Giles Deleuze defines a philosopher as a creator of concepts. The philosopher creates ideas which help us to understand and act effectively and meaningfully in our lives. The philosopher may not only create new concepts from nearly nothing but he or she may expand and bring nuance to existing ones. Adjusting and solidifying the meaning of language becomes an entryway into a very elusive truth. The equipment we use to find these truths is that of language.

In another article, we have also talked about “tools of inquiry” as setting up situations to see how they play out and drawing inferences about an invisible reality according to the interaction. A microscope uses a setup of lenses to allow smaller things to reveal themselves by extending into our visual capabilities. That smaller reality reveals itself in its interaction with the microscope. Another tool is taking records and writing things down; in that way, we can then see long-term patterns with greater accuracy.

Language is one of these tools as well, but it is not clear how it fits into the grouping, yet it is certainly one of the main sources of our worldly understanding. Language does reveal a reality to us, the reality which comes from reasoning. Let’s reconsider the philosopher or the user of logic. Like we set up a drop of pond water under a microscope to allow it to reveal itself, a philosopher puts concepts into a situation where their definitions can be challenged or improved upon in conscious ways. Thought experiments seem to be a tool like this, but instead of the world deciding the result, it is logic and definition which teach us something.

Philosophers play with ideas and situations that analyze our concepts. They use logic and reason within these situations in order to reveals some deeper truth. This means that the denotations and defining is something that reveals to us more about the world that we could not sense before.

Let’s take a step back to understand this concept.

Solidifying the World of Ideas

We create and fortify a world of ideal representations from our past experience. But rather than just a mental copy of something, an idea is more of a habit of perceiving and interpreting. The world of representations is only relevant when something present is being interpreted. We are able to change how we react to things by changing the idea of them, and therefore, changing the interpretation of a possible situation.

Here, we can see the truth in Plato’s theory of forms. He draws the distinction between a world that is visible and one that is intelligible. The visible is what we experience through the senses, and the intelligible is the ideas we have about our experience that we can use to think about it. It is our mental representation that helps define a concept that gives us that ability to know about something that at one time was only visible. What is visible ispresent, and how we have learned to interpret what was present is intelligible. What is intelligible is what is abstracted into the realm of reason and logic. It is in playing with how we abstract that we can inquire about how the world functions underneath what is visible.

When you add to this language and our ability to strictly define our language, we can create a tool for navigating ideas. When we give representations and ideas strict definition, we can use them like any other tool of inquiry to understand the hidden elements of our world.

Mental Manipulation

We can test the relationship between baking soda and vinegar by mixing them together and observing the result. That manipulation results in a gaining of empirical knowledge, and eventually we may be able to conclude something about the chemical reaction. Similarly, we can put concepts together and take them apart to see the result. Rather than testing the relationships out in the real world—for instance, seeing how the microscope changes the look of the pond water for instance—we test out how a perspective for interpretation makes an idea look. Instead of vinegar and baking soda, we combine ideas—perhaps of free will and morality, for example—to understand more.

However, this does not mean, hopefully, that because these ideas do not “exist” in the physical world that they do not abide by any rules. They certainly do not abide by the rules of nature. However they do abide by the rules and structure in which our language defines these things and the logic in which we can use definition to determine relationships. The laws of Nature are replaced by the laws of definition.

It is only through symbolized ideas that we can reason. We use what we have recognized as a pattern, symbolize and define it in a word or concept, and the use rationality to conduct “thought experiments.” Not all great and practical truths will have a physical experiment which reliably confirms it (although, they can support a truth). Sometimes it comes from an exercise in logic that gets us to a practical way of living.

