Our intuition about truth is based partly on our familiarity with our experiences. On the level at which we experience the world is typically what we are most inclined to trust. Our basic belief lies not what we say or hear about the world, but what patterns we have seen for ourselves. We rarely have reason to doubt the main content of our senses. However, we should realize that there is more beyond our surface level experience. We can interpret our experiences according to the unseen workings of our mind and the world.

For us to recognize and theorize about the patterns which exist behind our senses, we have to use tools for bringing them to the senses. Through these tools we find another indirect path towards perceiving the world. But to use these empirical instruments we must understand how they, too, have deceptions and limitations. There is never any simple revealing of reality to our eyes. But I will discuss the limitations of these tools in another article. For now, lets discuss what types of tools there are and how we use and create them.

Deception and Limitations of the Senses

As we know, our senses can be deceptive, they can be limited, or we simply do not have an innate framework for understanding some phenomena. In the effort to see an accurate world, our senses are interpreted with innate tricks that bring the complex information into something comprehensible and accurate. When the tricks of the visual system are exploited by a human invention, we call them optical illusions. So it must be assumed that our senses can get us to viable truth because of their very formation in the true world and their reliance on an interpretation of that world for our survival. Besides, we have no other means to a conscious truth, but through the senses one way or another.

When we inquire into how the world works, into physics, biology, psychology, sociology, and all other domains of study, we are trying to represent underlying mechanisms into the form our senses can detect unambiguously. For this reason, we have to use tools that allow our senses to get beyond their natural limitations to help us inquire about these things.

This is one of the essential characteristics of science. Scientists use instruments to measure and show us what we could not comprehend on our own (i.e., controlled experiments). Science is a method which mistrusts the intuitions, searching for the methods to remove the ambiguity and bias from our observations. In designing a scientific experiment, one sets up a situation in which we can observe something with clarity that we could not before.

What are some of the tools of inquiry? And how to they expand what is perceivable to us?

Types of Tools

Tools of inquiry are anything that will extend one’s senses deeper, make perceptible systems which are not, or make more discreet something that is normally only a vague perception or intuition. Sigmund Freud writes some about this in his Civilization and Its Discontents.

“With every tool man is perfecting his own organs, whether motor or sensory, or is removing the limits to their own functioning.”

Sigmund Freud

The following list may not be fully comprehensive, but it is adequate for describing the types of tools we commonly use.

Extending and Transforming the Senses: Instruments and Tests

“By means of spectacles he corrects defects in the lens of his own eye; by means of the telescope he sees into the far distance; and by means of the microscope he overcomes the limits of visibility set by the structure of his retina”

Sigmund Freud

The best place to start is with the tools that amplify something from invisible to visible. Microscopes and telescopes do this simply with lenses. We can also convert imperceptible information into perceptible such as infrared cameras that allow us to see light beyond our usual spectrum.

The litmus test is how we perceive acidity or alkalinity. It is a paper which changes color to red or blue based on the pH of the liquid it encounters. We could probably refine our taste perception to recognize pH fairly well, but it is much easier (and safer) to perceive the changing color of a test paper. This test also reduces some of the ambiguity by giving us a result that it more easily differentiated from other similar results.

What characterizes this tool is its converting of something that cannot be normally sensed into something which can. To do this well, we must understand a good deal about what is involved. Although what they do is simple, how to create these tools is much more complicated and often requires wide-ranging knowledge—such as in lenses and light.

