We all have a hard time not procrastinating when doing errands, but the problem gets even worse on creative projects. In fact, the difference between these two things which we find difficult, is so vast that it is common to use small errands as distractions for creative, more meaningful work.

“One snatches at any and every passing pretext, no matter how trivial or external, to escape from the odiousness of the matter at hand. I know a person, for example, who will poke the fire, set chairs straight, pick dust-specks from the floor, arrange his table, snatch up the newspaper, take down any book which catches his eye, trim his nails, waste the morning anyhow, in short, and all without premeditation,–simply because the only thing he ought to attend to is the preparation of a noonday lesson in formal logic which he detests. Anything but that!”

William James

The reason for this depends on how we understand the effort of creative thinking.

Both errands and creative thinking are not usually an end in themselves but a means to a later reward. Our tendency to procrastinate more on creative enterprises can be understood as a problem of motivation, but if we look closer, it tells us something about the way human beings think. The answer to this everyday procrastination problem can be analyzed as a new question, more fundamental to thinking itself. What does it mean to effortfully think?

I find this topic to be full of possibilities in not only becoming a well-rounded thinker or student, but also expanding creativity, improving self-understanding, relationships, and culture. Thinking is a tool which we must use to improve our world, and the first step is to make it clear how to use this tool.

First, we need to redefine thinking to understand what effortful thinking is.

Thinking Is About the Future

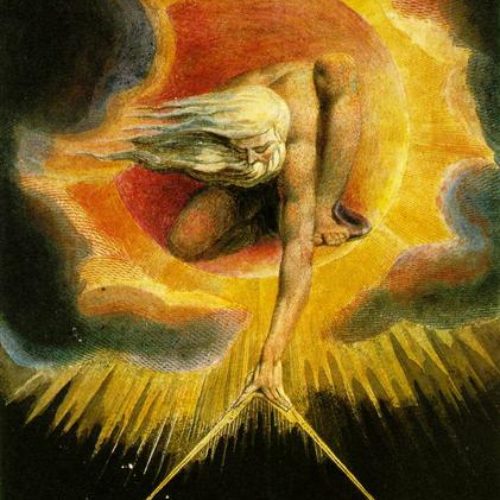

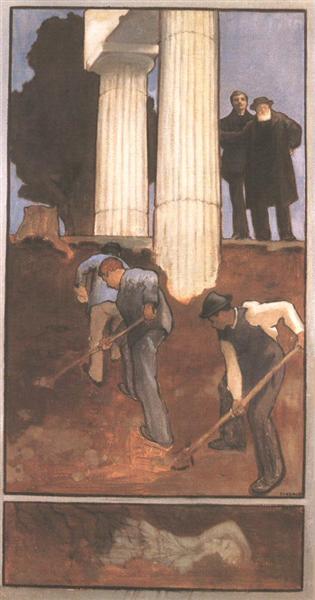

The use of effort is in putting off present desires or emotion to serve a future goal—for a greater reward. Forcing oneself to subordinate immediate pleasures or comfort for a greater reward costs energy with the hope that it will be worth it, accounting for some risk. It is to plant your garlic stock for next year instead of eating it. The crop could fail, but the reward would be enormous if it succeeds.

A popular example in psychology is the “marshmallow test,” where child is given a marshmallow and promised another one only if they resist eating the first one for the next ten minutes. The children clearly struggle to hold off their appetite, debating immediate pleasure and future reward, and perhaps the amount they trust promise of the second marshmallow. Simply watching the recordings of this experiment gives us the sense of effort of resisting natural or habitual tendencies. Perhaps that is the essence of effort.

Thinking is always oriented towards a future reward. As we think, we put off rest and present pleasures to plan or redefine the situation so that we can be prepared later. Most of our rational thinking has very distant points that it wishes to influence and make better, but nonetheless there is some motivating force that forces the mind away from the present and sees the world through a means to a greater end than any present or more proximal rewards.

