Philosophy is notorious for asking the esoteric questions about apparently the simplest of notions. And for the most part we scoff at them as irrelevant to our actual lives. Who can blame us for that? It isn’t easy to apply these things, and the high-falutin language they use isn’t much of a guide. In this article, I will discuss one of the simplest things you can question about our experience and hopefully help you apply it to your experience. The question: What is a thing? What is it that we are conscious of, that our attention is on, that we usually call by a name? What defines it, and what has created it in our minds, and holds it together? Does it have substance, or does it unravel the second you take a closer look?

The object of our attention is a strangely perplexing topic; it is all that we know, yet we cannot quite describe its boundaries and aspects. At first glance, you might think it is simply the object—an “apple,” for instance—that you are looking at, but there is something else mixed into the whole activity of attention.

What a Thing Is Not

Our first instinct is to call something by its name, and demand that that is the object of attention. Period.

But what if that thing is seen in a different context? That object takes a new identity. The apple which we identify needs to meet a number of requirements to be an apple, some of them have little to do with color and shape, but that is not the total identity of “apple.” It could also be chopped up and in a pie, and our attention to “apple” will take a strange turn to the abstract apple inside the pie crust. Is our attention focused on an apple or on the abstract “apple” in the pie? What makes up the object of apple is much more complex than the typical image of an apple. It requires a background, contextual rules, a surrounding medium for which the apple can be an object to us. There are rules and multiple factors that go into our perceptions to make them an object. How do we define an apple?

But we also do not randomly define things just for the sake of description and rules. Our attention to an object is not static or inert. Attention is a predicting and assuming activity. We can see and label things while knowing that, deep down, we do not see the actual causes, but something is happening that we cannot see, in infinite complexity. We do not see gravity, but we assume its effects. When we pay attention to things, we are assuming its function in the world. Most things remain still, with little significant impact, but flying objects are never seen still, they are seen as doing something meaningful in the world, and potentially dangerous. Rather than seeing the object itself, we see its potential effects and its precursors.

Finally, we do not see things as a god might, we cannot see from the viewpoint of the universe. Our perception is clouded by our animal biologies. There are electromagnetic wavelengths we cannot see; there are sound frequencies we cannot hear; there are chemicals we cannot taste or smell. Our biology is our ability but also what limits us. Our filter of things in the world is influenced by this biology. We do not have the luxury to see things as they are, but only as we were made to see them.

The Relational and the Contextual

To start off, we can see what the object of our attention relies on for it to be made a coherent object: rules and context.

How much does the object of our attention rely on its surroundings to be what it is? Consider the differences we feel when something is surrounded by a TV screen compared to the everyday world. We can watch TV without any concern that the events on screen are those in our world. A murder on screen is not the same as a murder in real life, we (practically) never confuse the two, and they are different objects of attention.

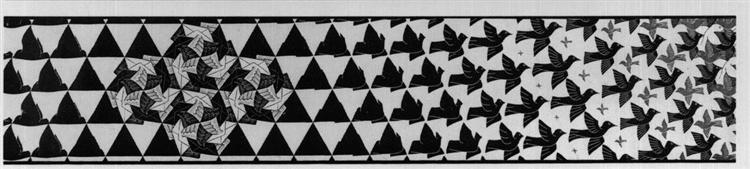

Things as we know them are defined by their relationship to other things, or by the background they exist in. What allows us to focus on “tree” is everything else around it that gives the tree its important identity. But we do not see “tree” alone. William James says we do not simply hear thunder, but we hear thunder breaking the silence. When we hear thunder, somehow we are reminded of the former silence. A constant rumble of thunder has a different meaning, with less shock that a sudden one, and that relationship is psychologically important.

Relationships between perceptions give an object its original meaning. It is like the lamp-or-faces illusion. We cannot distinguish the object because we do not know what is figure and what is ground.

Instances of other figure-ground illusions with the senses are numerous. We get a feeling of cold in a normally mild room after being in the heat. The redness of an apple remains persistent in light or in shadow, even if the color is “physically” different. It is the relationships of objects to each other which give them meaning or apparent existence.

What we might describe as an object is really a series of features and perceptions. This comes from the simple way we know that when things come together in a certain way, if we fit together all the parts, it can be that thing. A square has four right angles, but also the lines connecting those angles must be straight and equal in length. We apply all these rules in order to make a “square” and perceive it that way. This is an inherent logic that operates with this intuition of context and rules.

The Essential and the Real

What holds the things or concepts together like glue is not necessarily the word; the word often comes from a belief that these concepts correspond to a reality, or at least they appear in some way to. Defining a square as four equal lines creating right angles would be pointless unless we can apply this to reality, for instance in geometry’s use in architecture. Creating a perfect square can make the difference between a stable and a dangerous building. We see the world as the evidence of abstract things being applied in complex ways. Somehow the rules and context we give to an object becomes part of how it functions and interacts with things in some objective reality.