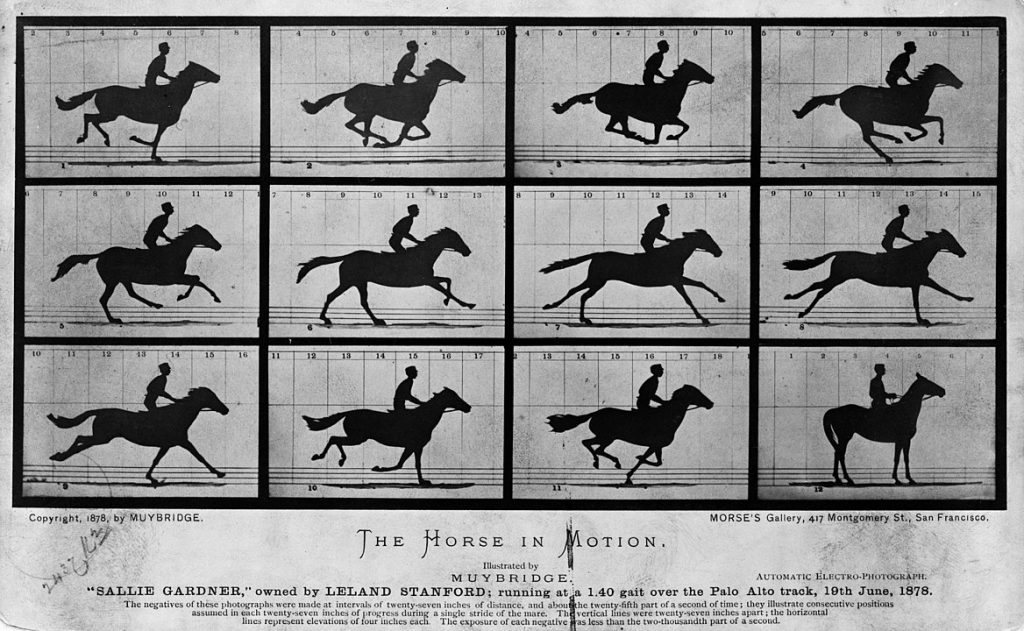

External Memory: Diagrams, Charts, and Records

This next tool would be basically the same if we were to consider memory a sense. For things that are witnessed across time and space, we cannot comprehend exactly. If we already know perceptions have the potential of bias, distant memory is sure to be subject to inaccuracy. We are biased by what has recently happened, by our current perspective, and by what evidence is left of the event of the memory.

To expand this capacity of memory we invent tools to record experiences, compile them, and create an idea of the wider scope which we can now see. With better “memory” we can be better predictive of events and patterns even when our intuitions seem to point elsewhere.

“In the photographic camera he has created an instrument which retains the fleeting visual impressions, just as a gramophone disc retains the equally fleeting auditory ones; both are at bottom materializations of the power he possesses of recollection, his memory.”

Sigmund Freud

Like photographs, we have several other tools that allow us to use collect and reexperience moments. The photographs record a version of the physical world independent of our initial experience. In general terms, what these tools do is create evidence of an event to be seen later.

This type of tool can be combined with the first and we can get a tool that both converts a measure into something visible and leaves objective evidence behind it. The rain gauge is a simple example of this combination. We cannot simply know how much rain has fallen through the senses nor is our short-term memory accurate enough to keep a good record of the total rainfall anyways. The rain gauge converts the ambiguous amount of rain into a more visual form and holds that record as evidence on into the future.

Writing and taking notes also falls in line with this extension of memory. It leaves evidence of some thoughts we have.

What we aim to do with what we record is usually to establish a pattern in which we can understand a long-term process. An example is the concept of “climate.” Climate is an abstraction, we cannot see climate, but only witness it through time and through travel. We all have our vague idea of how the weather has been trending but we tend to be biased by more recent memories. To bring climate to a visual level, we must have recorded what information is relevant and put it into a single visual. Maps and graphs over time are what gives us a conscious idea of what climate it beyond our intuitions from our memory which can be horribly inaccurate and limited to only where you have been.

Exactness of Measure and Statistics

What goes along with records is our creation of mathematics and statistics. Where our intuitions perceive the overall gist of a situation, mathematics is a system of exactness or, on the other hand, accurate averages. Like in the first tools, we can convert what is perceivable into something numerical, and we can preserve that data as evidence of an occurrence. Number systems allow us to notice the difference between two musical notes that is practically inaudible. The measure of sound can be converted into numbers and even the most subtle differences can be comprehended, albeit abstractly, by us.

Mathematics and statistics also allow us to use that information to draw wider and more accurate conclusions. We can measure probabilities and patterns where our intuitions may tell us another story. When we see the statistics of plane crashes versus car crashes, we may sway our anxieties some in a more rational manner. Since mathematics is a “universal language” we can see relationships between many things, leaving very little up to our intuitions of probability. The only limitation is the cleverness it takes to build these tools and measure what is seemingly immeasurable.

Language and Concept Definition

We have already mentioned writing as a way of keeping records to extend “memory.” But much of what we write or speak about is abstract and open to changing meanings based on how we use language as an action. We have attempted to make language more like mathematics where it has stricter definitions and is more based on relationships between words than the social use of those words. For instance, we cannot conceive of a “round square” because our strict definitions of “round” and “square“ prohibit it. What we probably think of is a square shape with rounded corners. But that is not a round square strictly speaking.

