In human psychology, the ultimate effects of language on our experience tends to be ignored. We cannot study how our minds work or even discuss it without addressing the fundamental way in which we represent the world in the symbols of language. We may see through the eyes, but language is the lens we understand through; it is our tool for self-understanding and communication. Not only is it how we communicate what we know about ourselves, but it also penetrates the depths of psychology, allowing culture to saturate the most internal parts of the mind.

Here I will briefly talk about how we repackage and convey our experience and intentions to other people. This is how we get to the ability for representation of things that we cannot see. Representation is an important aspect to understanding of psychology, because, after all, it is through representing abstract things, that you can even have a faint but meaningful glimpse of what you will go on to read here.

Let’s start with the two forms of representing things: analogy and symbols.

Gestures and Analogy

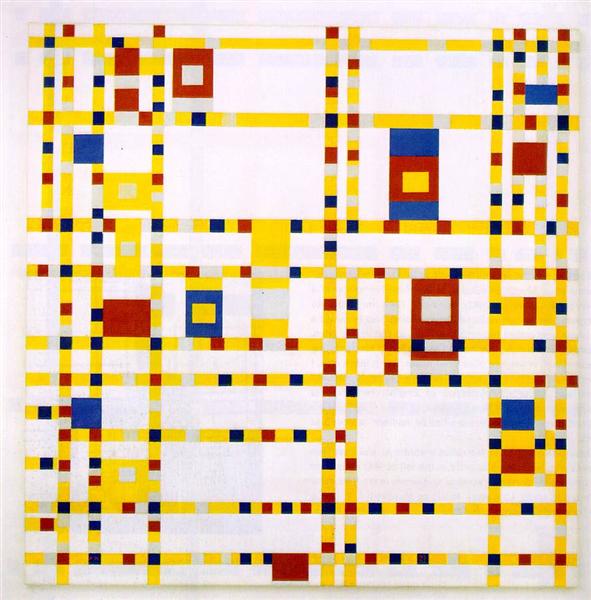

Analogy is a representation that carries some of the appearance or essence of what it represents. A drawing that imitates something in the world is an analog for that thing. Its appearance is translated from the original experience. The analogous sign shares an essence with the object.

Similarly, an original instinct is an analog the object it is in reaction to. For some animals, instinctual distress calls and warning signals to the others are analogous to what they represent. They carry the information from the stimulus straight to the response so that other animals can hear them, in order that they may begin to react without having seen the threat.

In first learning communication, a human child must gesture to represent its needs. The child basically has no knowledge that its actions are also communicate information to an adult. The infant simply expresses the internal anguish of hunger or the comfort of satisfaction and security without realizing the other who sees that. These expressions are basically analogous; they have direct connections with the intentions that they represent.

Soon, an infant’s gesturing becomes connected to the perception of the other, the adult. The infant learns know how it must act in order to communicate its intentions to the adult by arousing the compatible response in the adult. This happens perhaps by trial and error similar to operant conditioning. But this takes what was originally analogous representations of intentions and inner states, and transforms them into symbols which are shared between adult and infant.

Because analogs are based on the experience of what they represent, they are limited by the experience. We cannot represent something by analogy that we cannot directly perceive. For us to communicate more complex information we must go beyond analogy to convey what is not directly conveyable.

In development, this comes from the child’s communication moving from simple analogous representation to an agreed-upon symbolic level of communication. Only certain gestures work on mom so we must negotiate and take on some of her side of the communication.

Gestures and Symbol

Where gestures sit on the spectrum between symbol and analogy is very ambiguous. As soon as a child learns that crying does not get it what it wants, it must adjust its gesturing according to the symbolic system between the parent and child: a negotiation or an agreed upon language of communication. We typically think of body language to directly represent an inner emotional state or attitude, but body language also gets much of its expression from the negotiations that we learned to communicate our intentions with. There is almost no way of parsing out what is an original analog and what is adjusted to meet the symbolic structure of communicating is one’s society.

Some of the more practical elements of gestures may be what is left from the original analog. For instance, the expressions of rage typically increase the nostril width and breathing for practical reasons but those are also outward appearances that create gestures. Some of the natural ways we express anger may be in some ways still active, but anger is expressed symbolically through the early negotiation with parents and the agreement with cultural and group norms. That occurs more than outright expression of anger.

So what makes symbols so different from the analogies?

Symbols

To convey more abstract things, or things which cannot be communicated via gesture, we must use a system which contains an infinite source of “gestures”: language. If there is something which needs labelling or explaining, all it takes is a cultural agreement among the users of the symbolic language as to what gestures and words mean.

