Mental imagery requires perception. We cannot think of something if it has never been represented in something perceivable. We think via the track that memories of what an object has presented itself to us as. Sometimes it is the memory of its sight, or sometimes it is a word that represents it. Some concepts that we use as tools for thinking have never been directly perceived, yet we still have the ability to think about them because we have the language to represent it. These concepts are abstractions.

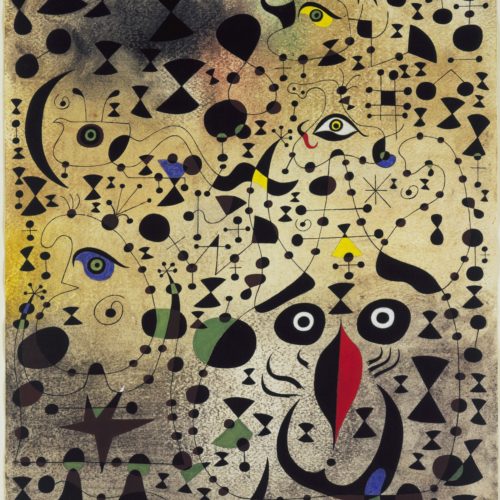

Language can identify, and make objective, the things which are not necessarily perceptible—phenomena which, without the accompanying word, we would have a hard time even discovering the specific boundaries that the word might entail. This is the advantage of language. To give names to things which are not directly perceptible is to abstract. We’ve heard the word abstract and think of the head-in-the-clouds reasoning or the meaningless shapes and splatters of paint on a canvas. But we do not think of “abstracting” as something that we do every day.

Defining Abstraction

An abstract word is something that does not represent something that is directly perceivable or even representable through some simpler means of imagery or definition. Abstract language is something that takes a little more time to understand because it has no direct connection to our experience. This is what abstract language becomes, but how do we get to it?

Just being a symbol to something imperceptible is not the full definition of abstract. This definition does not explain how we have come to accept these abstract things as a part of reality—how they do end up connecting to our experience. It seems we would just be able to make anything up and have a rather clumsy language. Sometimes that can become the case, but for the most part, abstract language comes from experience in a less direct way.

“What is associated now with one thing and now with another tends to become dissociated from either, and to grow into an object of abstract contemplation by the mind”

William James

To abstract is to find similarities between two things, and create a concept for what has made those two things similar. The element that is similar is taken out of the whole experience and becomes an abstract object on its own.

At its very core, abstraction is pattern recognition. An abstract word is the name of a pattern without the perception.

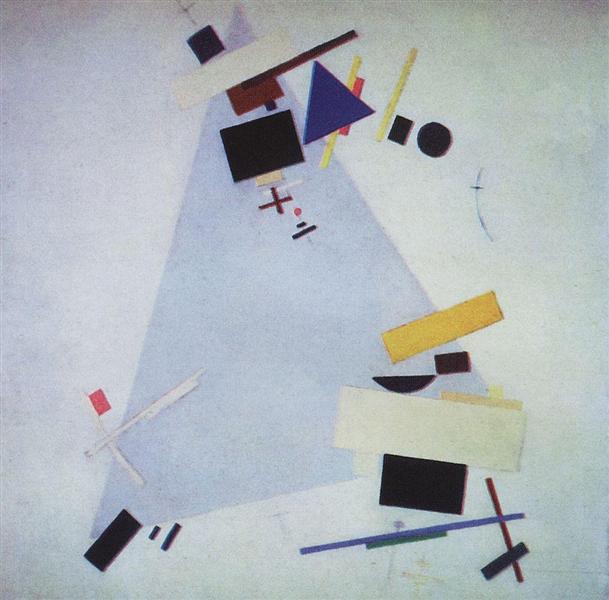

Ways of Abstraction

Our abstractions make up a large portion of language. There are many different ways of abstracting, and here are a few.

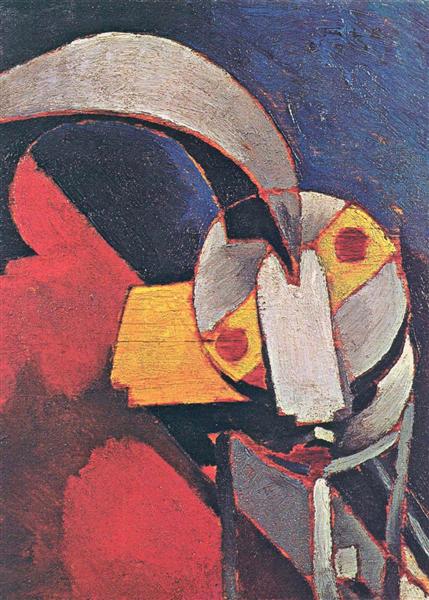

Abstracting Features by Resemblance

Features and qualities of something are actually an abstraction from the original object. For instance, we can imagine “roundness,” but it is never without a perceivable object that we can imagine it. We see that two very different objects still have something in common. What they have in common we create an abstract word for. It is “roundness” that makes the moon similar to a soccer ball.

You may think that you can see “roundness” but you can only see that something is round, not that there is something called roundness that is a quality of something. The difference is subtle. Basically, all features, when given the language are made abstract and represent some imperceptible quality. Even color. If you are to look at a red block, you are not seeing red itself, you are seeing the object, which has the abstract quality we call “redness.”

