One of the biggest components of what we call the human intellect is the recognition that one’s senses can be deceived—that we are not seeing the whole truth, and that we can find ways of understanding the world beyond what our senses tell us.

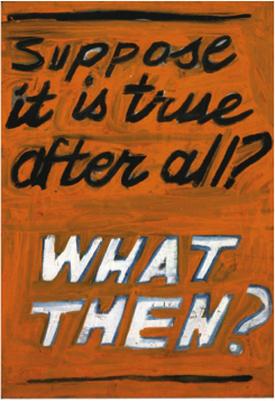

We create truths which deny our immediate senses, whether it is realizing that an emotional, but rare, event is unlikely to reoccur, or discovering the true nature of the Earth orbiting the sun, or if we detect that someone is trying to deceive us for their own benefit. The ability to doubt one’s initial impression is what allows us to become intelligent and reasoning people.

Being able to doubt oneself and reorganize what one believes is an essential skill for the learning mind. But it is complicated by the fact that just because we can doubt does not mean that we can replace our doubts with a better solution. Let’s take a deeper look into how doubting one’s intuitions is a key element in the intellect.

The Original Mind

Before we can understand our self-doubt, we have to know what it is that we doubt. How were we originally seeing the world before we could doubt it?

The mind before doubts is uncritical and relies on the raw experience. In Thinking, Fast and Slow, Daniel Kahneman says that the base system of thinking for us is based on the subtle idea that “what you see is all there is.” We always have some inherent trust in our experience; even if we know it to be wrong, there must be something right about the experience. “The sun also rises,” even when we know that it is the turning earth that is causing the apparent rising of the sun.

Our mind, despite all intellect, will trust part of the senses and intuition and will associate occurrences together. We will always only see the book and not the molecules that we know make it up. In most cases our intellect does not affect this basic associative and perceiving mind.

In some sense, this can get us to an honest idea of the world. If something does not affect our senses, we will not be too ignorant to deny its existence—we would only interact with what is practical. Pragmatically, most people’s lives would be the same if we believed the sun orbited the earth. That is of course false, but it does not matter for the “animal mind” that has its concerns more on the immediate problems.

Where these hidden truths that come from doubting the senses become important is when we look into our long-term security. We do not know intuitively about how things affect our long-term health. So, if we were to rely totally on intuition, we may pick up habits of nutrition and exercise that would put our long-term health at risk. Without immediate feedback through associative mechanism, we wouldn’t understand that our diet is causing long-term health problems. To look into nutrition as a science is to doubt what it appears to us. We doubt so that we can understand the future meaning of some event.

Need to Understand Beyond the Senses

Epicureanism claims that what the body finds pleasure in is good. Today, this proposition is highly misunderstood. Epicureans require someone to have heightened sensitivity to the outcomes of pleasure actually can tell us what is good for our bodies. This is a philosophy that recommends being hyper-aware of subtle senses. If we were to listen to our body close enough, we would know what too many sweets is and that a life of pleasure alone is unfulfilling. Epicureans think that the body knows the best, but we need to listen to it, that it is those theories that will actually get in the way of the actual change one experiences. Perhaps some we can know what is good for our bodies from a sensitivity to what gives us energy and we feel better about shortly after eating something. And perhaps our intuitions about food can be fairly good, but when raised on a strange and artificial diet, we man need the support of the “hidden truths” of nutrition to unlearn certain intuitions.

Taking the long view tells us that we ought to look further past what comes to our senses. In the long-run, understanding beyond the senses is important to prepare for and predict events. It sets us up with a theory of what is going on beyond appearances. With a theory we can predict how things will shake out and how we can act now to give us the best possible outcome later.

Referring to the example of taking care of one’s health, we may have no intuitive reason to believe eating certain foods lead to health problems. What feels good is what we have a tendency to continue doing. But we have been deceived by the pleasure of some artificial foods. Although our body craves the added sugars, it is not what our theory on nutrition says. There is conflict between sensation, which is present, and theory, which considers the future.

But in many more cases, the world is deceptive. If the world were not deceptive, we would not need an intellect or higher consciousness to help inform us. Everything good would feel good and everything bad would feel bad, and there would be no need to dig deeper. Especially in our social world, we are surrounded by deceptions.

“This art of dissimulation reaches its peak in man: here deception, flattery, lying and cheating, talking behind the backs of others, keeping up appearances, living in borrowed splendor, donning masks, the shroud of convention, playacting before others and before oneself—in short, the continual fluttering around the flame of vanity is so much the rule and law that virtually nothing is as incomprehensible as how an honest and pure drive to truth could have arisen among men.”

Friedrich Nietzsche in On Truth and Untruth

It is a Nietzschean idea that our intellect is what allows us to detect dissimulation or deceitfulness in nature, ourselves, and others. So, the intellect stems from the doubt of appearances.

Doubt: Truth Seeking or Myth Debunking?

Although deeper analysis, thinking, and doubting of the senses can give us a deeper understanding of the world, it can also be even more deceptive. Any fact or idea, no matter how truthful, can then be refuted as a deception. We always have the option to look deeper into a situation, and discover “what is really going on.”

Many times, the mode in which we explain things is tied together with some major themes, creating a grander theory about the world. The ideas and theories that we create which we use to explain dissimulation in the world are what Nietzsche calls “true world theories.” Religions and political movements have true world theories which characterize the group’s understanding of the world. We also have these schemas for how we are positioned in the world, as our self-definition.

