It is always perplexing to comprehend the ability of the human brain, but it may be even more shocking to realize that it must do all this work in real time. We do not chop through frame-by-frame like a loading video. We can recognize something shown to us for only 50ms. That visual information is somehow received in a meaningful form, even if it lives for only a flash. We are quick in interpreting the world, but how is it possible to get all the information we need on time in order to keep up with the rest of the world?

Part of the answer is be prepared for the stimulus, by predicting ahead of time what is about to happen. We do this in a few different ways, one way is by gathering information about the local situation, but the one I will discuss here is by the means of long-term memory. All of our past experience before a perception will help us experience the present world more fluidly.

We usually think about long-term memory as what memorizes test answers, recalls childhood events, remembers birthdays, etc. But long-term memory, at its most basic, before add on the symbolic complexity of language, is a means of interpreting the present moment from the help of past experience.

Memory Basics

At the very core of memory, we find that it is a way of recognizing that something has happened before. Essentially, to remember something is to perceive something with the experience of perceiving something similar before. This may result in a slightly changed reaction to this thing; perhaps you are no longer surprised or curious about it, or now you become anxious, or now you feel more comforted by being in the presence of this thing. The change in your reaction to the same thing through time, is an indication of a basic form of memory. This is a basic form of memory, that even the simplest form of life can relate to this.

“All that is required is that they should recognize the same experience again. A polyp would be a conceptual thinker if a feeling of ‘Hollo! Thingumbob again!’ ever flitted through its mind.”

William James

At this level an organism experiences something, and with attention or instinct, acts on that experience and that interaction is recorded in memory. The next time the experience occurs the whole process is quicker, there is less need to think, and it becomes a natural reaction. The experience prunes down the important features of the interaction in order to help our quick thinking focus only the most action-informing parts.

Long-term memory is the ease and efficiency at which incoming information travels to get to a useful interpretation or action. Experiences, after having memories of them, trigger neurons which have previously found their outlets in a previous experience. The subsequent neurons fire more readily, while others, which have proven irrelevant, become more inhibited. This implicit memory is a strengthening of the links between stimulus and a specified interpretation or response that can successfully deal with the stimulus.

In this way, we are able to predict our experiences based on the past. The hardware of our brain is designed with the future in mind. Our past experience tells us what we can expect in the future. When we see someone let go of a ball, we expect it will drop because we’ve seen it happen many times before. Our implicit ideas of the basic laws of nature were created from experience.

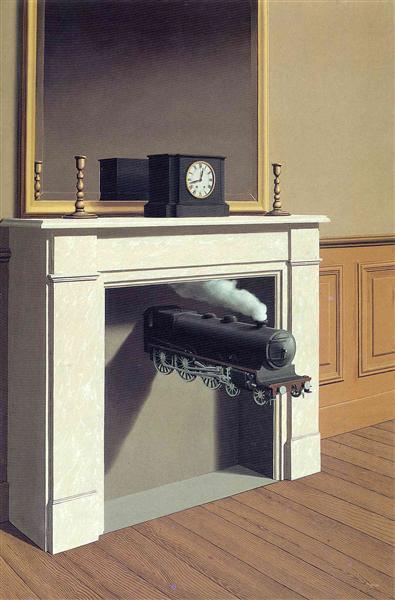

Shock comes from when the experience does not line up with the map of memory. When the ball floats in the air, we are shocked, and we pay close attention until we see what is going on. Attention can correct any errors in our past experience by learning new things, like perhaps the floating ball was filled with helium. Our observation would tell us something new about the world without destroying our whole world-view.

Of course, we are not perfect in the use of this skill. We seem to compromise speed with accuracy. This is something Daniel Kahneman knows very well and describes in Thinking, Fast and Slow.

“Anything that makes it easier for the associative machine to run smoothly will also bias beliefs. A reliable way to make people believe in falsehoods is frequent repetition, because familiarity is not easily distinguished from truth.”

Daniel Kahneman

He distinguishes two systems of thinking, one of them being the fast and experientially-derived one, and the other is more careful and tends to be slower and take more energy to correct the mistakes. Many of what we call biases and heuristics that operate one the basis of experience being recorded into the hardware of the brain.

To sum, long-term memory is a experiential lubricant, like alcohol is a social lubricant. It speeds up the process, but increases likelihood of error.