Parts: Similarity by Synthesis-Function

Similarly, we can look at a total object and discriminate what some parts of the object do for whole. We can see that the motor in a car has the same function as a motor in a lawn mower. We can even claim that, as many biology teachers do, that mitochondria are the motors of a cell. “Motor” is not a word defined by the perception but by its abstract function in relation to a whole object. It is what converts chemical into movement—an abstract idea.

This type of abstraction is what many scientists manipulate in experiments. Say, if we remove a motor, how does it affect the whole car? Or if we add more of a chemical to the body, how does it affect the overall health? The abstraction is in the function of the variable part that is being manipulated.

What is implied here is not a similarity in perceived qualities but in the function a part has to the whole object. A citizen is a word not just to define a person, but is abstracted as a part of the higher concept of civilization.

Creating a Wider Perception

Which brings us to an opposite form of abstraction: defining a whole system that many parts contribute to. Sometimes it is a part of an object that we see, and it is the whole pattern that we must recognize. Long-term patterns which can only be known unconsciously without language, now can be given a name.

For instance, William James uses the example of “climate.” We can perceive the weather in the moment, but to have the concept of “climate” means that one must track the accumulation of weather over a long period of time. This way we can see large scale patterns that we would have never noticed without the larger concept.

Necessity of Tools

The last example brings us to the next point on abstractions. We require tools to create abstractions. With climate, we must be able to record the weather in many locations for at least several years to get any idea of what “climate” means. This is impossible for any individual to do with memory and intuition. We require the instruments to measure (barometer, rain gauge, wind vain) and the tools (paper, ideas) to record and conceptualize what those measures mean.

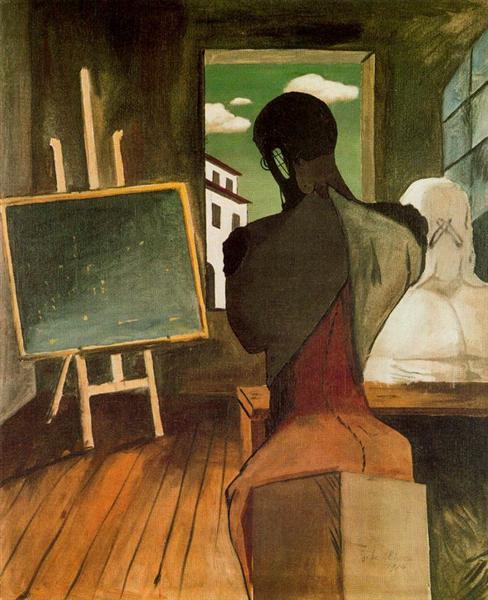

The best tools are things that can represent the abstraction in an analogous way. That is why graphs are so important to have in scientific works. A graph of climate records hits much closer to our perception that reading the individual data points. Being able to use metaphor or create an image that better defines an abstract idea is the most important part in fully understanding ideas. Whereas the abstract word requires continual usage to be understood well enough. That is why art and poetry is so interesting. They attempt to define abstract ideas, which may not even have names, into some image which is directly perceptible. We may consider art and poetry as tool for perceiving the depths of our psychology.

Our most used tool for abstracting is language and definition. It is language that allows us to have explicit memories to recall long-term patterns. What is both good and problematic about language is that it is handed down to us from civilization. This is great for those who cannot ever hope to discover everything on their own. The problem is that when we are born into a culture which contain inaccurate, useless, or even harmful abstract ideas.

A Faith in Language

Sometimes we get too far in the abstract to really be able to tell if concepts are accurate or not. We have built conceptual houses on faulty foundations. We may have taken abstract ideas for granted because they were given to us by someone we trusted. We lose the cultural context in the way some abstractions were created and we simply accept them as truth and build further into abstraction. We also may have built our own ideas into these abstractions and have been on the wrong path ever since.

When we are given abstract rules and ideas, sometimes they insert themselves into reality on their own. A highly accepted abstraction may have no basis in reality but will seem like it because of how well accepted it is in a society or subculture. Naming something asserts that there is something essential about the distinction.

People often accuse some philosophy of going too far into the abstract. This makes sense because it is a domain that uses instruments that are purely conceptual and has been developed over a long period of history. Giles Deleuze called philosophy the creative invention of concepts. The tools for building these concepts is language and its logic. Over time, ideas have been built upon ideas. Although it is important to base one’s philosophy off of those who have come before, it is important to reexamine the tools we use to get us these concepts to see if the concepts hold any weight. Those tools can help us to go further into understanding our lives, but at the same time restrict our idea of reality.

” [Cultures] are restrictive in that they impose upon individuals born into them an already fixed-system of signification. . . But cultures are also liberating because paradoxically they provide the textual resources by which individuals can seek new meanings on their own.”

Marcel Danesi in Messages, Signs, Meanings

Whenever we accept an abstract concept, we are accepting that it has some real basis in reality and that it was created from an honest and pragmatic look at the world. This requires faith. Just as the scientist has faith in her instrument to detect the measures she wishes to record, a person in a culture has to have faith that the ideas represented in symbols measure reality in a pragmatic way.

But the faith has to be complemented with the deep thinking on the subject. We must be able to use our language deliberately enough to give other people the abstract tools for their thinking without so much misunderstanding. The unwarranted faith in language comes from accepting what has come before as substantial, without reflecting. And we will not be able to monitor how much people reflect on what their culture gives them, but we can do our best to give people a reason to have faith in language, but having conversations which thicken the meanings of our language and give it honesty and truth, that most people can have faith in, while others can still reflect upon.