This is the case for basically all thinking. But not all thinking, or preparing for the future for that matter, is indeed effortful. Habits of thinking make it feel less like an effortful task and more like a natural, comfortable way of thinking. Also, when there is nothing important going on, when we have moments of unfilled boredom, there is no incentive to be present, so we might as well think about the future. Thus ensues ruminations and anxieties. This is not because it is better to prepare by ruminating, but our stressed bodies and society encourages the mental preparations for the worst. Ruminations are made easy because there is not threat or pleasure to pull the mind to the present situation, but there is always something in the future that can be worried about. In this case, we are on the level of thinking, even a level which may exhaust us, but we are still not talking about voluntary, effortful thinking.

We know what effort feels like when we are acting in accordance of a future goal. It is when someone angers you and you must act professionally. It is when the main competition is a year away yet you still practice every day. It is still keeping up with healthy habits before disease strikes.

The difference between eating the dessert and eating something more nutritious can be applied to the difference between thinking impulsively and thinking creatively. The consequences of thinking are basically always in the future, in adjusting our plans and perceptions—or in the case of habits of thought, reinforcing them. We adjust our attitudes towards things based on an imagined possible situation in the future. Ruminating on anger gets one not to immediately act but to prepare oneself to act when confronted by the angering person or simply to avoid that person.

The thinking that requires attention, which does not naturally come, is what is more difficult. But it is complicated by the fact that everything we do or think is motivated by something, whether present or imagined in the future. This would assume that everything we do should come fairly naturally. Why should things require enormous amounts of effort to do what is better for us when we ought to be biologically incentivized to do that anyways? No behavior and thoughts should really surprise us and be without some motivation of habits and desires and the stimuli around us. Why does there have to be uncomfortable effort to do things which we should already be motivated to do?

What makes effortful thinking different can be answered when we treat thinking as a metaphor for problem solving.

Effortful Thinking Starts as Problem Solving

When William James discusses recalling memories, we see an obvious similarity in the way we force ourselves to think and what it means to come up with solutions to problems. There is not a lot of difference between trying to recall a memory and effortfully thinking. When we try to remember some small fact or word, we encircle the idea with our attention on all the concepts related to it. If we are thinking of a name of a species of fish, we force our memory to when we caught it, when we were first told the name, the person that said it, the way the fish looks.