Intellect Is Cut from the Same Cloth of Memory

Much of how we deal with long-term memory is in explicit recollection. It is not simply the changing behaviors and perception that comes with past experience, but it is also the conjuring of the words to describe those past experiences. With the addition of language, we have a changed mode of memory where we can remember abstractions like dates, facts, and more complex concepts.

The memory structure is what creates concepts for us. But in addition to sending the perceived signal to an interpretation or action, language seems to solidify concepts into a symbolic world. Instead of the intuitive and present concept of home, we can also label it “home,” and the word comes with more associations and definitions than we could have had with just the feeling of home without language.

Since our language adds new pathways in the hardware of our associations that help us predict the future, connecting them to elements of speech, stimuli can now evoke more than an implicit reaction. Now stimuli can result in speech or thoughts that make explicit those past experiences or facts.

Our symbolic world of language now inhabits and adds to the same hardware that the simplest form of learning from experience exists in. Both have these trails of neurons which more readily evoke responses and inhibit others.

When there is a need to recall a memory, the implicit neurons fire, pressuring the words or phrases to come about. When a word in on the tip of the tongue, we experience the feeling of implicit knowledge of the word without the motor or auditory memory linked to it. Language still presents an ability to interact actively with associative stimuli, one thought leading to the next, occasionally bringing the thoughts to explicit language, especially when there is a need for interpersonal communication. This will be discussed in a future article. All we need to conclude is that explicit memory comes from an associative ability that comes from dealings with the past, just like implicit behavior changes.

What Does It Mean to Be Present?

It is practically a given that every moment we inhabit is now. We cannot be in the past or the future; we only can act in the present. But what does it mean to be present? This question is made even more difficult by the fact that our brain is wired from its interaction from the past, and that wiring is in hope to predict the future. There is no escaping the past if you are created from it! And we cannot avoid the future if we are designed to act on its behalf!

We must remember that the present is the carrier of memories. Since we can only exist in the present, the past offers us only the information to act in the present by predicting the present and the future-present. The present is constantly reinterpreting our past memories.

“The knowledge of some other part of the stream, past or future, near or remote, is always mixed in with our knowledge of the present thing.”

William James

Perhaps being more present is to inject more of the present moment into the things which have been constructed by the past. How is this done? The answer was hinted at earlier when I mentioned attention’s role in checking the assumptions our automatic, associative mind makes. Controlling attention is the antidote the parts of us that are made by past experience. To concentrate is to see the world anew, to be affected by the present, and create new paths for stimuli to travel.

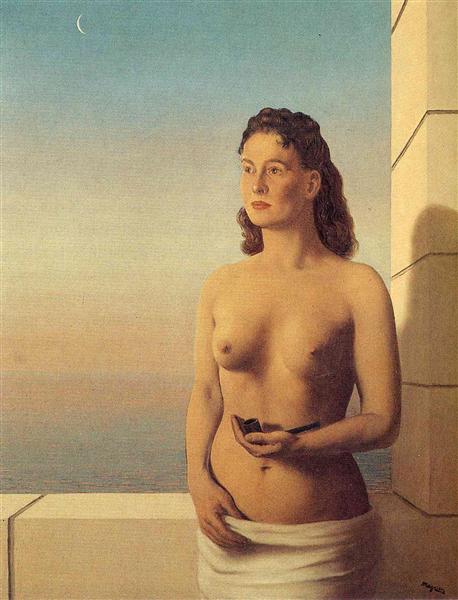

I think what is meant by being present is rather trying to free oneself from the structure that is created from the past. By mindfully seeing the world, we may be able to see what the world was like before our past experience and reestablish the naïve and curious child within us. This of course applies to the thoughts we have as they are also born out of the habitual networks of long-term memory. A concentration on thoughts allow us to more intentionally experience our thoughts thereafter.

What we find is what Buddhism would call the “unconditioned” or the uncaused element of our experience. To explore the unconditioned Zen Buddhists meditate on the question, “What did your face look like before your parents were born?”

In other words, what was there before you could be affected by the world. What was there before you could possibly have a past, a memory. You must have a face of total presence.

We find that many of our self-destructive behaviors and our negative emotionality is caused by some traumatic thought or event that was not our fault, but we must live with nonetheless. To free oneself from the traumatic past without burying it in the subconscious is to rewire it by becoming present to it and giving your mind the opportunity to relearn long-term memories.

Being present in life could be considered a constant state of learning. But not necessarily on an intellectual level, but more of a growth of wisdom.