To us, feeling seems to be the most essential part of emotion. A feeling is the truest instance of embodiment connecting our internal mind to the perception of the external reality. It seems feeling is a secret path towards what is important in the world.

This belief requires some balance. Feelings are not the core of emotion, and we play an active role in the interpretation and perception of feelings. What we may perceive as the core of emotion, is not even a requirement.

“Feeling is the ornamentation of emotion, not its essence.”

Robert C. Solomon in The Passions

Let us begin with the origination of feelings and observe how they seem—and sometimes are—essential. Then we may begin to understand how feelings can be merely an ornamentation. Not only will we understand how emotion works in accordance with feeling, but we will begin to understand what people mean when they unveil the advantages of “mind over body.”

Homeostasis and the Environment

Let’s start with a rather undeniable fact: we are biological creatures which have a structure highly influenced by the need to maintain homeostasis. All action or drives can be thought of as attempts to regain or maintain this balance. Conservation of energy, comfort, avoiding harm or injury, hunger, and immunity all serve to regulate the body’s state.

“All living organisms from the humble amoeba to the human are born with devices designed to solve automatically. No proper reasoning required, the basic problems of life. Those problems are: finding sources of energy; incorporating and transforming energy; maintaining a chemical balance of interior compatible with the life process; maintaining the organism’s structure by repairing its wear and tear; and fending off external agents of disease and physical injury. The single word homeostasis is convenient shorthand for the ensemble of regulations and the resulting state of regulated life.”

Antonio Damasio in Looking for Spinoza

You are probably thinking, “Surely, it cannot be so simple!” And you would be right. It is worth noting that in many situations, our bodies put us out of homeostasis to incentivize action. Threats are an obvious example. The body must react to something external to maintain homeostasis in the future. In a world of prey and predator, the body must be able to predict an injury that it would not be capable of repairing after the fact. There is nothing directly dysregulating in the body about seeing a bear in the woods, but through evolution of threat-detectors, our body can predict when there are external threats to internal homeostasis. The result is a relatively minor change in homeostasis to prevent a much greater one.

Another such example would be sexual activity. Theoretically, a person can live a balanced, homeostatic life without sex. But evolution insists that we not simply exist, but reproduce as well, our body chemistry will throw itself out of homeostasis to get us to go out in the world, risking treats and wasting energy, to reproduce successfully.

These “exceptions to the rule” do a very good job of illustrating the means in which apparently non-homeostatic actions and desires are sought after. This is a broad way of seeing our actions as biological, but from here we can start to understand how our body relates and changes to the external world in a pattern of achieving a homeostasis with its broad definition. Internal homeostasis always relies on what we do in the external world.

“The essence of mental life and of bodily life are one, namely, ‘the adjustment of inner to outer relations.’”

William James in The Principles of Psychology Vol. 1

Drive

To maintain homeostasis the body must be able to detect and interpret the body’s internal conditions. These detections of the internal milieu are transformed into a tendency for action. Our interpretation of them is directly connected to the action which we have been conditioned to do to resolve the imbalance of homeostasis.

It should be noted that our drives towards action are not a simple amalgam of feelings. Often the focus is on one at the expense of all others. We would not be motivated towards sexual activity at the same time were starving, for instance. It would be conflicting and inefficient if all current needs were expressed to us at once. Our nervous system does this calculation internally. Consider how even consuming pain can disappear with the spike of adrenaline that comes with sudden fear. Our bodies can calculate that it is better to risk reversing healing than to be injured more severely.

This calculation comprises our “drive” at any moment in time. If our feelings are derived from these internal conditions, and our brain can automatically do the calculation of which drives are most important, why must we feel them first? Why not link them directly to the action? This may be the case for many animals who have seemingly simple behaviors, but even some of our complex behaviors can be done without consciousness—as we know in our daily activities of balancing walking, talking, and doing seven other things at once. Why does our internal state then become conscious?

