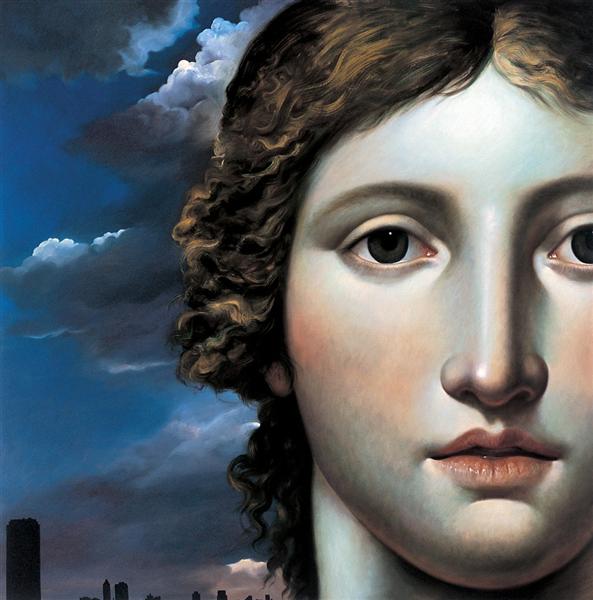

Attention, like action, can follow two different modes. Sometimes our attention is reactive, and sometimes our attention is searching for something. When we automatically react to a stimulus, our attention is turned towards something new which needs to be perceived, because it signaled something important to our well-being. Tracking eye movements and the orientation of awareness to important perceptions has deeply unconscious and automatic origins. A loud noise or sudden change in scene pulls consciousness towards it, but also objects which have been associated with importance can become automatic too. With only this reactive mode, we are limited to attending to what is around us, but that is not the whole of our experience.

Our survival does not depend entirely on our reactions to our local environment. It also depends on things we must seek out. We don’t accidentally happen upon food, protection, mates, or comfort and react to their perception. We are driven to find these things somewhere in the world. And part of the function of attention is to sort out and search for these things in our environment.

Understanding this aspect of attention is not without a reward. We are often people conflicted with the question “what do I want?” In its broad sense, this question may be the question to ask. How does one know what one wants in life? Understanding the ways our attention moves is to uncover slowly the riddle of our personal motivations and desires.

Appetite: Internal Origin and External Action

To lay attention on something that is not in our perceptible field, we must have an idea of what we seek come to us endogenously, from within. When our biological state of homeostasis is disrupted and something is needed to restore the balance, we seek something. The body sends us a message for us to act. However, this message is veiled and complicated by the ways we interpret them. We might expect that any desires can simply come to us by the body telling us exactly what we want and then we seek that thing. But the wanting is derived from a voiceless biological source, one that cannot easily be transferred into an intelligible language.

Instead of directly seeking the solution to whatever disrupted homeostasis, we turn to a general seeking mode. It is obvious that we do not get signals that tell us exactly which nutrients we need to restore balance, but we also cannot expect our body to alert us of other needs too.

Even hunger can be misinterpreted. That feeling of an empty stomach can be a clear biological need for nutrients, but how often do we seek food to relieve stress? Or how often does low blood sugar make us mad at the people around us? These are examples where a clear biological need (or appearance of a need) is misinterpreted.

Rather than getting a purely biological signal, we must rely on our perceptions, what our attention goes to. And for humans, with explicit memories, on the memories that can explain the need to seek. Feeling the pangs of hunger can signal somethings other than nutrient deficiency if one remembers how recently one ate.

Andrea Scarantino and Ronald de Sousa recount a classic study in their article on emotion in the Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy. The study showed how drastically different the same bodily signals can be interpreted give separate situations.

“Subjects in their study were injected with epinephrine, a stimulant of the sympathetic system. Schacter and Singer found that these subjects tended to interpret the arousal they experienced either as anger or as euphoria, depending on the type of situation they found themselves in.”

The general seeking mode can be like a mode of interest and curiosity, or it might be a desperation or an uncomfortable appetite. The internal milieu often determines the general mode, like a way of being in the world, but what we seek is sought through interpretation of the situation. There is nothing about feeling to low energy of calorie-deprivation that necessarily means “hunger,” the same feeling can be “lethargy” or “depression.”

But we learn early on how to interpret subtle feelings. As infants, we would want something without being sure what it was. When we had this general feeling of discomfort, we cried, and our parents tried everything to calm us, and sometimes holding us and feeding us worked, and then we understood what that uncomfortable feeling was, by noticing the circumstances that caused it and those that relieved it.

