discharges of both excitatory and inhibitory incoming information, but here we focus mostly about neurons dealing with sensation, perception, and anything between those and the motor neurons that put us into action. For the neuron to fire, and memory to be materialized, the excitatory activation has to overcome the inhibitory enough to pass a threshold to active downstream neurons. Remember, the dormant working memory is a nearing of that threshold but not a guarantee of passing it. Passing the threshold, as far as the brain is concerned, is recollection. For something to be recalled, we require that extra bump across the threshold.

Typically, we thing of recollection as a conscious activity, but much of recollections does not need to be. Sure, when we have to explicitly recall where the clock is that we saw for the first time, we have to bring the location to full awareness. Or when we have to make a decision and consult many ideas, we bring things out of recent memory to inform a decision. But working memory is active in much subtler ways.

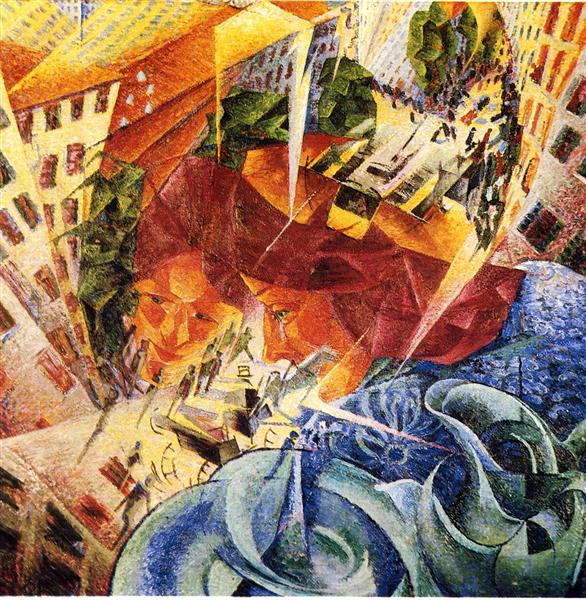

Working memory is most often “recalled” as an interpretation of a stimulus. That lingering activation is what interprets incoming information. Creating a solid interpretation of incoming, ambiguous information is what working memory does best. It interprets the present based on the contextual information gathered from the recent past. This allows a lot of information to sneak by, affecting our perceptions, but without being noticed.

Priming Effect

This job of the working memory is pretty well-accepted in the scientific community. Numerous experiments have shown how a recently viewed stimulus can affect the interpretation of later ambiguous information. Introducing this stimulus is called priming, and experimenters now use priming as a regular procedure in more advanced experiments because of how consistently it works.

An experiment that uses priming is often done by introducing cues which the participant may or may not find significant or interesting—often the cues are received subconsciously. Then the participant is put in a situation which requires judgement of ambiguous information. Usually the participants can be primed in such a way that will determine how they will act without their awareness. Priming experiments show us that the recent past is constantly being referred to for understanding the present.

Aronson, Wilson, and Akert give an example of how this happens in everyday life in their text Social Psychology. Imagine you are sitting on a bus and see a clearly alcoholic man outside the window. A few minutes later, another man on the bus is acting obnoxious and crazed. It’s likely you will interpret them as being drunk. But perhaps you are reading One Flew over the Cuckoo’s Nest while you are on the bus. You may interpret that same crazed man as being mentally ill.

We also will experience the priming effect in reading. Each previous sentence sets you up for the next one, and you unconsciously refer to the ideas left from reading previous sentences to understand, interpret, or add to the meaning of the present one.

What is the overall result of working memory? What is its most important function? It may be useful for many other things, but working memory’s biggest role is in creating an idea of a situation or context. It builds the ground in which we can see the figure. This is an essential quality of a psychological object.

Remembering the Situation

It is this working memory that can hold recent information long enough to give us an implicit feeling of our situation. In other words, having a vague or preconscious idea of the current situation is essential in how we react to everything, especially ambiguous things.

We may not realize how quickly we take in information. Thanks to the ease of processing of long-term memory, we can quickly receive information without paying any attention. And that information can be used for understanding the current situation without us being consciously aware of it. We are constantly being “primed” by our environment.

Our working memory is constantly defining the situation that we find ourselves in and interpreting the objects and events in that situation according to the context. We have all noticed some time or other how differently we act with different people. In his book Looking for Spinosa, Antonio Damasio notices that our automatic reactions to the same amusing story can be quite different in a strict business environment or a casual one. We do not even have to think about the opinions of the people around us, we automatically know our situation.

Emotion is born out of this perception of a situation and is therefore derived from working memory. Emotion contains a bodily response to the interpretation of a situation. It is rarely a reaction to an individual stimulus—that would be considered a reflex or rudimentary instinct. An emotion will come from a context that one is in and may or may not come from a single object or the situation as a whole without a distinct object. Being present is often an antidote to troubling emotion. Presence is, in this case, to free oneself of the momentary situation, to calm the nerves that are waiting to release their potential. Perhaps, through seeing things in their singular forms, without context, one at a time, we can inch towards true freedom and presence.