Motivation Comes Before Conscious Feeling

We can imagine ourselves moving about in this world precisely as we do already, but without the pain of desires and discomfort. This is perhaps the essence of the philosophical “zombie” where we imagine a person who acts in every way like others, but without any consciousness, without the same nexus of subjectivity that we experience. So, it is not that hard to imagine being capable of doing what we do without the feeling of our internal states.

The catch is that feelings, the perception of the internal milieu and action tendency, are not the same as the action tendency itself. It is true that, in most cases perhaps, these two things line up perfectly. That perfect correlation is why feelings seem redundant. However, there are many cases in which they do not line up.

While we are acting, we are not perceiving the action tendency as feelings; we are acting them out. If we were to stop and reflect, that’s when we would notice the internal milieu as feeling. The moment when we feel, is the moment that we are making a choice. The action tendency, if it is not action itself, is a nudge towards an action, but allowing for other options and interpretations. As we have seen in a previous article, feelings and thinking are actually the separation of stimulus and action.

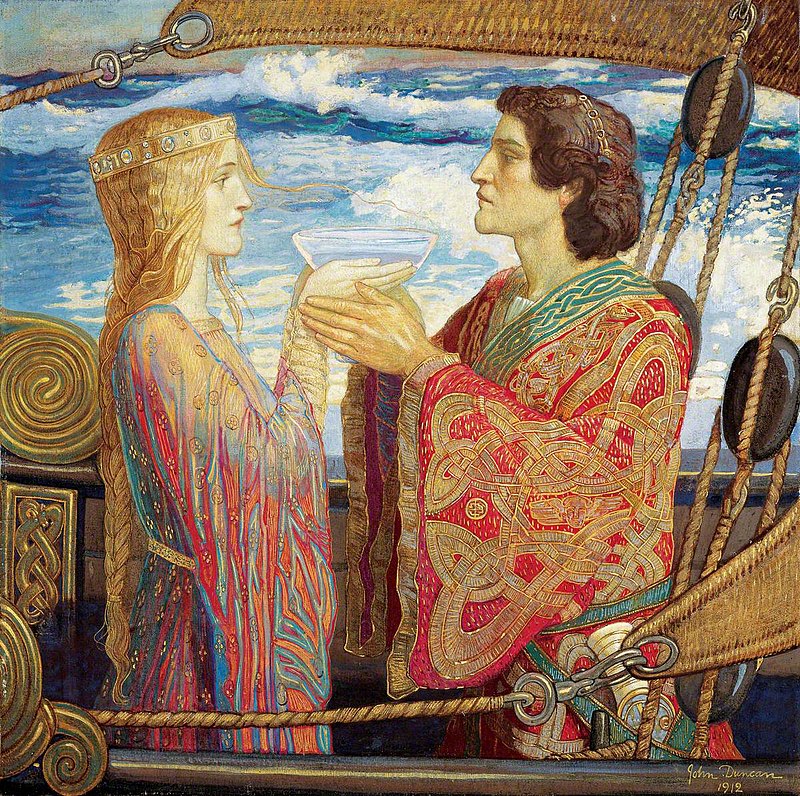

Sometimes, we think of feelings as the cause of action. For instance, it is common to think, “I jumped away from the dog because I felt scared.” However, action, as we mentioned, does not require feelings or consultation with the body; the body simply acts. We can feel when we are not merely acting. It is only after the emergency in which the feelings are consulted for further action.

“We feel sorry because we cry, angry because we strike, afraid because we tremble, and [it is] not that we cry, strike, or tremble, because we are sorry, angry, or fearful, as the case may be”

William James

Since feelings are perceptions of our internal conditions, it should follow that internal conditions or reactions come slightly before the conscious feelings in the causal chain. And this is seen also in careful experimentation. Antonio Damasio shows in his that markers of emotion are detectible by measurement before they are detected by the person as conscious feeling. He concludes, “the changes in skin conductance always preceded the signal that a feeling was being felt.”

“Emotions play out in the theater of the body. Feelings play out in the theater of the mind.”

Antonio Damasio in Looking for Spinoza

Appraisal of Internal Information

Our bodies are adapted to sense things that we may not know as consciously important; therefore, it would behoove us to listen to what our body tells us about a situation. We could not consult reason each time for feeling may know something that we do not about what is the proper action. Feeling of a situation can be thought of as a sixth sense that is overlayed on top of all other perceptions, giving them meaning. But how do we interpret that?

