As with many of the concepts in psychology and philosophy of mind, the term “thought” is extremely vague. This vagueness has to be one of the main hurdles for much of our discourse on psychology and understanding our subjective human experience. Yet I do not think we would benefit from creating a totally comprehensive definition of thought, nor can I (or any of us) pretend to be able to put such a flexible concept into a neat, confined box. Here I am going to talk about one aspect of a thought which I think can lead us into understanding what a “thought” is.

One reason we have struggled to define thought is that there are apparently thoughts which we have that are never known to us nor have a major effect on our behavior or experience. We need to briefly discuss what unconscious “thoughts” are so that we can have an idea of what makes up the conscious ones are. In the end, we do not have a hard and fast description of thoughts, but we can begin to understand how our unconscious mind interacts with what we experience as going on inside our heads.

Thought as the Sum of Subtly

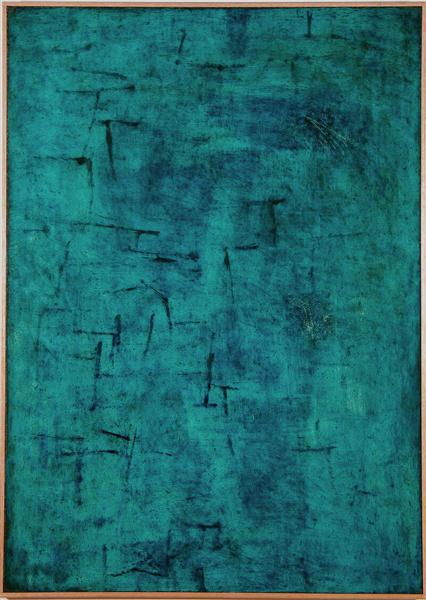

I believe that part of the reason we struggle to define thought is because much of it is formed without us experiencing it consciously or being able to define it in words. Also, many of our thoughts do not appear to amount to any physical changes to the world, or even mental changes to the body or neurons or experience. So how do we label something which doesn’t present itself or have any observable outcomes?

If mental phenomena cannot be objectively observed, do they still merit the title of a thought? Or can we even grant that it ever existed? My answer is “not yet.” The way most of us talk about thoughts is in terms of the conscious portion of them. So, if we use that as our starting point, we can say that all that is not objectively observed as a thought plays only a role in the foundation of a thought.

As an aside, I believe we should form our philosophy of thought around a pragmatic, consequential definition of thought. This comes from the idea that we are not only thinking beings, but also underneath that we are practical, motivated, and embodied. With that being said, I do not think of inconsequential thinking as being unnecessary but that thought always serves some practical purpose, and is consequential beyond our ability to predict.

William James makes the writes the example of how readily we make the assumption that actions and thoughts are inconsequential, when in reality their effects are subtle. Many people will say, “I won’t count it this time.” James responds with “Well! He may not count it, and a kind of Heaven may not count it; but it is being counted none the less. Down among his nerve fibres the molecules are counting it, registering and storing it up to be used against him when the next temptation comes.” I hope to elaborate on this in the future.

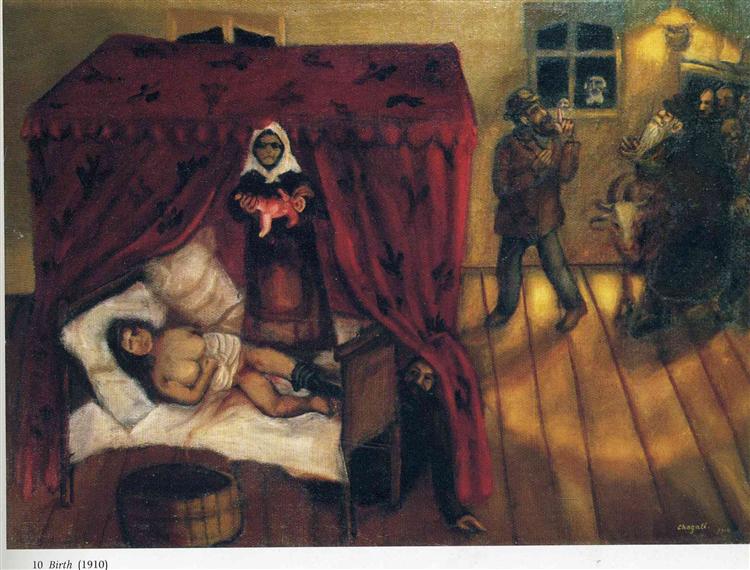

The formation of the stream of consciousness is a joint accumulation of many neural activities which are all active as forms of short-term memory—or residual activity from experience. These patterns of activity, or proto-thoughts, play a small part in creating the whole of a conscious thought, giving it context and allowing us to fully interpret it. They are essential for defining the meaning in the experience we currently have, even if they are not conscious themselves. We cannot reduce a thought to simply the verbal or objective content when so much of it arises from predictions and subtleties in unconscious experience.

When we reflect on past thoughts, we are grabbing the objective parts and leaving out the context in which we originally thought them, and we bring in a current context. We take with us the words, faint perceptions, and other related memories, and add our current knowledge and emotional context. We have a whole new thought as we think that we are accurately recalling a past experience. This is why many thinkers have said, in several different ways, that we cannot think the same thought twice.

Hume’s Idea

Building on a previous article, we have so far described the origins of a thought. I want to now look further into the nature of these origins. Let us call the units of the unconscious origins of thought “ideas.”