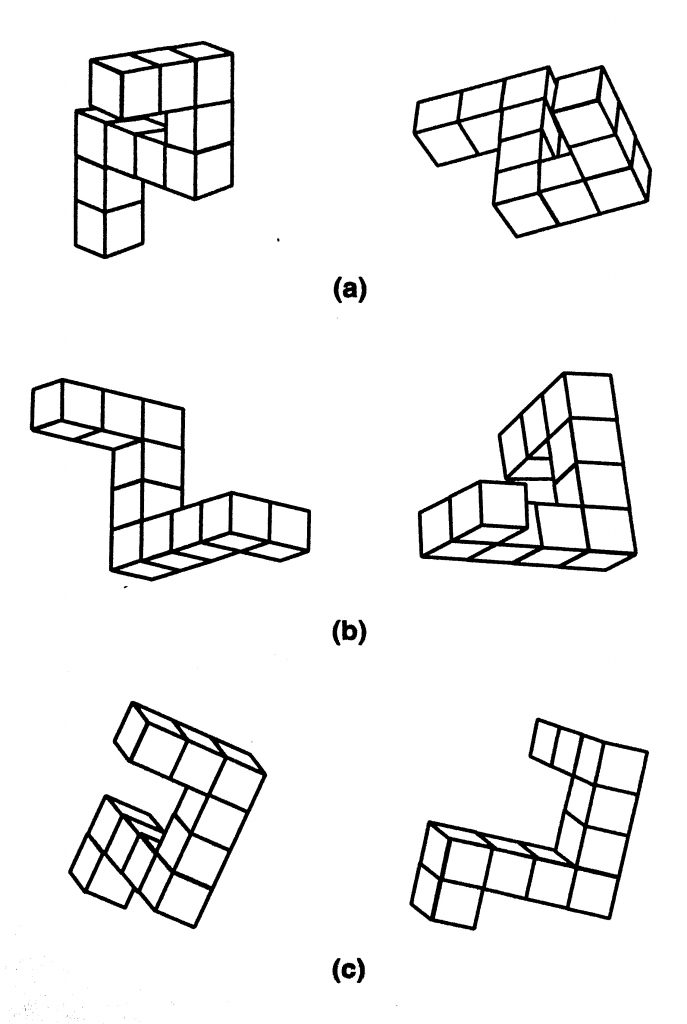

It appears like there is evidence in how we use the rules of logic in a way derived from our experience in the real world. Our thinking (or mental manipulation) of ideas seems to be related to how we might manipulate things in reality. An experiment replicated a few times, shows that the time it takes to mentally rotate an image of an object is correlated to the time it would take to physically rotate the object. This suggests a similarity between the tools of inquiry we manipulate in the world and the tools we manipulate in our minds. In this case, the rules surrounding the idea of the object are reflective of the object if it were obeying the rules of Nature.

Sharpening the Tool of Concept

We know that thought experiments and logic alone cannot supply our total understanding. If we do not have definitions that reflect our collective experiences we will instead be playing with the narrow definitions of our own personal biases, excluding both the experiences of others and the utility of the other tools for inquiry. Only using definitions cannot be the only method towards truth. You may merely be creating imaginary concepts out of imaginary symbols. We may gain an interesting web of theories and ideas, but it will fail to parallel our actual experiences. We must also take other routes towards truth, but we can first refine how we use symbols as a tool, so that, if we are misled by our thinking, we can soon find our way back.

How can this create truth with logic out of what seems to be divorced from reality, completely in the mind of the thinker?

The result of trying to strictly define complex things results in the possibility of having several parallel truths almost equally competing for reality. Any given person, for instance, can have many definitions based on the roles they play. When we ask what a leader is, we conclude that it is someone we follow trusting that they know the way, but it may also be the leader’s purpose to allow us to freely discover our own path. There are many such dichotomies which exist because of our experience, but they often clash as ideas. We have not yet parsed out the functional elements of the words that we use. Thus, the truths we find here will almost always contain much nuance if they are to reflect the diversity of experience.

We tend to prefer catchphrases, folk wisdom, and pithy aphorisms because they can be immediately understood and applied. Slavoj Žižek detests folk wisdom because there is always another aphorism or wise saying which can contrast with another piece of wisdom. For instance, the wisdom of “stay grounded” contrasts with “dream big,” while both can sound deep and meaningful.

I do not detest the phrases only unless they were to be used as the finished answer. The point Žižek makes is that what is a truth also can be applied to other situations and be false. A mere sentence does not contain the truth, but only the elements of truth that have yet to be completely understood.

It is not in pithiness that we find truth, but in understanding. A true statement can only be recognized if its parts are understood. For you to read only these sentences should, if I have done my job right, not be nearly as truthful if you have not read the earlier writing, and the writings of others as well.

For us to be satisfied with any wise-sounding answer is for us to answer “yes” to the question, “can you explain the meaning of life to me?” Our understanding begins with asking questions ceaselessly, and ridding ourselves of the hope that the answers will come in a small repeatable package.

To be competent in using the tools of language and conceptualizing, we must consciously reflect on how we define things from our experience. How do things relate or oppose each other? How can things be alternatively defined. It helps to read the thoughts of others in books to expand definitions to what you may never have taken notice of.

Any answer that may be summarized in a sentence or even a paragraph is only partial. It takes understanding and further questioning to continue on a path towards truth.

“The answer is an embarrassment to the question.”

Marcel Blanchot