Our network of defined concepts is actually a tool for extending our sense of conception. When we put strict boundaries around a concept, we allow ourselves to treat it as if it has a structure which brings it into existence that can be comprehended. Again, if we define “climate” very strictly, we can cram into a word, a lot of meaning to later expand upon that meaning to further the understanding of other concepts. For instance, while I earlier defined “tools of inquiry,” I can now expand out the implications of that definition. Thus, making a vague subject become somewhat stricter so that we can understand a pattern of how we seek truths.

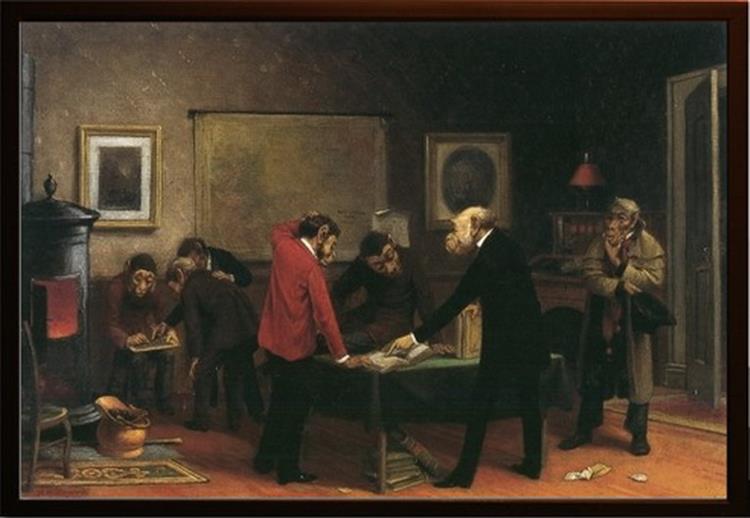

Art and Free Expression

We now come to a definition of art—one of many. Of course, art evades strict definition, but I merely want to propose that part of art is always a tool for inquiry. We see art as very much unlike the other tools of inquiry, but this is because the truth that it seeks is one which is much more evasive. For the sake of simplicity, I will talk about visual art, but all forms should apply to this equally.

The vastness of human life and consciousness is fleeting and subtle. Art, as a tool of inquiry, attempts to symbolize the subtle aspects of ourselves and our consciousness. By attempting to unlock such an ambitious reality, art combines many if not all the other tools. How else could we make the human psyche any more comprehensible?

Art, like a microscope, transforms an imperceptible emotion into a visual medium for us to perceive its objective result. Art, like a rain gauge, will allow fleeting moments to leave their evidence like in a spontaneous brush stroke, even if it is painted over. Art, like mathematics, abides by rules of proportion and values which an artist must obsess about to convey an intended meaning. Art, like language, works within the bounds of strict definition (of style perhaps) on which one builds further understanding.

I think, not only is art important as a personal form of expression, but when you fit it into this list of tools for inquiry you realize that we have emphasized something about art that we do not emphasize about the others. Art takes a skill and practice in both its creation and its interpretation. We think the other tools naturally reveal the world to us, but we need to understand our relationship with these tools.

Creating These Tools

We sometimes forget that it is up to us to create these tools and to not take them for granted. What is true innovation in the world of understanding our world is when we create a tool of inquiry that helps us to perceive something in reality which we have not been able to do so before. Whether it is a scientific instrument, a new form of art, a more refined definition for a concept, of a mathematical algorithm, these are all creative endeavors that seek to reveal something which we had only been able to guess at.

For us to create better tools of inquiry, we must understand the relationships between things in the real world and how we might create situations in which those relationships can be perceived. Curiosity is at the heart of this endeavor. When we try things and observe the consequences, as a creative person does, we begin to understand how to perceive the subtlety of the causal relationships involved.

Any of these tools can be created like a fiction writer might write a story by placing characters in a situation and exploring how it might naturally unfold. We set up experiments the same way. Consider, how helpful this is to a child learning social skills. They try a mean thing, and with any good observation of the result, they can see the interaction between their action and the person they did it to.

This sort of curiosity makes us become scientists of our own experiences. If we try out creating situations, and observing the results, we begin to see the patterns in our lives which have once been imperceptible. We do not need to create something for the world, but we can use these tools in our own lives and in how we act in it.