Although our stream of consciousness, by its very nature, exists only in the present, its directions are determined a great deal by the past. Our stream of consciousness depends upon the connectivity of past ideas with current incoming stimuli. This is a general rule, but it is complicated because, unlike most animals, our stream of consciousness tends to go on and on in our heads while nothing exciting goes on around us.

Our thoughts interest us plenty as we ruminate and imagine. Attention is usually elsewhere when we are on a long drive or while taking a shower. Of course, this ability to think in chains of ideas without external input is a huge advantage that signals a certain level of animal intelligence. However, there is no pure thought; our minds still are not even “spinning frictionless in the void,” as the philosopher John McDowell put it. Even with thought’s self-perpetuating ability, the stream of consciousness is always taking information from other sensory inputs and conflating it with what we may think of as pure thoughts.

Discussed in previous articles, long-term memory and working memory play essential roles in the stream of consciousness. Long-term memory lays down the pathways for concepts to be recalled or quickly used for interpretation. Working memory puts recent things at the front of the mind so that relevant or recent information can guide where the stream of thought takes us and improve our ability to quickly interpret events.

However, there is no discussing how memory works without reference to incoming information. Memory can only be realized in its relationship to the present information that helps it be recalled. What helps create the transient thoughts, which we barely grasp before they vanish with hardly a trace, is the job of memory and perception of contextual things which don’t make it in their full form to conscious awareness. The question we ask follows: How do perceptions come in, interact with memory, and become part of our stream of consciousness?

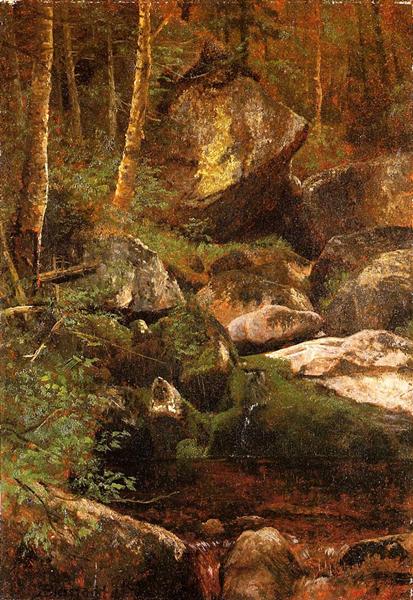

Parallel Processing: the tributaries

We often wrongly assume that we are aware of all the information that affects our thoughts and behavior. This unconscious information is not secret or anything, but it was habituated to, and we no longer need to pay attention to it. We’ve grown accustom to walking in the park to the point where we could easily read a book while walking. The things we encounter on our walk are what we have grown accustom to seeing, things which elicit no surprise or need for conscious deliberation. It is not that these things are not emotional or unimportant; they are rather just things which we know how to deal with without any complex maneuvering that requires attention. For instance, we can listen to the verbal content of a distressed voice, without attending to the distress itself, but react as if we have. While paying full attention to what the person is literally saying, we automatically receive the information of what they are saying emotionally.

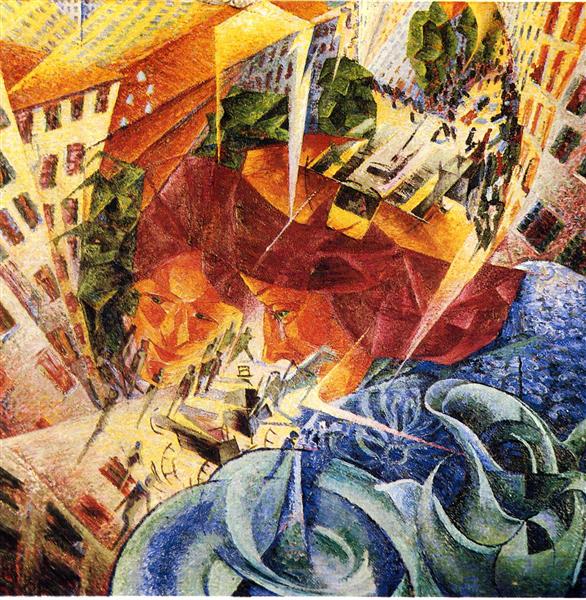

We are able to do many of these automatic reactions at a time. This processes is basically the effort of the working memory, as it stays below the level of awareness, but can be recalled if needed. Because they are automatic and unconscious, several processes can be done at once without confusing the conscious mind. For that reason, this is called parallel processing. We have several going on at once, and although unconscious, parallel processes can bring particular thoughts to consciousness, or color them in a different shade.

For that reason, working memory can appear conscious but is really “pre-conscious,” waiting to be recalled or else it is never brought to consciousness. Like the feeling of a seat you are sitting in. If you get up, you can still consciously recall the feeling you might have had, but that opportunity vanishes quickly if you move on to another task requiring attention.

These things contribute to our feeling of the situation. In another article I compare this to the ground of a figure-ground phenomenon. Like an upset stomach will contribute to the ways that you treat someone, several different perceptions being unconsciously received, can affect how we frame and feel about what is in our stream of consciousness. This person you might be talking with may appear more irritating because of what your stomach is quietly telling you.

Summation of Input

With all this processing of incoming information, there needs to be a more singular conscious result, basically because we can only maneuver our body in a single way and aim our eyes in single directions, our limits of anatomy force us to take in one thing at a time, but we can allow that thing to have deep complexities going on underneath is.

