Especially today, we have a hard time understanding the erratic behavior of our own attention. It is our gateway into the conscious world, and for some reason, we can barely control it. In the end, it seems like this problem has more consequences than being unable to pay attention in class or not being able to enjoy a difficult book. Our lack of deliberate attention seems to be an existential problem. Our whole world comes through what we pay attention to.

But before plunging into the practical tools for controlling attention, we must first adjust our attitude towards it. The way our attention works is supposed to be for us, not against. Before we control our attention, we must inhabit it though its basic function in our consciousness. That function is to teach us though the senses.

Attention is the Impulse to Learn by Looking

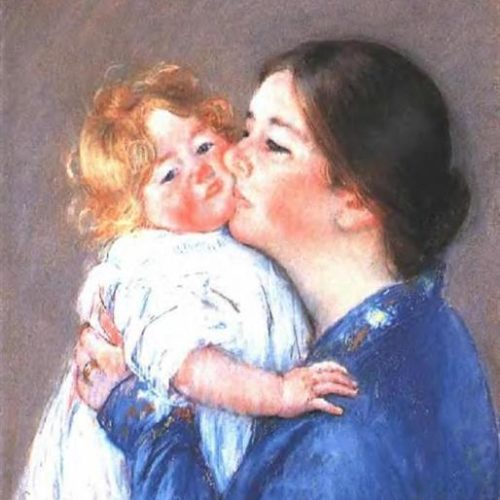

Our childhoods are spent on discovery and curiosity, trying to uncover how the world works, how our body works, and what is stable in the world. A child’s attention darts all around, picking up patterns, interacting, and learning from the consequences; there is so much to be learned.

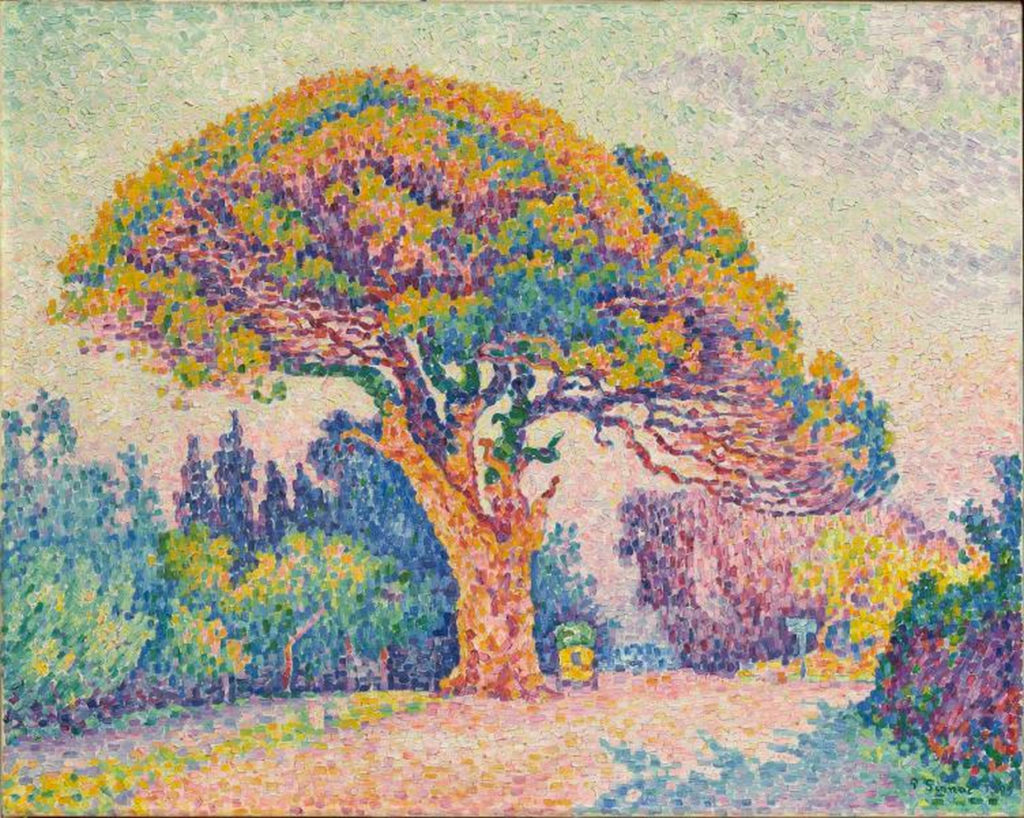

Attention brings consciousness to surprising, unpredictable, or interesting things. These of course are practically synonymous—the category of things our attention goes to is wide and includes many adjectives. But the mechanism is discrete: attention goes to what does or could not fit in a picture of the stable world. And for a new mind this might be almost everything.

This period of life sets the tone for expectations in the future. A secure child will have an adulthood of expecting security; an abandoned child will become an adult expecting abandonment. A less dramatic example is when the ball is dropped, we expect it to bounce. We are shocked by the cases when it doesn’t.

