It is difficult to understand what is left of our animal instincts. Are they underneath somewhere operating in the unconscious? Are they practically gone, overthrown by culture or cognition and freedom? They play a clear role in the survival of other animals, but it is not clear what is left of them in humans.

Understanding the transition from instinct to emotional decision-making requires reconceptualizing our adaptive behaviors as having elements of prediction and preparation in them. Evolution equipped us with instincts and reflexes that seem to predict a great deal of problems we will inevitably encounter. Similarly, the habits we’ve developed are the result of past experience, predicting future experiences by assuming that the future will be like the past. But what about the decisions we make consciously; how are they predictive? Those are clearly predictions, by judging hypothetical alternatives to an action, you have to be predicting outcomes. What is new to this mode of action that is different from the others?

The Moving Organism

“The nervous system does not invent behavior, but it expands it dramatically.”

Maturana & Varela in The Tree of Knowledge

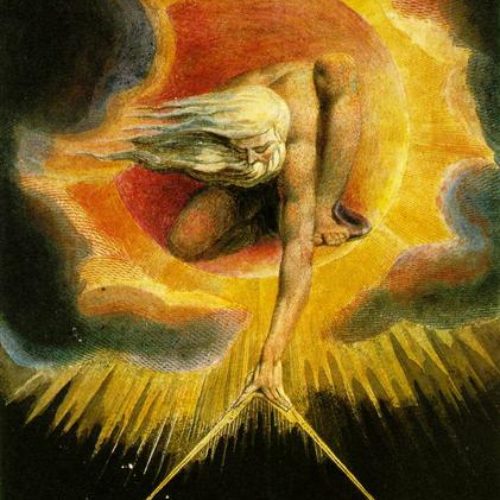

To get an idea of what it’s like to be a moving, feeling, emotion-based animal, we may have to start with what is basic to being an animal at all. Let’s imagine the most basic organism as it is moves about seeking nourishment and reflexively reacting to threats and opportunities. We can imagine this as a bacterium living a short life in a relatively simple environment. As the creature evolves, and the local environment changes, it develops new and more complex mechanisms of existing. Still unaware of its movements, it makes due merely by mechanical and chemical operations, however complex the actions may seem. The organism does not know why it does what it does, nor does it know the ends which it apparently seeks. The organism, if it knows anything, it is the repulsion of a toxin or the pleasant satiation of consuming nutritious substances. But “knowing” here does not have a clear definition. How is knowing different from responding?

The behaviorists would claim that this is where development stopped, and there are no magic steps that human accomplished that goes beyond the realm of more and more complex behaviors and responses. But something different clearly exists. No other animal can hesitate before acting, think and have a sudden idea about what it will do. For instance, dogs will try just about everything to get food off the counter, but almost never sit and think to bring a chair over to get up.

The Need for Greater Complexity

When the environment gets more complicated, harboring diverse threats and the body expanding its requirements for survival, there is a need for greater complexity of reactions and abilities. Even in a very complex organism there can be examples of reflex-like behaviors. Take, for example, the over generalization of some instincts towards danger as seen in deer. “Like a deer in the headlights” is a phrase noting the maladaptive freezing response deer have to the headlights of a car. Because deer have not evolved with an instinct for dealing with blinding, 60 mph chunks of metal hurling towards them, they use the same response that they would for any other potential predator: freeze to remain unseen. In this example we can see that instincts have a somewhat narrow utility and sometimes cannot be adapted to more complex situations. The solidity of the response is actually maladaptive.

Theoretically we could have an animal continually develop instincts and reflexes, making them more and more complicated. Just give the deer the programming to move quickly out of the way as it sees headlight. That would be a simple solution, that perhaps time and selection pressure could make happen.

But we can take this to its natural conclusion and say what if that’s all human life is? We are all extremely complex programs for dealing with environments. There is no need for consciousness and it may only be a byproduct of this web of reflexes. From this idea, philosophers have dubbed the term of philosophical zombie. A “zombie” is a hypothetical person who acts in every way like a human but is non-conscious, like an extremely well programed robot. But this is only hypothetical, and it demonstrates the miracle that consciousness is.

Simply adding complexity to instincts is not the solution to our survival. An environment or situation requiring the development of adaptive behavior will not tolerate simple thoughtless actions. Therefore, it would be a disaster to simply continue adding more and more complex instincts, and apparently it was for early humans.

