We know fear quite well. It is always one of the first to come to mind if we are asked to name emotions. Fear is an emotion we encounter to some extent on a daily basis. But what is fear, and how does it fit into the other affect programs that have been discussed in other articles? Although FEAR, as an affect program, raises some interesting problems, it can be well-understood within the context of the other emotions.

The other emotional affect programs, which are innate, neurobiological systems that may be considered the core of emotion, are not exactly emotion themselves. FEAR (in all capital letters) is one of them which induces particular responses to objects that are threatening in which fleeing to protection or freezing or avoidance are some of the best options. But it is not exactly what we call fear, the emotion, although it is at the core of the emotion. Just like how we do not consider SEEKING an emotion, but it lies at the center of many related emotions.

Today, we may not find FEAR to play a central role in or lives, because the conditions which originally caused fear are rare (predators, violence, etc.), but FEAR is often present as the source of avoidance behaviors that plague a modern society’s willingness to take important risks. It is the comparison of fear to the other affect programs, particularly SEEKING, that we can learn how to better utilize fear rather than let it control us.

What is the FEAR Affect Program?

When discussing the RAGE system, we learned that RAGE is a reaction to a threat to oneself, one’s values, or one’s goals that is dealt with by destroying or deterring the threat. FEAR is similar. However, its appraisal is that, instead of deterring or injuring the threat, the best thing to do is avoid it, to flee to safety, or in dire circumstances, freeze to avoid being seen. Another possible response similar to retreating to safety is seeking social comfort and protection, which makes one’s early relationship with parents one of the most pivotal determination of one’s fear sensitivity.

If the response repertoire is inherent in us, some of the stimuli which we respond to is also inherent. Fear-objects seem to have an innateness that is unlearned rather than learned. This biological preparedness is evolution’s way of suggesting, rather wisely, that there are some things in which you want to assume are dangerous before you assume they are inert. It is better to mistake a stick for a snake, rather than mistake a snake for a stick.

“Without a FEAR response (along with the learning it promotes) homo sapiens would not have optimal abilities to escape and avoid dangerous situations and to carefully monitor the safety of their environments.”

(Montag & Panksepp in “Primary Emotional Systems and Personality”

This is the classic notion of FEAR, but what is its relation to the SEEKING system? After all, I have claimed that all emotion is derived from SEEKING and goal status. FEAR seems to be the most difficult to explain in this way.

Fear and Its Relation to SEEKING

Instead of claiming FEAR depends on SEEKING, I will discuss how FEAR is always implicit in SEEKING. In other words, we can experience FEAR without striving to a goal, but striving to a goal under normal conditions contains an element of FEAR or hesitation.

What might first be noted is that almost all things that we SEEK are full of potential dangers. If we hunt, or forage, we must risk the unknown world. If we make a friend or find a romantic partner, we are made vulnerable and risk being betrayed. If we play with others, we risk injury. Where there is great opportunity there is also the highest competition. In the jungle, the watering hole is a necessity that also incurs the greatest risk, for predators know to lurk there. From an evolutionary perspective, there is no question that reward often lays in the realm of danger.

From our modern experience, those two do not have to be inextricably tied; after all, much of what we seek in terms of nourishments are safely available. There would be absolutely nothing to fear when it comes to getting our essential needs met. But even the most innocuous objects still have an element of danger if we abandon the fear of the consequence of seeking them.

In cases of Kluver-Bucy syndrome, a condition characterized by fearlessness, we can see the role of fear that is apparent in all seeking activities. Kluver-Bucy patients often become hypersexual and highly exploratory in sexual activities.

“These patients (and animals) also become hyperoral. They indiscriminately explore objects by mouth and sometimes attempt to eat inedible objects. In addition, they display a symptom called hypermetamorphosis—which means that they become hyperdistractible, as everything seems to be of equal interest to them.”

Solms & Turnbull in The Brain and the Inner World

It becomes apparent that some FEAR may be essential to tamping the exploratory pathways to keep them sensible. A lack of fear is similar to cases of people who have the strange disorder of painlessness, which might seem enviable, but almost inevitably leads to a short life due to reckless behavior. Fear and seeking and exploration have a tight relationship. FEAR tames the SEEKING pathway. It keeps us from going too far from home. It can also be used to make better decisions and plan more for the possible outcomes of exploration.

