How does our ability to think abstractly and be motivated by ideal goals create an experience with altered values of perceptions? This layering on top of perception can affect the most intimate parts of who we think we are. Our spiritual self, as William James calls it, is “the entire collection of my states of consciousness, my psychic faculties and dispositions taken concretely. This collection can at any moment become an object to my thought at that moment and awaken emotions like those awakened by any of the other portions of the Me.” The spiritual self is a result of adding meaning to perception and is no less susceptible to fallacy than more superficial parts of ourselves.

This spiritual self is curated by preconceived goals and attitudes that come from an ability to anticipate the future and act accordingly. We talk all the time about how people will see and believe only what is convenient to them, but we rarely look further into what that means and what its implications are on consciousness. A banker may see the ultimate good of money, because it allows him to continue his career in good conscience. That is not a deep statement, but to empathize with this kind of delusion is what can help us contend with our own assumptions.

This is a dilemma that exists in our public and political sphere as well as the sphere of our own personal and spiritual lives and experience, so for that reason it is essential to delve into where our spiritual self comes from. We can see how treating the world according to an ideal goal is a practice which creates the spiritual self, for better or worse.

Equipped for the Future

Any discussion of a self-consciousness requires the discussion of anticipation and fantasies. We can fantasize about and anticipate the future by moving attention to potentialities rather than immediate surroundings. Given the proper motivation our minds can simulate an abstract future from the space of the mind using imagined ideas. This ability is expanded by our language and symbolic representations leading to our ability to play out scenarios with logic and borrowing from the knowledge of others. We are then able to reason and imagine in the ways we are currently familiar with.

To motivate this sort of thinking, we must be motivated by future fantasies and goals, something that cannot be dealt with directly but can be prepared for. Because humans are conditioned in society to be so oriented towards the future, this means that much of our ideas conceptualizing experience is an effect of how we believe they will affect us further down the road, not their present value. This means that nearly all conscious thought, even what seems like natural perceptions, is defined by our preparation for the future, some ideal goal, a fear or fantasy, which may be realistic or idealistic or both. Using this as the framework, we can go forward into how seeing things in this way affects a fundamental way of experiencing life.

If we imagine a situation in which a future goal is intended to be met, and much of our psychic energy is set on completing this goal, we can already see how having abstract goals affects the way one perceives the present world. To a teenage boy with a crush, he sees nothing else; even his friends become ghosts, while he seeks to realize an idealized fantasy. We define our surroundings according to our abstract goals. A craftsperson sees wood in terms of whether she can build a table out of it, while a naturalist may see the species of the tree. But the abstract goal usually isn’t simply to build furniture or recognize species. The end we seek is almost never the objects we use to achieve it; the goal goes much deeper, relating to love, meaning, and self-worth. Perhaps the carpenter learns to see the wood in more detail to finally gain the respect of her colleagues.

You may think this motivation doesn’t matter as long as it is a honorable pursuit, but the motivation changes the manner of the pursuit. Our fantasies that motivate us down a path in life changes the way we frame even the most intellectual pursuits. For instance, a professor may ignore the platitudes of their field because they are not shocking and impressive. The professor may only find importance in the obscure, highly technical things which give them authority when they speak of them.

When in the background of attention is an abstract goal experience gets new meaning based on the path one believes one must take to get there. Some things become wildly important while others are distractions. We have seen people do great, horrific, or strange things in the name of a higher goal. The one similarity between these great and horrible acts is that the doer sees things as a means to an end.

This phrase, “means to an end,” is generally treated in moral psychology as a treatment of someone or thing which is immoral, but I think it is more difficult to avoid than we think. It is almost human nature to treat things with ulterior values. We can do our best to treat people as ends in themselves, but we still see our friends and families through the screen of our needs and fantasies for security and love.

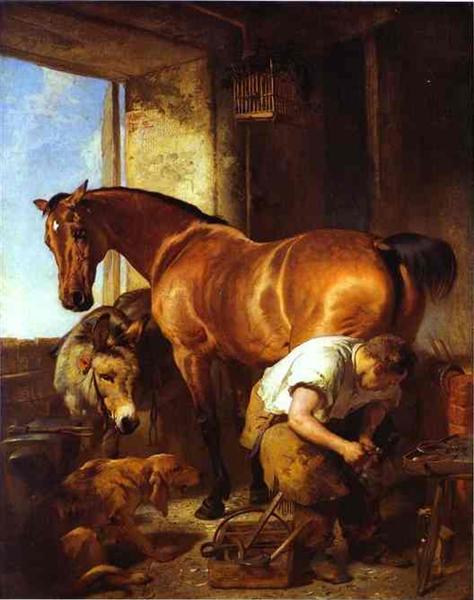

One way to approach the morality of treating things as a means is a path that Martin Heidegger took in his thinking. He saw that as we have begun to see things like means, or like “equipment,” we see ourselves as equipment as well. When we have an abstract goal, and things become emotionally defined as equipment in the pursuit of that goal, we too, become defined by and subordinated for that goal.

“Heidegger claims, not only are the hammer, nails, and work-bench in this way not part of the engaged carpenter’s phenomenal world, neither, in a sense, is the carpenter. The carpenter becomes absorbed in his activity in such a way that he has no awareness of himself as a subject over and against a world of objects.”

