Why do we have so many negative emotions? Why, when we get angry or sad, do we want to avoid the anger or sadness rather than deal with it directly? Our general pessimistic or optimistic outlook on life goes beyond the following essay—to a discussion of the self perhaps. Putting aside the idiosyncratic lens we see the world, there is still some negativity in most emotions. Anger, sadness, anxiety, and fear come to mind as emotions before any of the so-called pleasant emotions like joy or happiness, both of which are vaguely defined and are questionable in their status as actual emotions. So what is it about emotions that makes so many of them leave a bad taste in the mouth?

This is not because people are born as unhappy pessimists. The negativity is just one of the qualities of emotion. To be emotional is to want change, to be motivated, and the urge to do something is not usually a feeling of content. Emotion puts strain on the body to act, the acting feels good, but the emotion itself can be uncomfortable. Even joy strains us, for it is to want even more, to continue whatever gave you that joy, forever perhaps.

Taxonomy of Emotions

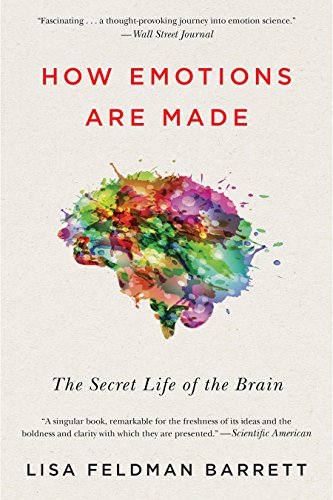

Emotion is so elusive in its taxonomy, that any attempts at categorizing them have been only for pragmatic reasons—not reasons of any natural divisions in emotions. Although some emotions have a unique biological character, it is not essential to the emotion. We all cope and suppress emotions differently. Anger for some people can be so covered up that it is hardly recognizable in neuroscience as anger. In her book criticizing how we have previously categorized emotions, Lisa Feldman Barrett says “variability is the norm.”

Another way of categorizing emotion is to describe generally the situation that provokes it and the actions which it evokes. This not only is a good way to think about emotions practically in our lives, but it can also show why the physiological characteristics of emotions are typically the way they are. Although fear can present itself in many ways chemically, it is usually the situation which gives it its name.

The reason why the situation and biological markers of an emotion concept can line up nicely is that, when given a general situation which requires particular action, the body prepares to act. Thus we feel emotion in addition to perceiving it. The physiology reflects the situation and the actions necessary for dealing with it. Fear is often dealt with by fleeing the object, so it should come as no surprise that that the typical physiological markers of fear allow for a quick escape.

Emotions Start with a Goal

To categorize emotion in a way that makes sense practically and physiologically, we must start with a crude theory. Keith Oatley is an advocate for the idea that all emotion comes from a change in the status of seeking a goal. It is a controversial idea and has obvious objections, but we can work around them and see the value of the general theory.

“[E]motions occur when a psychological tendency is arrested or when a smoothly flowing action is interrupted.”

Keith Oatley

The most obvious example is the anger and frustration. We feel when an obstacle comes into our path—when something stops our “smoothly flowing action.” When someone cuts you off on the road, you become angry, not only because your goal of travel is interrupted but also your goal of self-importance.

But the obvious objection is, “what do we make of positive emotions?” Where Oatley calls emotion a response to interruption, I will adjust it—making the claim all the more vague—to merely a response to a change in a goal status. As mentioned earlier, joy can be at perceiving an imminent success of a goal. This is perhaps why we cannot remain happy without effort. To experience joy is to get closer to something, not to be static in life. That is the first take-home lesson of the theory: we cannot maintain emotion for the sake of itself, something must change in seeking a goal.

Expectation and Striving

Striving for something is not normally considered an emotion but it does have a feeling of want associated with it. It is neither good nor bad, and most of these emotions are neither good nor bad. They become bad when acting upon them has negative consequences, but the emotions themselves are mere tendencies and suggestions. We can be uncomfortable with our anger because it hurts our relationships, or we can love it because it can be a source of vigor, excitement, and power. Other self-conscious, moral judgements—called meta-emotions—are what add characteristics and complexity to these basic emotions.