We shall find that Nietzsche warns us to be aware of these the way we doubt our experience so that it coheres to a theory we already believe. When we doubt so much, we act as if our experiences are myths to be debunked. But we explain them away according to a limited theory. How are these theories manifested in our usual lives?

True World Theories

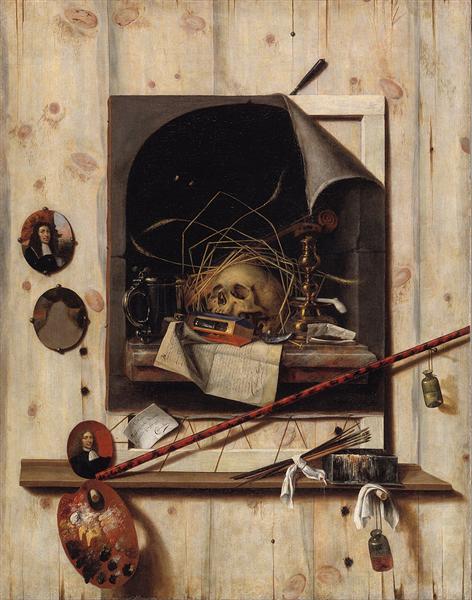

Our “true world theories” are exemplified in one of western philosophies most well-known metaphors. In Plato’s allegory of the cave, it is the shadows that are the mere appearance derived from the “reality” of the fire and the puppets casting the shadows. What we think makes up those puppets and what is going on outside this cave is our true world theory.

In fact, truer worlds are created from philosophy, religion, and science. All claim of invisible forces at work which we cannot encounter with our ordinary senses. They also symbolize a purer world, perhaps of pure facts, rationality, or morality. Science is likely to use instruments, measurements, analysis, and records to uncover unintuitive facts. Religion may use traditions or highly moral people as their method to experience a truer world. These true world theories can also create honorable goals for us to strive towards. William James believed in the practicality of that.

“[Religion is] the belief that there is an unseen order, and that our supreme good lies in harmoniously adjusting ourselves thereto.”

William James

“True world theories” or “unseen orders” run the risk of hiding us from our ordinary experiences. They are the basis for our interpretations, an organized screen between us and a chaotic, ever-changing environment. Therefore, it can be selectively leaving out important information or limiting our self-expression.

Nietzsche refutes this focus on true world theories. He thinks that we create these hidden “truths” to escape from the apparent world. We pretend the more interesting part of reality is elsewhere, we submit to another world as if the apparent one is not worthy of our engagement, and we treat the apparent world as impure and that there is another world which is more real and pure. It would be easy to resign to the evils of today if you had a theory about a pleasant afterlife. For Nietzsche, these are life denying theories.

Although, doubting the senses and intuitions is a mark of the intellect, that does not mean one who doubts the senses is automatically intelligent in a full sense. We often deny the senses for the sake of other intuitions. For a conspiracy theorist, he denies the explicit event for the intuition that there is a secret power behind it. It is parallel to a religious fascination. He doubts because he hopes for a new reality.

Our Relationship to Reality

Our desire for truth is a sort of lie detection for dissimulation of other people’s true motives. In a sense, when we seek to understand nature, we seek to uncover the secrets that it is hiding, like an enemy would be hiding a secret. What is curiosity but treating our senses as an enemy? It is observing something and then looking for more beyond the initial experience.

Our intellect is based on our relationship to an imagined reality. A disgust towards consequences or complexity may cause someone to rely on intuition. But a fear or denial or humanness may lead one to a focus on the forces which govern reality from behind the scenes. When we doubt our intuitive side, we posit to ourselves that there is a “truer” world beyond our senses. For the truer world to cohere to our basic organization of the world, it must be somehow desirable.

Some sort of reality presents itself to us through our senses. With some skepticism of the senses, we interpret this though organized schemas which are created by tools such as language and science to give it greater truth. But this interpretation can always be doubted, just like the senses can be. When we doubt the organization of our thoughts, we look for further complexity. And in this complexity, we run the risk of being overwhelmed if we do not select a narrative to believe. We cannot continue doubting the organization of our reality. We must eventually settle on a conclusion so that we may make our way in the world.

How do we accept our intuition and senses but be able to doubt them? When do we stop seeking a more complex truth? Perhaps it like trusting a child’s account; she will give her best interpretation of what happens, but we understand, even in its accuracy it is still naively put. I don’t think we can call it a deceptive lie, but we can still doubt it and add complexity to the account. There may be subjective truth in every moment, but there is another truth in how we interpret it with some doubt and the intellect.

Buddhism attracts the true world thinker. Westerners go to Buddhism to know Enlightenment or with hopes that they can begin to see a “truer world.” Often this comes from a mistrust or dissatisfaction with the perceived world. Someone seeking Enlightenment seeks to escape the sensed world. But we do not become Enlightened by escaping our senses. The Buddhist tradition is very aware of this as a problem, or as an obstacle to Enlightenment. It is not about the true world in which we experience Enlightenment, but the ordinary one, the present one. We cannot be Enlightened while also hoping for another world.

“A student asks his master, ‘How do I attain enlightenment?’ The master asks, ‘Have you finished your rice?’ ‘Yes,’ replies the student. ‘Then,’ responds the teacher, ‘wash your bowl.’”

Jeremy Safran in Buddhism and Psychoanalysis

If magic is the result of mechanisms which go on beyond our senses then what we might aim to experience is the “ordinary magic” of experience. Experience has a richness is the way that we perceive it without interpreting it through a lens of a “truer world” by doubting its validity. Even deceptions contain a truth, and “truths” contain deceptions.