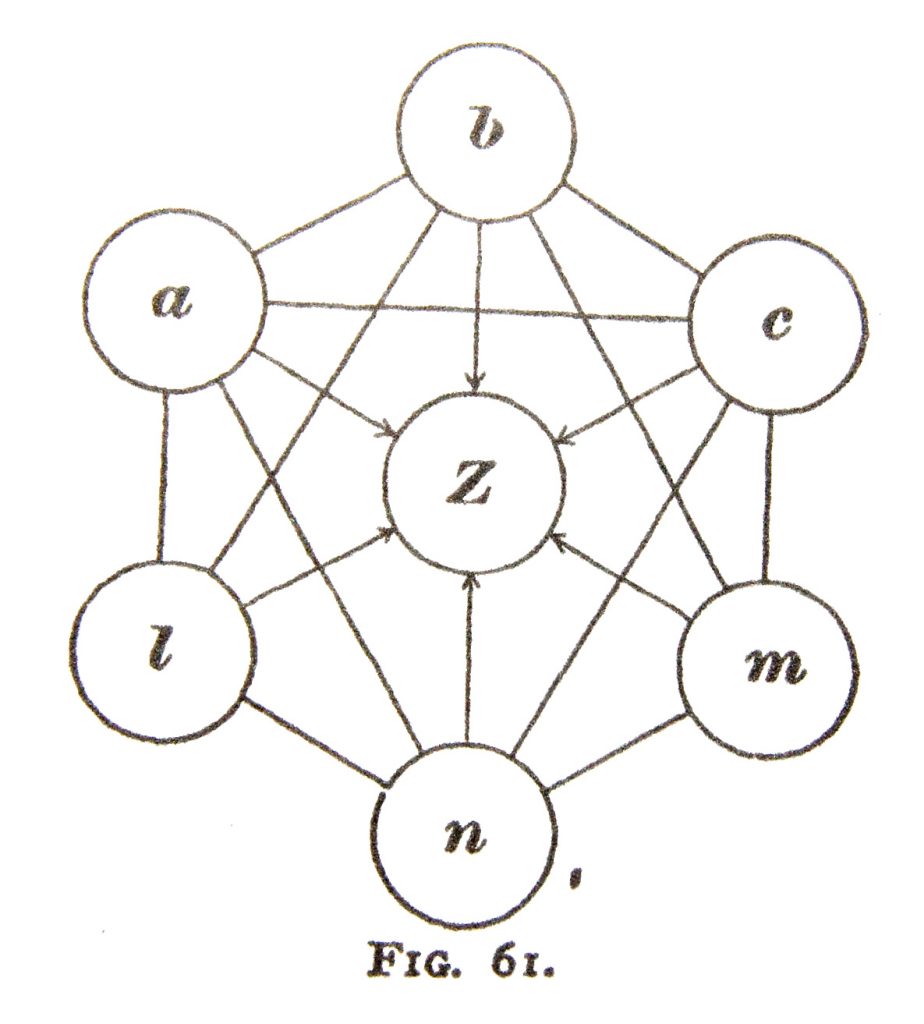

Below is a diagram where the forgotten thing is Z and all the other letters are the things one thinks about while trying to recall Z.

Similarly, solving a problem is coming up with a solution by encircling it with related concepts of the current reality and the ideal solution.

For William James in his chapter on association in his Psychology: A Briefer Course, solving a problem is finding the means to a particular end in the same way we might search for the forgotten word that leaves an “aching void” where we need to find the solution. James suggests that “in striving to recall a thought, for example, we may of set purpose run through the successive classes of circumstance with which it may possibly be connected.” Thoughtfully solving a problem requires the attention and effort to consider many of the factor which contribute to the problem and possible solution. This requires effort, finding specifically what you are looking to recall, by force of attention.

“From the guessing of newspaper enigmas to the plotting of the policy of an empire there is no other process than this.”

William James

But the biggest difference between recalling something and solving a problem is that usually recollection is confirmed easily with intuition. We know exactly if we recalled the right name for something, but in the case of critically thinking about a problem, we can continue thinking to get more understanding of the situations. Problems are usually not solved with one single “Eureka!” moment. Big problems usually take of these moments.

But this still, this recollection-like reasoning goes on all the time without effort. Dissonance and problems motivate quick, effortless thinking. Instead of finding more nuance in our perspectives we use the same habits of thought to explain and solve problems. There is still no straining towards more accurate ideas or perceptions of the world.

The Effort of Delaying Conclusions

The situation often goes like this: we detect a problem, a conflict in desires, ideas, and logic, which draws attention, and then we quickly determine a solution to resolve the conflict. We either use a preexisting idea that can explain the original conflict, or we create a new one that supports the experience.

Daniel Kahneman, the author or Thinking, Fast and Slow, knew that this doesn’t mean that we become suddenly more accurate in our ideas about the world. We tend to jump right to a biased conclusion. The effort is minimized so we can go about our day without any great mental confusion. We do not see any great reward in a more accurate conclusion, so no extra effort should be used. There seems to be no motivation to be absolutely accurate, but only to fill the “aching void” between expectation and reality. Kahneman found that we have already decided our solution before we even begin to reason.

We usually stop whenever we find a good enough conclusion that resembles a solution, even if it’s the first one, just to resolve our cognitive dissonance and move on. We are not terribly motivated to get a perfect picture of the world in our head, but just accurate enough to serve our purposes. But this is not totally bad. Sure, it is lazy, but it is lazy for a reason. There is so much mystery in the world—we simply do not have time to explain everything.