The symbols themselves have no necessary connection to the object they represent, but their meaning comes from the mass of all the other symbols in the language. Without the rest of language most symbols would be disconnected and meaningless.

Imagine if a dog had an infinite number of toys that could symbolize anything that the dog may wish to communicate to the person. Each toy would require an arbitrary meaning based on an agreement between the dog and its trainer. That is similar to how a child may learn the symbolic structure of a society, first making agreements with the parents, then with a wider society. Like the hypothetical dog, language for us is simply the objective perceptions we create to communicate intentions, we just have infinite options, only limited to what culture accepts and what people can agree with. They have no connection to what they represent besides the consensus of the society we are born into.

Meaninglessness of Symbols

The symbolic structure itself is a rather foreign agent in relation to our experiences. But the symbols can still have meaning beyond their isolated definition within the symbolic structure.

A well-known thought experiment which accidentally demonstrates the difference between symbol and analogy is the “Chinese Room” experiment. It tells of an English-speaker in a room in which he receives an input of messages in Chinese, and applies them to a large manual to create the proper output. From the outside, the room seems like an apparently conscious being that interacts intelligently with the world. But the whole time, the man inside does not have any idea what the Chinese symbols mean.

The man doesn’t know the language because he only knows the structure of the symbolic system. He may understand perfectly the relationships between symbols, but not their relationships with his own experience. It would be like learning a new word from the dictionary but finding that its definition contains several more words that you do not understand. Imagine this going on infinitely. You would never quite have a grasp; you would be lost in the abstract structure.

Even if the man in the Chinese room memorized the manual, the man may even, upon leaving the room, communicate perfectly and rationally (in writing), but he may still not even know how to connect it to experiences. Only after experiencing the language in conjunction with life, will he connect the symbols to his own experiences.

Those new words you learn seem foreign until you start hearing them and speaking them for a consensus in the culture. Learning the usage and connotations of words is what allows you to integrate them into the meaningful network of your experience.

A psychologist who deals mainly with autistic children, Stanley Greenspan, tells us that one of the characteristics of autism is the disconnection between symbols and their experiential and emotional meanings. It may be like having all the words and symbols you know become as if you had just recently looked them up in a dictionary. The relationships between symbols have meaning only within themselves, they are never applied to how one experiences them of feels about them. Those vocabulary words that you learn in school never sink in right away until you hear people use them in their emotional contexts. That is the same in the case of the social symptoms of autism like in the perception of subtle gestures that signal for continued social interaction. Meaning does not flow from the symbolic structure alone, no matter how well you may have studied it.

“Our current theory of autism is that its basis lies in the biological problems that interfere with the children’s ability to make this connection; that is, naturally hooking up the affect system to their sequencing system (motor planning), as well as emerging symbols. This is why the child who has some motor skills or has some ability to repeat words she hears begins rote and repetitive actions or words.”

Stanley Greenspan and Stuart Shanker in The First Idea

Meaning in Symbols

We learn our most basic language through emotional experiences with our parents. This is where prolonged attentional communications is necessary for development of these cognitive, social skills. This is when the symbols surrounding rejections like “no” become internally emotional. Symbols then gain their more complex emotional definitions.

Symbols which are learned later on, by first learning the definitions, are not completely integrated into an emotional meaning so that they have a sort of surface level meaning, only the denotation is known, but the social context and full meaning is not known. These can only be integrated by attentiveness to their usage and connotation, but also through their connection with other emotionally meaningful things.

In science or other in-depth studies, the jargon may only be understood on a surface level as isolated from emotion and experience. But the chemist may know how a particular reaction fits into the whole scheme of experiences is ubiquitous for all life. And if this abstract chemical theory is connected to something one already finds meaningful, it can have access to integrate itself into one’s experience. The full emotional understanding of abstract theories and symbolic structures allows for deeper, imaginative, perhaps spiritual, understanding of the symbols which otherwise have no meaning for our subjective lives.

Our symbolic representations are foreign and forced on us, we must integrate them to fully define them, understanding the nuances, and from there we can change them, changing the culture. True understanding of the symbolic world requires the integration via meaningful experiences or through analogous representations that can connect it to experience. This is what artists and poets do. On the surface a poet only uses symbols to convey a message, but the meter, rhyme, and the phonetics of the spoken words are meant as an analogy to the deeper feeling of the poem. Poems convey information directly from what they represent by the way the words are structured, not simply the words themselves.