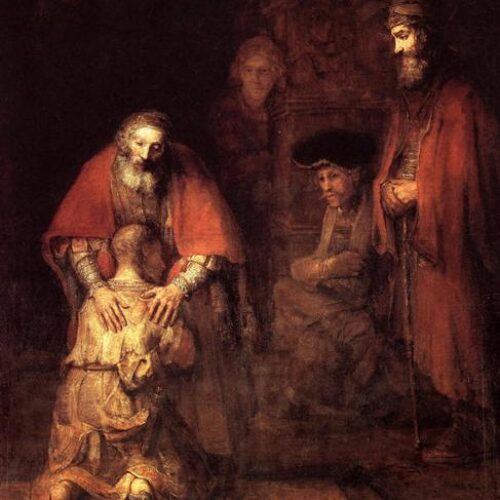

When we perceive, we have an assumption that whatever concepts we see, they will have some function that is thanks to some set of rules. What is “real” is not perceived directly, but is an underlying assumption of how we group the world. Hume’s example of perceiving a billiard ball hit another and cause its motion is important in thinking about the real. We do not perceive the causation directly, but something definitely happened. Our mental theory behind billiard balls tells us that that was going to happen every time. The ball, a symbolically defined thing, had a real effect.

We also know from Hume that we do not perceive the causation. We merely assume it and—as scientists—try to define the terms of what causes it. Newtons laws come very close to being the exact symbols which accurately help us perceive the real, but there is always slightly more. But we cannot witness gravity although we know that somewhere it is true to the world.

What does this do for our attention? Our attention is affected by eliciting a subtle anticipation whenever something which is a known cause arrives in the perceptual field. We begin to anticipate where the rolling ball will go because we assume that there are laws which govern it. Even if we do not know the laws mathematically, we assume them from experience. Our attention therefore reaches into the near future within the present. In another case where we perceive an effect, a howl of a wolf, we assume there was a real cause, the wolf, and in this way our attention imagines the past within the present. This is what gives us a rational expectation of the world, a knowledge of the rules that the universe abides by. It is within our attention, that things will act in mostly predictable ways.

In this way we begin to add in what is important, what has meaningful functions. It is not the howl of the wolf that we need to fear, it is the wolf itself, or better the bite of the wolf, and so on and so on. We learn to focus our attention on things which have effects. But what makes this predictive aspect of attention important in our lives?

The Subjective

What ties these things together is us, literally the complex makeup of the human being who perceives. So far, these things have been described as neutral, like logic and cause-effect relations. But there is almost a filter of motivated perception which we must work through. Something which rises out of our bodies and minds and colors our world.

The prerequisite for seeing an object is to see and seeing is partly an action. The senses give us the images of the world, they limit us in how we see the world. The senses are also intimately connected to motivation. Their biological origin ties us to motivated perceiving.

This makes our personal reality. This makes anything true by adding “For me…” Finishing this sentence will always have a degree of truth. Anything can seem one way or another and in that very moment (if there is such a moment) it is a truth, a totally subjective truth. But once we apply our assumptions of reality and relational knowledge and language, we do not know it for sure. So there is no fully subjective truth, only a truth that walks on all three of these categories.

Meditation

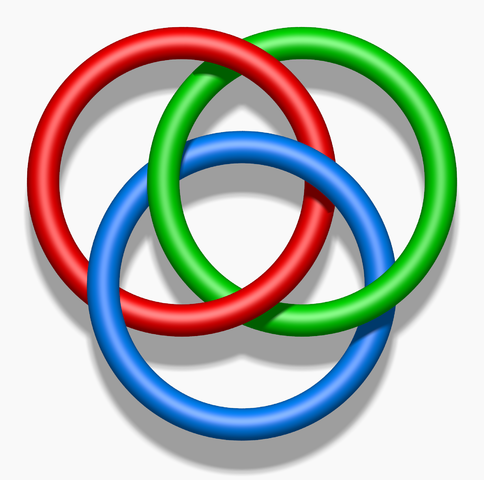

We must think of this triad of parts as tied in a knot. Lacan uses a Borromean know to describe his analogous triad. The Borromean know is a set of three rings where one ring cannot move away from the others without disrupting the others. We cannot be too subjective or else our world is a hallucination and disordered like a dream. We cannot merely work in symbols or else we make a fault of mysticism where our words are meaningless gestures, without touching on some real thing. We cannot visualize the real without noting its relationships, because its interconnectedness is so chaotic and meaningless that action and words are made feeble attempts at description.

Meditation is a holding of attention, of consciousness (I am using the term meditation broadly). When we meditate we focus on one of these aspects and stretch it from the rest so that we may stretch our normally tightly bound realities.

Buddhism describes reality as a vast, “empty,” interconnectedness. Nothing is substantial. The world is empty because the way we define things is based on other things and we cannot directly perceive the Real, but the world is still interconnects somewhere where we cannot see. With the meditation focusing on this part of attention, on the causation and flow of substance of the world, we see the fluidity of life.

When we are mindful of our experience and sit and watch thoughts pass, we are meditating on the imaginary. What we experience has a sacredness which cannot be intruded upon by the other parts of reality. No matter how much we try to make rational sense of it, subjectivity at its purest is nothing and indescribable.

And finally, we can meditate on a word, mantra, or a discrete object. Our focus on a defined object shows us that it is in fact insubstantial. That it is defined by its contrast and not its solidity. The flame which we focus on has no beginning and end.

For us to manipulate the knot is to become more conscious of what we cannot normally perceive. We are kneading the dough of our perception. And from this we can observe many of the perplexing things in life.