Perceiving “feelings” is not as simple as it sounds. There is no panel on our bellies that tells us the state of our emotions and how to cope with them. To reiterate, these feelings are manifest in a tendency to act. But since action is not independent of the environment, action tendency is a mode of thinking about the environment around us. Feelings are manifested as a mindset that perceives things with certain motivational regard.

“A feeling is the perception of a certain state of the body along with the perception of a certain mode of thinking and of thoughts with certain themes.”

Antonio Damasio in Looking for Spinoza

“The perception of visceral information is registered consciously as feelings of emotion and (via association) as reminiscences, in the form of: ‘I saw that, and it made me feel like this”

Solms & Turnbull in The Brain and the Inner World

This perception is highly culturally mediated. We have all been given a cultural story of how to respond to most situations and feelings. This results in the great diversity of how people live their lives. These interpretations vary in many ways, but one dimension they vary is in the authority we give feelings over our motivation.

Authority of Feelings and Control over Them

Because we sense the internal milieu of our bodies to be our body telling us what it needs without our corrupting, cognitive influence over it, we give some feelings an underserved authority. We think, “I feel hungry, so it would be only self-hurting to not eat.” But even hunger can be deceptive as blood sugar and insulin spikes, and their eventual plummets, cause a feeling of hunger irrespective of actual need. In this way, the motivational effect of feeling is determined by the meaning it has for how we should act. If hunger is thought of without need to eat, it will not have its motivating power. But if the hunger pangs grow, they may finally get through to the mind, as the need to eat.

Hunger is relatively simple to interpret compared to other feelings, but the same principle applies. One popular experiment is described in The Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy:

“Subjects in their study were injected with epinephrine, a stimulant of the sympathetic system. Schacter and Singer found that these subjects tended to interpret the arousal they experienced either as anger or as euphoria, depending on the type of situation they found themselves in.”

Andrea Scarantino & Ronald de Sousa

In his book The Passions, Robert C. Solomon also reflects on a hypothetical experience of how anger can be the unfortunate result of drinking too much coffee and not realizing the effect on one’s attitude that can bring. The point he makes is that it is difficult to relegate anger to “just the coffee” just as it is difficult to justify anger with “irritation.” It turns out that feelings my be too vague to use to explain behaviors without using situational information.

Because a feeling’s manifestation is reliant on the interpretation of a situation, can we reinterpret our world to change those feelings. An appraisal explaining the effect of a feeling as non-motivating undermines the motivational aspect of feeling. Realizing you feel a certain way because of an injection, changes your attitude to how you must act, and therefore changing your emotion.

Mind over Body

If we change the way we think of our tendencies to act, we can change how we perceive feeling. To take from the Buddhist conception of nonreactivity, we can perceive our feelings as non-motivational. Therefore, we experience them without their intensity. No matter how real a feeling is, it can be observed without motivation. Just as we have the inability to justify anger with irritability, we have the ability to diminish the importance of reaction to feelings.

This is what allows people to endure extreme conditions and accomplish great feats of endurance, and this teaches us about the body’s ability to maintain homeostasis internally. In the presence of a stressor, the body will first attempt to change behavior with an intense feeling. But if we simply do not react to the stressor, we teach the body that it has no choice but to endure the stress and maintain homeostasis another way, a way that is also natural, but does not require suffering or pain. This may be the essence of the elusive “mind over body.”

“When there is a real understanding of need, the outward and the inner, then desire is not a torture. Then it has a quite different meaning, a significance far beyond the content of thought and it goes beyond feeling, with its emotions, myths and illusions. With the total understanding of need, not the mere quantity or the quality of it, desire then is a flame and not a torture. Without this flame life itself is lost. It is this flame that burns away the pettiness of its object, the frontiers the fences that have been imposed upon it. Then call it by whatever name you will, love, death, beauty. Then it is there without an end.”

Jiddu Krishnamurti