If we want to create a theory of truth or a method of reaching truth, we must be able to define it with our own subjectivity in mind. What good would it be to accumulate only the most objective facts without any way of applying them to one’s life? There are infinite facts in the world, but should we define truth as whatever accounts for all these facts, or is there something more to truth than the totality of facts?

“If you’re purely after facts, please buy yourself the phone directory of Manhattan. It has four million correct facts. But it doesn’t illuminate.”

Werner Herzog

People often have a problem with allowing subjectivity into the definition of truth. It appears to give people the freedom to distort facts to their own liking. Allowing for people to project their feelings and intuitions onto any scientific fact can certainly results in delusion. Truth is distorted by our biases as we think of our world as we wish it to be, not how it actually is.

What I believe needs to be added to the definition of truth, outside of the traditional objective definition, is the notion of understanding. Truth cannot be understood in any way outside of subjective experience. Thus, we must consider the subjectivity in our definition of truth. But how can we acknowledge the inevitable subjectivity of truth without the cost of major biases?

Truth Requires a Perceiver

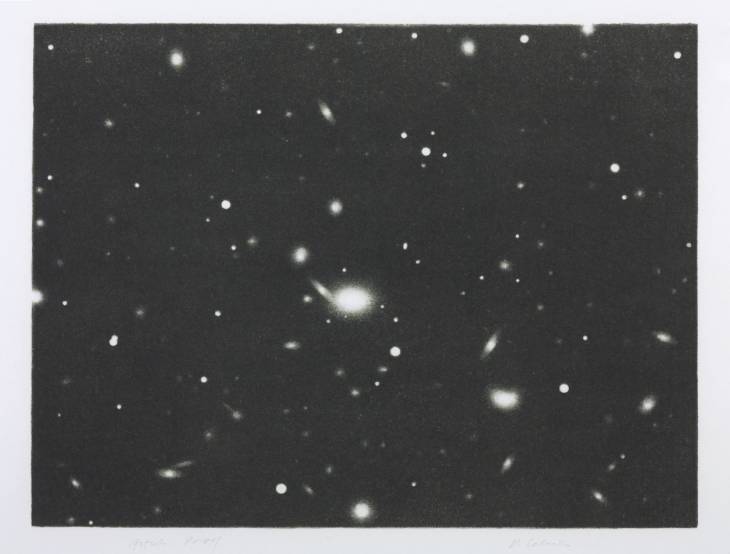

Imagine the result if we removed subjectivity from any claim of truth. We would have only an infinite list of the most mundane data points of what momentarily is. This is the idea of absolute reality. But what would this reality mean if nothing could perceive it, nothing to exist in some point in time. Would everything occur at once? Would there even need to be divisions of what is, or would it just be? What is left of “truth” if there is no one to experience it?

“There were eternities in which [knowledge] did not exist, and when it has vanished once again, it will have left nothing in its wake. For the human intellect has no further task beyond human life.”

Nietzsche

I have discussed our intellect, our fact-seeking part of the brain, as motivated by the using of ideas to accomplish long-term goals. For a human definition of truth, we know that reality does not become truth until there are truth’s pragmatic users to experience it.

Whatever we call truth or fact comes either from the senses, from mental tools we use for inquiry, or from the faith of some authority. No matter how we frame a truth, it will always come from a subjective element which gives the truth its personal importance or reliability. The way we receive information is not neutral. We must have faith in our senses or intuition or the authority of the person or object that tells us a fact. It is the testing of facts along a rigorous notion of subjective experience that makes an objective fact understood. From this we learn how we know something, if we can even claim that we do know it.

“Don’t agree. Find out.”

Jiddu Krishnamurti

For us to find out the truth for ourselves is no small task. We have to question our beliefs and let go of what we have become accustomed to. For understanding, we have to perceive and pay attention to the subjective interface we have with reality.

The Surface of Truth

“All roads lead to Rome, and in the end and eventually, all true processes must lead to the face of directly verifying sensible experiences somewhere, which somebody’s ideas have copied.”

William James in Pragmatism

What is left of the truth if one removes the objectivity? What is left but our actions and perceptions, without ideas of a truer world. Objectivity only lives in our ideas. We use objective ideas to plan ahead and anticipate things beyond what our normal senses and intuition can tell us. But without any notion of an objective reality “out there,” we would live only presently. Things would have meaning only in how they affect us. We do not simply know a fact but we are actively interacting with the world in which knowing that fact is another fact itself.

“We do not see the “space” of the world; we live our field of vision. We do not see the “colors” of the world; we live our chromatic space.”