Before the conscious thought, the proto-thought is not a solid definable thing, but an activated neural center connecting things and experiences. If you can imagine a neuron in the brain which extends itself to several ideas and if active, all those ideas gain higher potential for activation. But instead of one neuron, the beginning of a thought contains many groups of neurons, and likely millions of groups. But the idea remains the same. An idea is an associative intersection which activates parts of the brain that would be active in the case of experiencing something. Seeing an apple may make other thoughts far more likely. But it is the subtle tendencies experiences give us that allow conscious thoughts to occur.

Two thinkers have posited a similar notion. David Hume describes “ideas” in their relationship to perceptual impressions (conscious experiences).

“Under [impressions] I comprehend all our sensations, passions and emotions, as they make their first appearance in the soul. By ideas I mean the faint images of these in thinking and reasoning; such as, for instance, are all the perceptions excited by the present discourse, excepting only, those which arise from the sight and touch, and excepting the immediate pleasure or uneasiness it may occasion.”

David Hume in A Treatise of Human Nature

For Hume, ideas are actually faint versions of the original experience. The idea exists in the activation of associative networks, without the thing appearing in our senses. Instead of containing the particularities of the original experience with all the sensory detail, the Idea only has the general experience of that based on prior learning experiences. Little did Hume know, that this philosophy would be supported with scientific experiments showing just how incredibly associative the mind really is—that two experiences can be linked in the realm of the faint, indefinable things which Hume called Ideas.

James’s Partial Actions and Intentions

With a strongly imagined idea, such as when we close our eyes and imagine something, we can display some of the behaviors or even get sensations (the impressions) of the ideas we imagine. William James cites his contemporary N. Lange saying how when imagining an object such as a pencil, someone with eyes closed will make eye movements along the straight line of the imagined pencil, and feel very faintly the touch of a pencil in their hand.

It seems to be that if this connection between idea and impression is so strong, we can have wild imaginations or even hallucinations which distort the boundaries between projected perception and the incoming sensations. There are Ideas present when we have impressions, they are what stick around once the impression is gone, and they are what help define the impression when it is there—or even before.

In a similar way, when we think of an object, its name is positioned on the tip of our tongues as if we were going to say it. Or we think out its sound because it is a more salient which helps bring the ideas more fully to consciousness, as impressions. The idea is something that is not quite objective to be observed, but it increases the chance of that objectivity to present itself, in action, in words, or in creating or assisting in creating a perception.

We typically consider a thought only the result of these associative nodes summating into an objective thing, which can be observed and/or spoken of. That is how we define thought; however, we need to remember how much of it is derived from the associative proto-thoughts. Thoughts are made from inhibited actions and blind sensations. They contain only the associative elements, and they strive to make themselves sensible, more fully in consciousness.

How to Have More Nuanced Thoughts

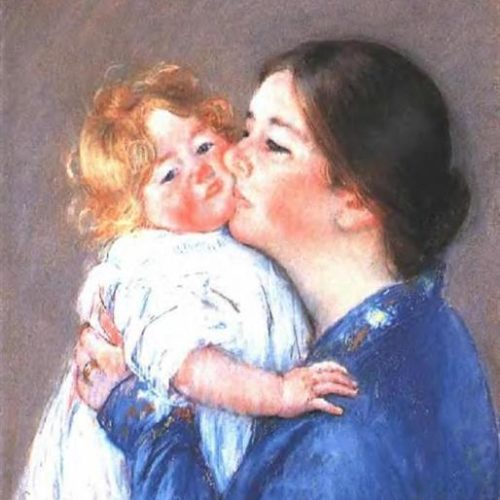

What makes up a thought are the partial perceptions and partial actions which can only become conscious if they present themselves in a form which can easily be sensed or acted out. A conscious thought is typically in the form of language which can both be acted out and perceived. But thoughts, when conscious can play them out in imaginary scenes with subtle tendency to act. Haven’t you noticed the tensing of the body when thinking of something that gives you anger? It is as long as you don’t pay attention to these partial actions and perceptions that they remain unconscious.

This means that a part of thought has only the potential of consciousness, but can influence life without becoming directly observable. We can reinforce and be influenced by the tugs of instinct and habits and peripheral perception, while we do pay enough attention to know what these things are. They are partial actions and projected perceptions.

So if thoughts are the accumulation of partial actions and perception that come to the consciousness in the form of something potentially perceptible or in an inhibited symbolizing action, then the essence of thoughts are more than the conscious content. Perhaps even, the conscious content can mislead us into thinking that is all of our thought. After all, language and symbolic actions are influenced by other people and limited where culture has poorly defined parts of experience, and censored when these things are treated morally, which they almost always are.

What happens when a thought becomes conscious? It does so, so it can connect itself with the unconscious and learn or make a decision about it. It may go one further to influence future thoughts as a background entity. This may go to show that thinking about something or ruminating, unless done very deliberately, may not even improve your planning. It may only re-establish the connections between the concept you think, and the context and definition you already have for it. This polarizes our thought. We reinforce what we think into the patterns we already have. Further reflection is necessary than simply thinking.

The lesson is to find something new in the combination of ideas that come together to make up your thoughts. What is that quiet voice telling you? What aspects of your thoughts have you been ignoring this whole time? That new piece may help shift thought patterns, bringing to consciousness new ideas. This is the essence of expanding the intellect and growing psychologically.