Projected Attention

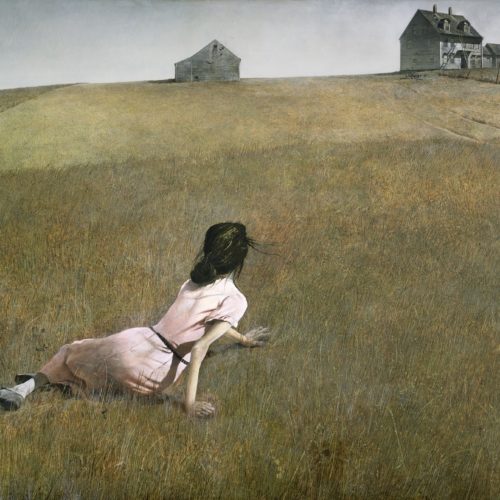

After we experience something that satisfies us, such as feeding, we grow a more complex vision of what that feeling means and how to act upon it. The actions and thoughts that a now more specific feeling leads to needs to grasp onto the world in order to predict and relieve the homeostatic tension. That desired object is created from the past, existing as an idea. Now when we seek something, we project onto the world a lack of that thing, and interpret the world in terms of attaining it.

But that thing is not always known to us. But what is known to us is the way that we project our attention onto our world. In seeking something, whatever it is, we project a logical map into our world and our attention assigns meaning to the things which lead us to our goal. If we are seeking food, then the signs that signify food have important meaning. If we were unaware of what we sought, then the way we attend to signs of food could clue us into what we want.

Not only are the things themselves something we learn do desire when they are not present, it is also the things that signal the thing we seek. If Pavlov’s dog is hungry, it may be highly receptive to hearing the bell that signals food. It may soon anticipate and desire the bell almost as much as the food. Whatever it is we want, even if it is so unclearly defined my only be in whatever signals that idea, and there is nothing legitimate beyond that desire.

With an intense need, from an intense disruption of homeostasis, we have a mind hell-bent on consummating a want. Whatever we interpret our need to be forms the framework of our perception. Our attention is directed to things which most relate to the object of need. “We see what we want to see” is a platitude that comes from the fact that when we want something desperately, we attend to a lack, and we are vulnerable to interpreting irrelevant signs as relevant. Even if what we seek is a total illusion, we can still imagine it only through the clues that might signal it. Consider someone who is seeking an ideal form of love, who’s attention is drawn to signs of the perfect love. This person is left to be frustrated to find that those signs only signified a phantom ideal.

Our seeking attention is a mode of interpretation of the world, seeing only the relevant facts to resolve a tension, and interpreting these facts with values. Our wants seem to be replaced by our interpretation of signs and only partially realize, thus leaving us never totally satisfied and always partly seeking and partly reacting.

Creative Projects and Materializing the Idea

Even if we will never totally satisfy all of our needs, we can still find ways of interpreting our world so that we can more deliberately understand the way we perceive it.

To project our attention is to think about something. And bringing those thoughts to attention allows us to witness the values we give these things. There are ways in which people can practice this to become more aware of their interpretation of the world.

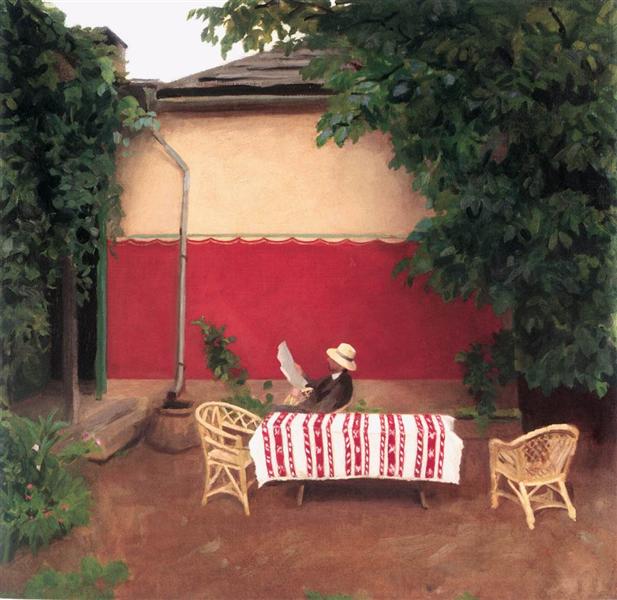

To start, we must be in a mode of projection. If we are reacting to a complex and changing environment such as the one entertainment puts in front of our eyes, we are do not produce many endogenously created thoughts. One must put oneself in the uncomfortable position of creation rather than reaction.

Second, we have to linger on the thoughts that we have. When we are allowed to think and direct our attention around, we tend to seek and quickly jump from thought to thought without holding on to anything. Without a conscious awareness of where our attention goes, we cannot interpret the ways we see our world.

Finally, we must appreciate the fact that our attention has a motive and the things that it focuses on and repeatedly check are things which have value towards a sought goal. This is helped by understanding how projecting our wants onto the world shapes how we see it.

Since our desires are made into these logical maps through our attentive interpretation of the world, we must notice our assumptions when we look past things to seek an idea. We might look past our local community to seek status, and our thoughts regarding people around us will display this unfortunate striving. But it is not only the value we give to those people that alert us of our goals, it is all values.

Describing the world, even in an objective way will lead us to uncovering the things we value. But it is in creative ventures where the desires come to awareness. It is creating or describing something concrete that forces our values that we often overlook. Perhaps most of all in journaling or letter writing. Try writing a letter to someone, try talking about an object in the room, try journaling about the day’s events. Even conversation with someone close can help. These concrete things already, by nature of being remembered and by nature of being noticed and freshly described, will have lesser known values projected upon them.