SEEKING Enhances FEAR Learning

In fear learning research, it appears that inducing SEEKING behavior and expectation of reward can increase the general attentional span or curiosity of an animal to see new stimuli as novel. However, a necessary side effect of that is that, while seeking, one is more likely to learn the association of fear-objects, even those objects that were once familiar.

So perhaps the curiosity and adventurousness required to successfully complete one’s goals has the added sensitivity to associating cues with fear responses. When in a SEEKING mode, we may not be ultra-vigilant, but if a danger presents itself, we will not forget what cues might have led to that danger.

When we seek, we also learn to anticipate the dangers. We have reservations even about the things that we want. That is a core tenant of the psychoanalytic perspective where these two affects are tied up, suggesting that there is no reward without a threat of punishment. They might suggest that there may be threateningness as well as the desirability to anything one wants.

“Anxiety is linked to internal drive, in fact the drive satisfaction would be associated by the child with an external danger. For example, in the anxiety of castration, the sexual desire directed towards the mother is threatened by the castration of the child’s penis. The drive investment that generates anxiety must be repressed, revoked and neutralized by the ego.”

Di Costanzo Salvatore in “Neuropsychodynamic of Anxiety”

Goals, Fear, and Preparation

As in the last article on RAGE, I concluded with how we can change the ways that we perceive our goals to affect the RAGE system. Here, I want to do the same with FEAR. One way to look at your curiosity and goal-striving is that of taking the fact that FEAR is inherent in any SEEKING enterprise. Even the goal itself is, to some extent, feared, as psychoanalyst may discover.

This FEAR in response to SEEKING can come in two important packages: something you merely feel afraid of, without a goal, or a goal that you are afraid to pursue.

One cannot really know what one wants without fear. You may know a few things, but many goals are cast aside because they have been deemed impossible. If we take seriously the idea that FEAR is likely to result only from wanting and valuing, we must take our fears seriously. It should be a daily exercise to see what you fear and what reward lies behind it. Try and define that reward—it has been neglected. What purpose would fear have if you did not think at some point you should have to encounter it? The fear is hiding something you might need to encounter, and preparations are needed to encounter it. Where you feel threatened reveals that there is something you value being threatened. Constantly remind yourself of what it is that you fear; the rewards behind them are easy to be blind to.

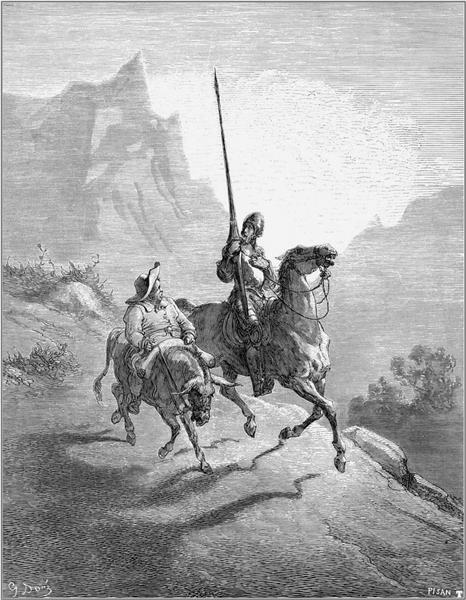

Another way to consider this fear-seeking relationship is in something you know you want, but the goal is lofty, and you are taught to not want too much because it is dangerous to “fly too high.” You fear the obstacles that may come from striving. But to stop in your tracks as soon as you realize the dangers of your goals, means that you give into fear. If your goals are tamped down by fear, they remain pipe dreams. But to ignore fear while striving towards a lofty goal just as foolish. No matter how deleterious you think fear is, there are still dangers in any venture.

What this means is using fear to prepare for battle is the proper attitude. Take risks, but be prepared to take them. Stanley Kubrick reflects on this notion in his D.W. Griffith award acceptance speech on the lesson with the myth of Icarus. The lesson is to not reject fear, but use it.

What makes this attitude even more vital, is the point made earlier about our ability to learn fear responses more readily when SEEKING. If you seek a lofty goal, without preparation, failure will lead to greater fears in the next attempt. Seek wisely. Prepare to take risks so that you do not become averse to the goal. Small risks allow you to enter into the domain of success without as much tumult. Treat yourself as a phobia patient would be treated in exposure therapy.