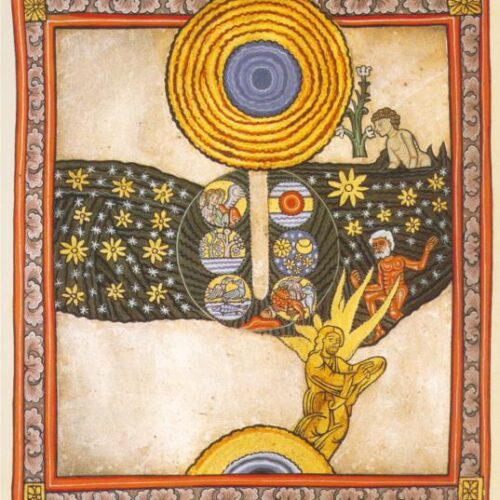

By setting the scope of attention upon something, we are processing the information and creating new knowledge of the nuances in it. And if the details we notice are stable, we add it to the banks of expectation. Without the attention, we cannot add stability to the unpredictable object, after attention its components get some stability. A mysterious cave compels attention. Once inside and attention scans it, intellectualizes it, finds it to be predictable and innocuous, it becomes stable, conceptualized. It is only a cave with all the elements that other caves have, nothing unique. And then we can ignore most of it that is no longer mysterious to us.

We look at these interesting things so that maybe later we will be able to ignore them. This is curiosity at its purest—learning and getting used to that knowledge. Attention has a tendency of going towards what is not conceptualized, what is not stable.

Learned Automaticity and Predictions

Since birth our attention has been on so many things, many of which seem constant. Some things are very constant, like the physics of the observable world. Some, especially regarding people, are not so constant, but we create laws of behavior like laws of physics to help us navigate the social world.

What we have learned as stable in the world, we no longer pay attention to. You no longer need conscious attention of even complex activities, because you have been doing all your life and even obstacles are predictable. Learning to walk used to take attention to the muscles of the body. A physical therapist could tell you all the complex synchronization of muscles required to walk properly, yet we no longer think about them even when facing obstacles. A philosopher pacing in her study, deep in thought, will rarely trip over the clutter of books and furniture.

A way of describing the usage of all this material we’ve learned is by calling it predictions. Lisa Barrett uses this term in her book How Emotions Are Made to help us understand how what we learned in the past is used.

Prediction is a good word to describe this event because it is the automatic action that our associative brain does which can help us navigate quick enough through the world. By receiving unconscious perceptual input, we get a map of our world and our implicit knowledge can give us a good idea of what is present and what happens next. Attention is not necessary for this, but it does help to correct any errors.

Error Detection

Barrett describes how a brain which merely reacts to stimuli would be far too slow and that we need what we have learned in the past to work with incoming sensory data to predict what can happen next and turn our attention to the things which contradict that prediction.

For better or worse we learn to submerge much of our activities into the unconscious.

It is for better because otherwise we would live a few steps behind the world, so uncoordinated, like a baby, needing total concentration to move two muscles at once, and never getting used to our environment.

But it is for worse, because we can make mistaken assumptions of stability and not bring attention to an error in judgment. Our attention is lazy. For instance, when walking in your house with the lights off you can predict where the furniture is and usually you’re right, but stubbed toes are evidence that we are not perfect at this and that the slightest of changes can result in funny and painful events.

We need attention to correct for the errors of our associative, predicting unconscious.

For instance, when you are in a foreign city and walk past a group of strangers, and out of the corner of your eye, you see someone you recognize. Your attention goes straight to this person. You double-take. But awkwardly you see that this was not someone you knew, just another stranger. Attention in this case went to what was not predicted, i.e. seeing someone you knew in the foreign city.

Curiosity and Attention

We are born with an innate motivation to seek answers, to have an ever-wandering attention. We need to know things just in case. We need to live in stability of a predictable world. What is curiosity is a need to conceptualize, to make predictable for your next encounter with the object you seek out. For Martin Heidegger, this curiosity is a sin because it seeks to conceptualize what is not conceptualizable. It makes a being out of Being. We think that if we look long enough and gather enough facts, we can learn to never be surprised by anything.

The “curious” person learns things because they may be useful.

We are curious in this way not to encounter the unpredictable, but to extinguish it. When we research from this way of curiosity we are not trying to encounter some transcendent mystery, we are trying to break the mystery in pieces so that we can predict everything. And we can react easily and unconsciously. We ourselves try to become predictable.

Nothing is totally predictable on some level. Everything, every moment of experience, is in some way novel, and therefore might not be treated as stable. And that way, we can be curious about virtually anything.

The truly curious person for me, knows the limits of what we can predict. This is someone who learns things to be shocked, to be proven wrong and to discover Being and mystery. The truly curious person seeks to be surprised. And not surprised in a predictable sense, but in a totally new way. They do not want to visit a foreign land for a particular feeling of awe or culture, but to shock their worldview—they do not know what they will feel. They do not want to stop uncertainty but to augment it.

I think the best way to think about this is to be curious without expecting to come across a stability. And act like the world is stable so that you can be curious towards its instabilities. Paradox is a nice guide. There is so much chaos to appreciate in this world.