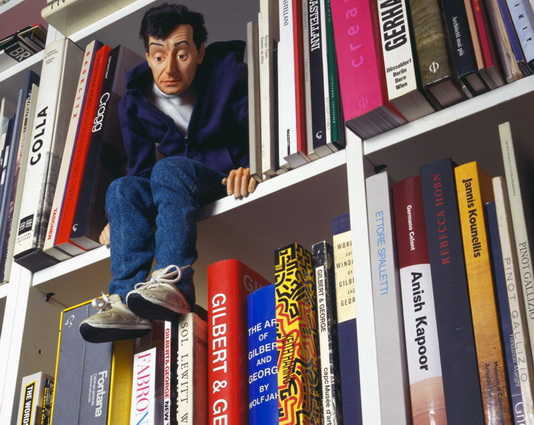

In our lifetimes of education, whether in school or on our own, we contend with the desire to improve our intelligence. We have a tendency to begin by remembering facts, reading up on topics, and learning the vocabulary of an interesting domain. We become a sponge of the symbols in the domain of our interest, but this leaves something out that we have been seeking. How does repeating what others have said before improve our intellect of give us a fuller understanding. We are not very accustomed to recognizing this difference between memorization and intellect, but it can be a meaningful one.

For me, a discussion of what “intellect” is can teach us what is the subtle but important difference between fact-learning and full understanding. We may then learn that the true potential of education is if we can build on more than a database of facts. What can we understand about “intellect” that can tell us what we need to do to improve how we think, not only our domain, but the whole of our lives?

What is the Intellect?

It’s first useful to define what the vague concept of “intellect” is. When we think of intellect, we think of that innate brain power that we are born with. I think it is important to hold on to that notion because it is certainly true that some people are oriented in the world to be more intellectually inclined than others, but that does not mean the exercising the muscle will not give us all the ability we need.

Intellect or intelligence seems to be our ability to think using the strict rules of logic. It is the glue that holds ideas together in a web of causation and interrelatedness. It allows us to run scenarios in our head, predict outcomes, test hypotheses, and find potential errors—all in the private confines of the mind. Thinking uses rules that exist in our symbolic structure. Our symbols define the premises and conclusions of a situation. When those definitions are well-defined for us, we may navigate through the meanings of those ideas. In short, the intellect is what allows us to smoothly hypothesize and test the validity between the many premises of a scenario and the possible conclusions based on the meanings of the ideas involved.

So, the intellect, in its simplest form, is the ability to say, “the cat is on the mat,” and be able to fluently infer that the mat is under the cat or that the cat might like the mat. But a fluent intellect may think of other possibilities and implications of such a proposition.

We carry a large amount of ideas with us to interpret a situation. Every situation is framed according to these ideas. The intellect, as we define it here, is what considers the implications of situations. It is only by these mental definitions that we can create deeper, logical meaning for us to understand situations—both simple and complex.

The Rules and the Facts

Why is the intellect important? In the previous article, it is because it can help us detect a discrepancy between reality and our perceptions or intuitions. We can easily be decieved, but the intellect is what gives us the tools for seeing the world more accurately. The intellect allows us to use rules and ideas to test out the validity of our intuitions.

In Thinking, Fast and Slow, Daniel Kahneman gives us a great example of how rules are necessary to test some things. Perhaps the simplest rule is that of addition. We can intuit immediately which line is longer than the another if they are continuous and side by side. But if the lines are segmented and scattered, we could not say immediately which was longer. We would have to add up the lengths before we made a conclusion. We require a rule to come to an accurate conclusion.

Thinking requires logical rules that are created not with intuition but with tools. Consider how we would teach a child addition: a child may learn addition by counting two groups of items, and then putting them together and count them again.

Lets return to the aspect of education which emphasizes the memorizing of facts and concepts. These are not totally separate from the intellect that I describe. But they are to tools through the intellect flows. Concepts are ideas which contain rules in which the ideas can interact. To know your concepts well in a subject will help you navigate the domain with intelligence.

Full requires the understanding of the rules in which the concepts are applied. Someone who doesn’t know how an organelle contributes to the function of a cell, but has the terms memorized, will only have a superficial understanding of cellular biology. Someone who know a singular function or interaction an organelle has with the total cell may have a slightly better understanding. But an expert understanding in this field requires more complex understandings of the interactions and contributions of a part to the whole and the other parts.

We require the rote memory of vocabulary and concepts for deep understanding. But we know that superficial rehearsal of terminology may only cover for real understanding. We repeat words which have no precise definition in our minds and we understand very little of the consequences of the propositions we make. Some of us do this because we can benefit from the social power of seeming intelligent without the effort of forming a robust intellect.

Understanding is more than a list of the facts. There are many facts about one thing, knowing a few of them can be good, but it makes the intellect narrow and biased. How can we strengthen the ability to navigate through difficult ideas if it is not as easy as repeating the ideas?

Application and Reality

Our problems would be nice if they all came down to simple mathematical equations or basic premise-conclusion pairings. The reason math is so nice is because its symbols have very simple meanings. They mean basically one thing, with few implications. But that is not our reality.

For us to act intelligently we must respect the complexity of our situation yet be able to find the simple part that are most relevant. To train the intellect is to consider the complexity and seemingly infinite number of rules that a concept may contain. This requires effortful reflection on what the consequences of the premises are and what the conclusions may imply. When we simplify a concept, it is not because it is a simple concept but because we have chosen the most relevant element of it.

William James gives the example of paper being more relevant as a writing surface in some situations, but more relevant as a way to start a fire in others. It is the understanding of the many properties of some central concept that allows us have fluid intelligence. And this, as mentioned, comes from using the tools of the intellect to trace out the logical properties of a concept.

“There is no property absolutely essential to any one thing. The same property which figures as the essence of a thing on one occasion becomes a very inessential feature upon another.”

William James

When people have an under-developed intellect, it is often because of the neglect of the other properties of a concept. For these people, one concept has one basic interaction with other things, one essence. It is to think paper can only be burned. These people have never analyzed what the implications of a concept are or if there is a clear meaning to them at all.

It is in these undeveloped intellects that inconsistencies and hypocrisies can arise. The essences of concepts which remain unconsidered will conflict while we remain ignorant of the inconsistency of our thought. From this method of exercising the intellect towards building a complex schema of the world, we can then test our thoughts and others’ by testing their consistency.

“The only test of rationality is not whether a person’s beliefs and preferences are reasonable, but whether they are internally consistent.”

Daniel Kahneman in Thinking, Fast and Slow

The Everyday Philosopher

The mark of a developed intellect is having internal consistency of well-defined rules and concepts. When we consider a new idea, we can immediately apply it to what we know and test its logical validity within our current set of facts.

“The greatest enemy of any one of our truths may be the rest of our truths. Truths have once for all this desperate instinct of self-preservation and of desire to extinguish whatever contradicts them.”

William James in Pragmatism

The long books of philosophy tend to be great examples of how the intellect is exercised. They test every hypothesis and every interpretation and ensure that there is total consistency throughout the whole world or logic that they created. The intellects of these philosophers are robust and are quickly able to discern what does not fit into their philosophy. They come across as opinionated, because they have created their own way of thinking in the world, and it has been made consistent.

For us, what is important in creating a consistent theory of anything is the necessity of self-scrutiny. Not only can this sort our where we are logically inept, but it can make our knowledge our own, rather than someone else’s that we have learned to repeat. Analyze the words you utter, write in a journal, or say to others or to yourself. Is there contradiction with your other beliefs? Remember there are many qualities to any one thing. The habit of this makes us the everyday philosophers.