Maturana & Varela in The Tree of Knowledge

This is the pragmatic route. That our truths require elements of perceptibility for us to interpret truthfully. The appearance of a cell phone and what we interact with can tell us nothing about how it works. Yet what we know about this interface is perfectly useful and sufficient for most people to act upon. Yet it is still true the facts of its imperceptible components.

We interact with the phone, the subjective truth of it is only in what we interact with, but if it fails to work, the unseen reality presents itself as if through magic. It is with those deeper elements that we now must interact with. It is the deeper, objective elements that only serve the surface level elements. Just as in some way, the objective facts in our lives have to accommodate for the truth of our surface experience.

It is only in understanding our experience that we can truly develop.

“To know the exact shape and dimensions of the Earth is undeniably progress. But whether it’s round or flat doesn’t make a great deal of difference to the meaning of existence. Whatever progress is made in medicine, we can only temporarily treat sufferings that never stop coming back, and culminate in death. We can end a conflict, or a war, but there will always be more, unless people’s minds change…”

Revel & Ricard in The Monk and the Philosopher

The Naïve and Ecstatic Truth

Yes, I appear to be advocating a naïve truth that relies on senses even when they can be deceptive. But there is the truth of having the beginners mind. We sometimes get further from a truth by rationalizing it and creating ideals about what causes our experience. Ideas steal from experience. We see suffering and we think, with reason, of something that person must have done to earn it. Doing this keeps ourselves from the sympathy that might create meaningful action. Human experiences can be made into robotic computations without the element of subjectivity. Instead, we experience the situation as it is, and understand how we are interpreting it through other experiences.

Yet this is still a naïve truth; there is no sense in denying that. The truth that we find through our subjective experience is not objective. It is a truth that comes right out of a deception. Our experience is by its nature deceptive with its limitations and motivations. But since we are the only carriers of truth, we cannot claim the only truths must be objective, perfectly representing reality, existing without the perceiver. It is in being deceived that we experience a meaningful truth.

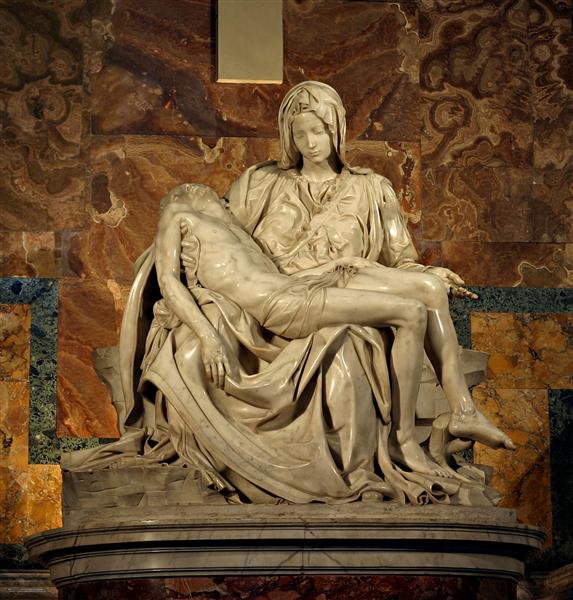

What a meaningful truth looks like when it is created by a human? It is an art. Art is deceptive, but in its deception, we learn about our experience. A story for instance is a lie, but it presents a truth that could not be said using ideas and logic. An “ecstatic truth” as Werner Herzog has called it.

“Does Michelangelo deceive us with his Pieta, one of the most beautiful sculptures on God’s wide earth?”

Werner Herzog

“Exaggerate things in such a way as to capture their shape and substance, capture what life felt like…”

Anne Lamott in Bird by Bird

The ecstatic truth is one that lends itself to the freedom of the student and the wisdom of the teacher. When we create only the objective truths, we neglect that the freedoms of people to learn their own truths, to understand for themselves. We expect people to have faith, and call us the authority, when we have merely passed down facts. But we do not suggest to them that they can find out for themselves how to discover truth. For this reason too, we need a definition of truth that contains humanity within it, that is concerned with being understood and merely not accounted for.

“What distinguishes subjectivity from objectivity is not a denial by the former of “the facts” of the latter; rather, subjectivity adds to Reality a personal perspective and values. I shall call the result of this addition surreality (literally from the French), “reality plus.” The passions the bearers of values, constitute our world, our surreality. Reality is not the world of concern in this book. My concern is with the world we live in, not the lifeless complex of facts and hypotheses that one finds so elegantly described, without a trace of passion, in the pages of our best science textbooks.”

– Robert Solomon in The Passions