A critical component of emotion is to first be seeking. We have a desire or goal which we want to accomplish. And because we want it, we also in some way, conscious or unconscious, expect that we can achieve it. Seeking the ideal romantic partner is obviously impossible, for there is no ideal human. Yet many of us continue to expect that to be a possibility even when we have been married to the same imperfect person for many years. Sometimes we expect too much and it causes problems.

We all know that we feel much greater anger when we are closer to a desired object. We expect to achieve it soon, but when something interrupts us, we become furious. A field experiment done by M.B. Harris demonstrated that people’s anger was greater when someone cut them when they were near the front of a line than when they had just gotten in the line. We have higher expectations near the front. Our goal is disrupted while we had great expectations for accomplishing it.

Alain de Botton knows this and recommends to people who are chronically angry that they have a healthy dose of pessimism, or lowered expectations.

“The greatest part of our suffering is brought about by our hopes (for health, happiness and success). Therefore, the kindest thing we can do for ourselves is to recognise that our griefs are not incidental or passing, but a fundamental aspect of existence which will only get worse – until the worst of all happens.”

Categorizing Emotion Using the Goal Status

To give us the best categorization of emotion, we can consider the situation in regard to seeking a goal. This can give us a category that will generally contain similar physiological characteristics. The physiology of an emotion is going to have a great deal to do with the desired action that the situation asks of us.

I say this theory is crude because I do not think that it is a natural or essential division of emotions which we have imprinted on our DNA. I do think it has pragmatic value in how we go about looking at our emotions. Emotions are extremely complex. In theory we can come up with an emotion for any situation. For instance, there is a Japanese emotion concept which is defined by a very specific situation that Lisa Barrett describes in her book How Emotions Are Made.

“‘Arigata-meiwaku’ is felt when someone has done you a favor that you didn’t want from them, and which may have caused difficulty to you, but you’re required to be grateful anyway.”

But if we decide upon some general categories for emotion, we can align those situations with something in our DNA, that can also apply to any specific emotion. By this categorization we may better be able to understand the origins of our emotions, and how they relate to our goals. Our self-consciousness and sociality really complicate things and give us complex emotions like jealousy, pride, loneliness, and arigata-meiwaku. But underneath there may be a few general situations to help us understand. But remember “variability is the norm.”

Four Basic Emotion Pathways

To start off, we have a seeking desire, something that we want. And the most obvious outcome would be to achieve this desire. This is the seeking pathway of emotion, and its subcategory of consummation. We desire something and feel that emotion, and when we get it, we enjoy having it. The leftover cake from the party is something you might desire all day, your behavior when you get out of work, speed down the road, avoiding tedious errands is seeking behavior. And each successful moment of it has some positivity. You enjoy getting closer to your goal.

But that is not what happens, ever. There are many swerves of emotion along the way. Traffic is terrible as usual, but it still pisses you off. You consider extreme measures like driving off the road, running a red light. What you are feeling is in the rage family of emotions. Obstacles which you can or have to overcome impede you on your goal striving and you plan to get by them somehow.

As you are thinking about your lovely cake you realize that it is over a week old. The thoughts of how sick you got last time you ate old cake comes to mind, and you are hesitant but decide to eat it anyways. You have just overcome the fear-anxiety pathway. That there is an obstacle that might hurt you in a way that you cannot overcome. This time you decided you will take the risk, that you could, in fact, overcome it.

You come home, and you find that your husband has already eaten the last of the cake, and you really wanted that cake and not some other equally delicious dessert. That cake was special, you were attached. After anger at your husband you feel sad. And object that you sought and were attached to is no more, you are in the panic-anxiety pathway. You grieve the loss of your cake.

Conclusion

For us to learn from our emotions, we must be able to understand what they are trying to tell us. A general way of conceptualizing emotion is a good start because it can help you to start thinking about some complex or vague feelings you might have in a situation.

For instance, if we are unreasonably mad at someone we love, we can ask ourselves what is it that they are interfering with that we want the to stop so badly. It is our desire to be treated like someone who is independent? Is it that proving that they are not the (unrealistic) ideal person we desire who knows exactly what we are thinking all the time? Is it a jealousy that your loved on keeps you from feeling significant because he or she spends so much time on his or her passions or hobbies? Even complex emotions can be broken down into these groups and they can help us to figure out more about ourselves than we think possible.

Perhaps this can even get us closer to the path of our true desires and tell us the actions that might take us to where we want to be.