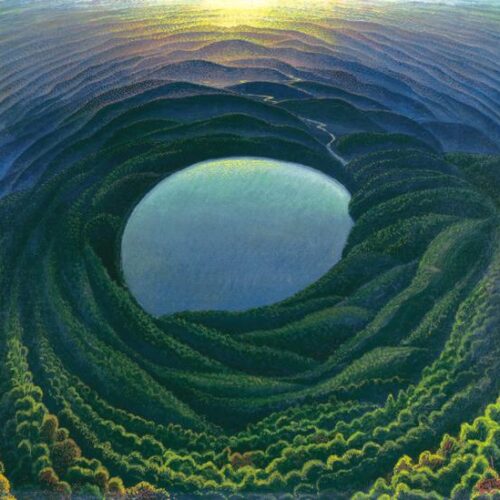

It will never be a singular reason which satisfied all gaps that we put attention towards solving. The truth is found by continuing to question and find many more angles from which to see the problem. The effort we have is to keep our attention on something even after we think we have concluded the problem. We have to keep turning the clay over and over until we see the problem on all angles and then begin to have some conclusions. We get nuanced understanding, not simply a solution that allows us to move on with our lives.

This takes great effort because it inhibits the tendency to go straight to the conclusion. So in a way this is putting off a present tendency of thought for a more long-term one. So it still comes down to the time in which reward will come, but it is relative to which reward comes sooner, or which effort seems more worth it.

Conscious thought is manifested as conclusions. Effortful thinking is to suspend these conclusions a little longer, to have more information to contribute to them. The effort is whether to hurry and have your conclusion now, or let attention stay on the problem long enough for a more nuanced solution. Or in the case where you know the answer but you cannot name it, the effort has a known goal, that is why we are so tempted to try recalling the word, because we know the reward of our effort: to speak with concision.

Freedom in Creative Thinking

Recalling something from memory that you nearly forgot is an effort that is not necessarily creative thinking—for there is only one solution. But most of the conclusions we settle on have the option for creative additions. This means that the effort can be spent indefinitely on the problem, until you must commit to it, with action or speech. Like if you are speaking and stop to think of the right word but so as not to lose the attention of the listeners you quickly pick a less fitting word.

Creative thinking is equivalent to putting extra effort into finding more solutions, learning more about the problem, filling that gap that James describes when recalling. It goes beyond merely adequate conclusions. We are creating nuance instead of assumption, finding more ways to see, more angles. A painter may look at something with great effort to see more than someone who sees and immediately concludes. This creative thinking is of a universal sort, both in mathematics and in abstract art. It is thinking itself.

William James believed if we were able to do anything with volition, it would be holding our attention on something longer, leaving potential for a gap in understanding. So much may be determined, but this effortful thinking is pretty close to freedom. James quotes Hermann von Helmholtz on the art of concentration.

“The natural tendency of attention when left to itself is to wander to ever new things; and so soon as the interest of its object is over, so soon as nothing new is to be noticed there, it passes, in spite of our will, to something else. If we wish to keep it upon one and the same object, we must seek constantly to find our something new about the latter, especially if the other powerful impressions are attracting us away.”

Hermann von Helmholtz

So it is not an unmotivated effort, but it is an effort that requires a faith in a greater reward down the road. The determination of this creative thinking has to exist to propel the effort of subordinating a quick solution. Does this mean one must believe is some Truth, which promises some transcendent state? The honest of what motivates our efforts in thinking are just as important as putting the efforts in. But most of the effort may be propelled by a simple form of curiosity that sees the novelty in the banal. Exercising curiosity can help mitigate the idealistic hopes one has which can bias one’s efforts in thinking. We do not need to rely on a distant goal to look deeper, but have a constant dissatisfaction with our confidence in truth. Keeping the beginner’s mind, we do not have to make false promises of reward for our lifelong efforts.