When we talk about instincts, we refer to innate reactions to innately recognizable stimuli. What is implied here is that there are images and perceptions programmed into our biology. There are some concepts which seem to have, for human beings, innate qualities, as if they were essential to our world.

On the surface, this is no surprise. There are many categories of things that we claim justifies a common reaction. What is beautiful, ugly, pleasurable, or painful all seem to be natural to our biology. Some things elicit a consistent reaction in human beings.

Like a flower must have a natural attraction to a bee, the elements that make up the perception of a flower might have a natural beauty to us.

But at the same time there is reason to be skeptical of what someone calls a universal human good. Many philosophers in the existentialist tradition would deny that there is anything essential about our lives, that we only create values rather than discover them. However, I want to argue that there are some symbolic representations that are natural to humans which can guide our actions and values in ways that are essentially human. I will immediately qualify this: just because there are universals does not mean that they can be all clearly articulated or that we can even know them for certain.

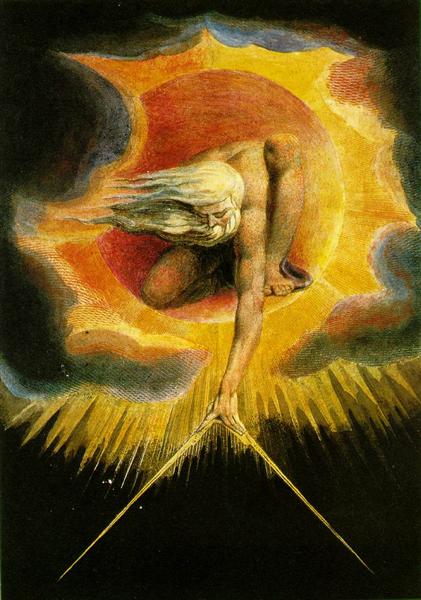

Theory of Archetypes

For us the claim some kind of universal human good in the world, we would have to have programmed in us a recognition of patterns of perceptions. The Danish psychoanalyst Carl Jung theorized about what natural symbols would look like. He predicted this in his spoke of things such as a collective unconscious—a universal set of archetypes which govern our actions—and his work on commonly used symbols. These symbols give an almost spiritual attention to things such as circles (mandalas), caves, stars, mountains, rivers, etc. These natural phenomena seem to symbolize something universal to us; they seem to have element that we naturally recognize and make us feel a certain way. The concepts which we naturally recognize can vary in how easily we can define them. For instance, how can we say exactly what elements of the mountain give us awe?

“Since we live in one world, and each of us is given the same five senses, and each of us has evolved on the same road . . . we all share a universal fund of perceptions. . . concepts that link some object or action of the natural world on the one hand, and our all but preordained response to it on the other.”

Mary Oliver

Some dismiss this theory as unscientific and ungrounded, but we can work it into the other ideas of what instincts are and see how animals display it compared to the complexity of human life. This is where the idea that there are natural perceptions becomes more radical, and harder to imagine. For there to be something universal about some perceptions there must be something about the development of a brain that will recognize certain patterns of stimuli.

Archetypes from the Ground Up

Let’s start with what it means to perceive and react. To perceive means to have something from the outer world come in an affect your behavior, feelings, and/or subjective experience. As we all know, there is a way that physical elements of the world can be detected by our senses and become our experience. Some elements of the world are not detected (i.e., infrared or high frequency sounds); we do not have the apparatuses to sense the physical pattern.

What we detect are fundamental physical properties coalescing together to form something detectable. For instance, the most basic elements of electromagnetic radiation come together to form something that we can detect. That concept of “light waves” seems to have a real effect on us via our senses, and that is innate to all humans with normal vision. Qualities like that are instinctual because they cause a reaction, even only a phenomenological, or experiential, reaction.

Starting from this very basic idea, we can get more complicated. Slightly more complex ideas include painfully wincing at bright lights or a ducking a things flying into the field of vision. These are all things which we mostly assume are natural reflexes that must have been programmed into us a priori. We would have these reactions even before we learned that the object which is growing larger and larger (in the field of vision) was something that was going to smack us in the face. Therefore, there must be some neural patterns which recognize the possibility of these things in the world and produced in us natural responses.

Let’s bring more complex, more uniquely human, instincts into the picture. Psychologists have found some potential evidence of natural symbols using experimental techniques. Studies have shown a certain hip-waist ratio on a woman can be more attractive, presumably because it is an indicatory of fertility or ability to give birth. A savanna landscape seems more beautiful than a jungle landscape, presumably because we evolved in the savannas and feel a bit safer there. Elements of group dynamics, hierarchies, and tribalism seem to be innately recognized. The nonverbals, like body language and tone of voice, seem to give off natural reactions from others despite having never explicitly learned them before. The archetypes of the hero’s journey include a seemingly universal structure of a story which parallels a general human struggle and overcoming.

Experience Versus Archetype

A potential argument against any innate representational patterns, or at least an argument diminishing its significance, is the idea that all of these things are actually learned during life. For instance, the tendency to be dependent on others might seem a natural instinct, but actually it is learned by our former dependence on our parents as children.

Some things which seem innate are actually learned because of a shared human experience, rather than a shared human genome. Simple and complex perceptions could actually just be something learned by experiencing things that are universal to nearly all human experience, for instance, being raised by some caretaker was essential to survive childhood, so archetypes of mothers and fathers are readily formed.

Whether or not it is genetic or a universal experience, there might very well be shared human symbols. Both options give practically same result. Either way seems to be some essential concepts when it comes to our human lives. But how do we define these things?

Defining the Symbols

This is supposed to be about the boundary between the real and the relative. Something relative—the concept of elements which make us a symbol—can indeed affect something which is a real reaction or emotional perception. For there to be naturally programmed symbols means that not all things which appear relative indeed are relative. The sound wave of 261.6 Hz does not necessarily mean an experience of middle C, but because of our apparatus, that is what it is. Just like the attraction of a mountainous landscape or a blossoming flower might evoke an aesthetic experience from a seeming arbitrary perception.

But we still cannot yet say what it is about all these perceptions which make us react the way we do. We still cannot find the raw symbol and place it in a dictionary of universal human symbols because we all have our own history and attitude towards these symbols, and the variability makes it an elusive definition to create. And the more complex we get the more difficult it is to place a finger at the symbol underlying an intuition.

As we can see when looking at the complexity of Jung’s ideas—and at how they did not yet give us the solution—our discovery of the symbolic structures that reside in our minds cannot be defined universally besides in the archetypes of which there are many, and they all function in a chaotic mess. It is no wonder the theory does not hold up to the standards of science; it is a not a question of cause and effect but of putting the pieces together to form the essential symbol. Jung and others do this by looking at anthropology and ancient myths.

“I am large, I contain multitudes.”

Walt Whitman