Michael Wheeler in “Martin Heidegger” article from Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy

Consciousness (Attention & Thoughts) Become Equipment

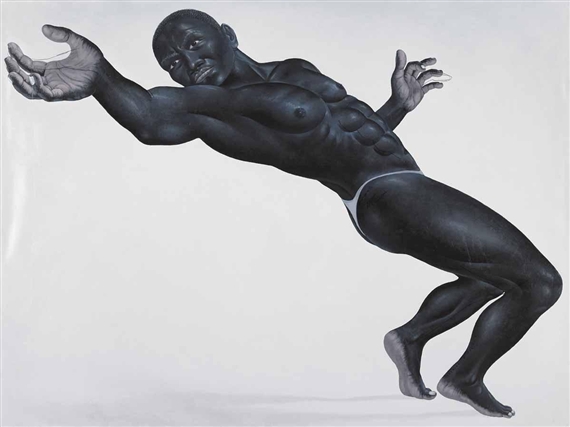

“How we treat the world, is how we treat ourselves.” I have heard some version of this intuitive idea many times, but I didn’t think that it was any more than intuition, a convenient basis for creating a moral standard. But when we see the world through the lens of an abstract goal, we see things as equipment or obstacles, and we become the user of that equipment or the enemy of those obstacles. And the user of tools, is just as narrowly oriented as the tool itself. But even more insidious is that, because of our self-awareness, we can treat our most immediate experiences as equipment. Our consciousness can be treated as tools for another end. Our conscious moments are objects to either support or hurt one’s journey towards a goal. Now, I think we can understand why there may be some validity to that moral platitude.

But this is not simply treating our body a certain way to get something out of it, like putting in the extra effort to hunt for food. Creating the spiritual self is to censor and guide our very own consciousness to support our goals. It even goes deeper to a level like, “how we treat the world, is our treatment of our whole experience.”

No longer can an emotion or experience exist on its own, it exists in a symbolic way with meaning for future goals and desires. To exemplify how a subjective experience can be so easily transformed into a threat to a higher goal, we have an example used in Buddhism:

If you are shot with an arrow, the pain of the wound itself is nothing compared to the pain of knowing “Oh my God, I’ve been shot by an arrow!”

Sara Weber in Buddhism and Psychoanalysis

The pain of being shot with an arrow is nothing compared to the suffering which one feels when they think they should not possibly be allowed to suffer this bodily pain. The suffering is that one wishes oneself to not experience pain, not that the pain itself is the tormentor.

Symbolized Subjectivity

As social animals, humans have been describing our experiences through art and gestures, but language has been a special evolution in being able to convey our subjective experience to others. Being able to communicate our experience means that we are conceptualizing and objectifying many parts of our experience in an effort to convey them to the mind of another. Being able to objectify and package our experience allows us to treat them as having utility towards another goal, a social goal. We want, among other things, to know that our experience can be the same as others’.

We have psychologized so much of our experience, and have given it values as healthy or stable or normal parts of psychology. But doing this, creating judgements is a way of further avoiding present experience. We focus our attention and thought on those things which serve some abstract goal. We try changing our actions, desires, and emotions. We begin to see our sadness, not with value in itself, but as justified or inappropriate, as useless and in the way. With abstract goals, sadness and fatigue become more devastating, self-perpetuating hopelessness in achieving one’s goals, and ultimately resembles depression more than the simple bodily states that so often give rise to moments of sadness.

This can be the most tormenting part, the curse, of self-consciousness. Every moment can be made the object of scrutiny. Every thought can be good or bad. And there is little room to simply just have the thoughts or experience.

One Dimensional Views on Thought

It would be a mistake to say that having future goals is something to avoid striving for because it means that it would transform experience into a means to an end. I believe it is an essential moral imperative that we be able subordinate immediacy for greater goals, not only for the function of society but for ourselves as well, for our future security, health, and well-being. Willpower is to use one’s motivations to do something that will be better for us, against our natural tendencies. It is a clear benefit not only in a society like ours, but in terms of survival and thriving, as in the expert chimpanzee hunters mentioned another article.

But to do this is often to make ourselves into equipment, impairing our connection with our subjective realities. The problem is not that we treat experiences like equipment, but that we only treat experiences like equipment, and particularly equipment with a very narrow range of ability. With a single dimensional goal, we will see only one angle on things.

“To the man with a hammer, every problem looks like a nail.”

A natural result of single-dimensional goals is a polarizing tendency of viewing the world. Much of ourselves in our subjectivity is not neutral. Every thought and feeling has potential for being relevant to our future lives, every conscious moment can be thought of as either helping or hurting our hopes of reaching an abstract goal. We can only have so much consciousness to have, so we try so hard to always aim it at our goals, and it torments us when we get distracted. It is opening up beyond a singular point of view that can remedy this polarity.

But we cannot cheat and make our goal to be a well-rounded human. First of all, few people can have such a fantasy that will be honestly pursued, ulterior motives will taint the quest. Even so, we cannot define a well-rounded human without uncovering infinite paths to be taken, which no single person can take.

Perhaps, instead, the remedy for this is a practice of perceiving without judgement at innate perfection in things. To see something as it is without judgement, is to see from the point of view of the universe, and treating what is as what must be, as perfect. Heidegger noticed that not perceiving things neutrally, and only using them is what has gotten us into this mess.

The less we just stare at the hammer-thing, and the more we seize hold of it and use it, the more primordial does our relationship to it become . . . as equipment”

Martin Heidegger

Like the repeating of a word to force its meaning to disappear into its natural sounds, we can focus attention to lose the equipment-ness of perception. We can also simply be. In Buddhism, the meditation practice is to just sit, with no goals. This gets you into the mode of being that does not treat experiences with the values that we have assigned them. Your thoughts simply bubble up and disappear.

The opposite of creating meaning from ideal goals is to experience “naturalness.”

“It is rather difficult to explain, but naturalness is, I think, some feeling of being independent from everything, or some activity which is based on nothingness. Something which comes out of nothingness is naturalness, like a seed or plant coming out of the ground. The seed has no idea of being some particular plant, but it has its own form and is in perfect harmony with the ground, with its surroundings.”

Suzuki Roshi in Zen Mind, Beginner’s Mind