“As organismic and social complexity increased in more advanced species, it was not possible for each new adaptational demand to be solved by development of a new reflex, so more flexible, context-sensitive response mechanisms evolved.”

Richard Lazarus in Emotion & Adaptation

A New Solution

What does this “flexible, context-sensitive response mechanism” entail?

We might want to rush in and say that big step in human evolution was to accommodate more contextual information! But I want to slow down and observe how instincts can already be quite context dependent. Instincts are by no means simple; they take into account so many biological and homeostatic factors. Even what we think of as the simple knee jerk reflexes can be shown to require many other factors to allow for the reflex. Kurt Goldstein, in The Organism, discusses how all reflexes are far more contingent on context, and bodily positions. So, it would be conceivable that adding more and more reflexes could summate to a highly context-sensitive response mechanism.

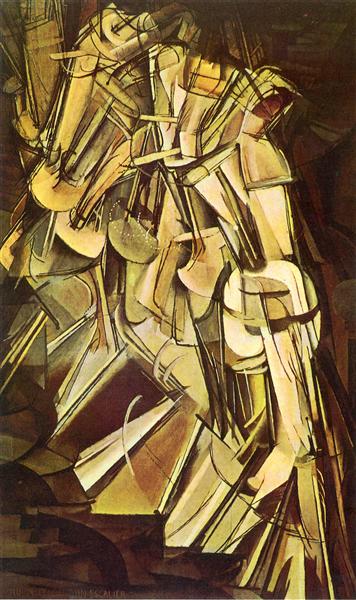

Let’s imagine that is what happened with the human brain. What happens when an animal gets more and more complex action mechanisms that are at least somewhat flexible and context-dependent? In the presence of a complex situation some of these action mechanisms conflict or contradict with each other, creating a tension to be resolved.

“The animal that exhibits [contradictory instincts] loses the ‘instinctive’ demeanor and appears to lead a life of hesitation and choice, an intellectual life; not, however, because he has no instincts—rather because he has so many that they block each other’s path.”

William James in Psychology: The Briefer Course

I think William James is right that with the growing complexity of possible responses, we have allowed a period for hesitation and thought that can appreciate how complex a problem really is.

It may go without saying that an uninhibited action would not be blocked by a competing instinct; it would go on as action. That means that we can still act instinctively but when instincts conflict with each other, it opens a period of hesitation. In the moment of hesitation, we can are still influenced by the context-dependent drives that are competing to get us to act, but options are still being considered, and their influence certainly still has a part to play.

Prediction and Preparedness

Rather than an instinct always committing us to an action, if contradicted by another instinct, the instinct will set the body only into a preparation for that action, and other instincts can continue to be taken into account. In moments of action readiness, that is where instinct still exists in human beings.

Lisa Feldman Barrett, throughout How Emotions Are Made, shows us how emotions are predictions and preparations especially regarding the change in hormone release and energy budgeting. According to Barrett, what we know as the feeling that accompanies emotion is the preparation for action by budgeting bodily resources.

Something that may cause an inkling of action may now only prepare you, bodily and in thought, for whatever may need dealing with. We have moments here of deliberating, and this is what we experience as the intelligence of an emotion. But the perception and thinking operates within the framework of the action preparations we still define the world through the eyes of the instinct or habit when we hesitate to think.

Perception Is the New Action

The way we see the world stays within the bounds of action. It contains a whole way of seeing the world, just as the instinctive action is a way of seeing the world in terms of action as well. But in this case, we represent things as abstract concepts, not merely things-to-be-acted-upon. The headlights to the deer are a representation of threat which should elicit a freezing response when encountered. Action tendency and perception and representation are inherently tied up.

Representation is adding the organization between the stimulus and response. There is a reciprocity between stimulus and response, Jean Piaget says “the input, the stimulus, is filtered through a structure that consists of the action-schemes . . . which in turn are modified and enriched when the subject’s behavioral repertoire is accommodated to the demands of reality.”

We use those “action-schemes” as ways of seeing the world. And since there are many motivated ways of seeing the world, we have several action schemes for any single object, allowing us to abstract out object as “neutral” in definition. Needless to say, this opens up a wide world of cognition and emotion that we can deal with later. For now, we can appreciate that conflicting instincts (or action programs or habits, or whatever the name) has give rise to a large amount of adaptability to complex and diverse situations.