“I believe that the problem confronted during evolution of complex organisms like ourselves was not to unify conscious experience but rather to avoid destroying the unity that Nature provided. . . . singleness of action is a vital requirement; if motor responses were not unified, an animal could quite literally tear itself apart!”

Rodney Cotterill

While we can do many unconscious things at once, we still only have room to summarize most of the information that seems most important.

A relevant idea that originates from the science of perception is the summation of stimuli. For us to perceive many ambiguous things accurately we often rely on several sources of information. A common use of this is combining visual and auditory information to understand the words someone is saying. A common example used to demonstrate this is using a video recording of someone repeating the syllable “ba.” Then the video is changed to someone saying “fa” with exactly the same audio. Your mind is totally convinced that you are hearing a different sound but really it is the influence of visual information that is making the meaningful perception change. This is called the McGurk effect and is yet another example of how perceptual illusions help to get us to a meaningful picture of the world as I’ve written on earlier.

Summation of stimuli also applies to what is recognized as the most meaningful part of present awareness and how to interpret it. We cannot think about a loved one with a singular part of our brain; he or she is defined by so much more underlying information. In the attention of any object, there is information being included by all sorts of other sources, like the current state of your body (stressed, relaxed, etc.), things in recent memory, or memories from long ago that have strong emotional values. All of these things are summed together to create a path for how to interact with something.

These streams of parallel processes create our conscious experience from information including internal milieu like hormone balance, sensory perceptions, and memories of the past. This means that, because parallel processes are both reactions to the external world and inner workings of the body and the thinking mind, there is a constant balance between internal thoughts and thoughts pertaining to the external world. Our stream of consciousness moves between these two and combines them regularly depending on which are more salient and emotional. An abrupt shock can erase the internal chain of thoughts for a moment, but it kicks off a new one. And great mental strife and insecurity can cause someone to ignore the whole world around them.

Serial Processing: The Stream

“Automatic processes involve no conscious control. . . Multiple automatic processes may occur at once, or at least very quickly, and in no particular sequence. Thus they are parallel processes. In contrast, controlled processes are accessible to conscious control and even require it. Such processes are performed serially. . . one step at a time.”

Robert Sternberg in Cognitive Psychology

Since the need to reduce the object of consciousness to basically to one thing, but spreads widely over many connotations, we must be quick to gather adequate amounts of information. We have a constantly shifting attention; perhaps for 3 seconds or perhaps a mere moment do we have a single thought unchanged. This stream of consciousness, being bound practically one thing at a time, is what we call serial processing. As opposed to parallel processing, serial processing is conscious and constantly shifting and changing.

Our relationship to the past is thus much more fragile. Memories come to mind only by general motivations which sum up to the recollection. In fact, any given moment for us is quickly lost to the past, being more and more difficult to recall accurately.

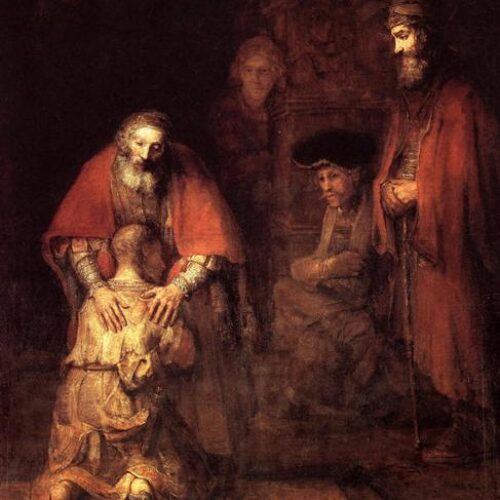

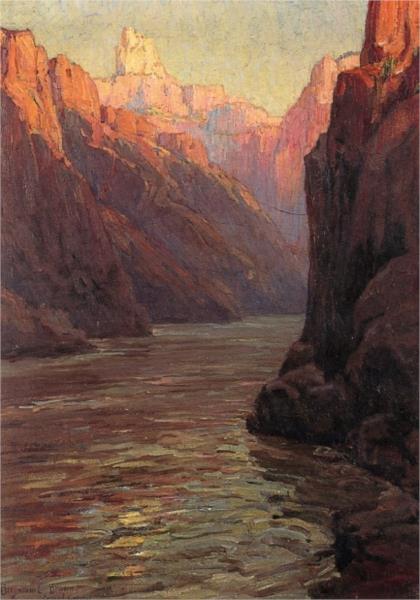

It is no wonder William James has chosen the stream and an apt metaphor for consciousness. At any moment in the stream of consciousness you can measure the water to see what gave rise to the water, what are its sources? At any moment we can stop and reflect. But the water of the tributaries mix together and become nearly impossible to detect the sources of the current water sample. It is the sum of the multitudinous sources that creates our conscious experience, however narrow the stream flows. Most of our parallel processes are automatic and learned through experience, thus they do not make up the main stream of consciousness.

Although the object of attention is conscious, even for only a second, its definition is not necessarily conscious, it is defined by the other workings of the brain that happen while you focus on this thing. We do not realize the source of our feelings towards a sibling or parent, but know better of how they appear, and we may have some reasons for our feelings, but the deeper parallel processes which constantly organize perception, are defining these people without our knowing.

Meditation can be done which looks at each thought and looks for the definitions of each thought, and consciously defining them will break them up and make a new definition. Catching a thought go by, is no easy task, feeling it is even harder. And perhaps hardest of all, is understanding and coming to terms with its source. Getting at the intricate definitions of the things, means to come to terms with the transience of thought, and what it means to have memories.