We concluded the last article by defining the problem of locating meaning in the first instances of biological life. While biological aims and patterns are present, they are not resolved by any positive ascent towards a telos. Instead, the aims of the material world are cyclical at best, chaotic and meaningless at worst. Looking at it from that perspective we cannot find any vertical axis for which cognition could be measured.

If we are going to attempt to understand cognition, we cannot remain here without an aim to biological life. Otherwise, all cognition remains justified because of its very existence as a naturally occurring process. All thought and behaviors would then be deemed true and permissible, since they fit causally in the physical world. That is the judge from the materialist perspective. If you are inclined to believe that is all there is, that all meaning is derived from material, you may stop reading now, there is no sense in studying cognition if you cannot assume a position where cognitive processes can be judged outside of their natural occurrences.

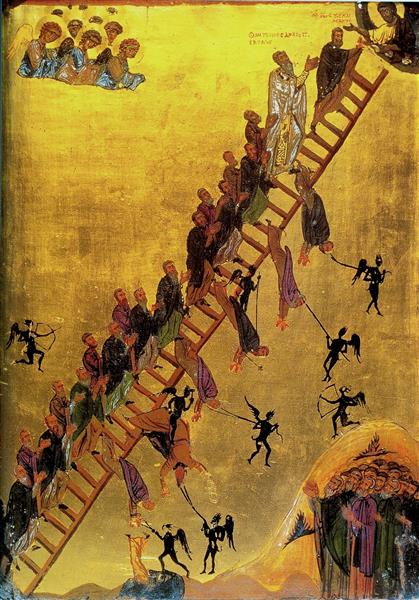

If, however, you have the intuition that perhaps there is something of cognition that can be judged as good or bad, right or wrong, despite both options having natural causes, then read on! In this essay we will attempt to reveal the vertical axis where cognition grows upward, where it has a goal, and can therefore be judged.

Nihilism in the Study of Nature

First, let us recap the problem so far. Life has uniqueness among other material things. It separates itself from the outer world through autopoietic processes that maintain that division through metabolic and self-organizing processes. This is the first instance of cognition and its mechanism of action. One could say that this process is the aim of all living things, for when this feature fails, the organism dies. That seems to be enough to judge what is right or wrong (what allows the life to go on); however, it becomes clear that no organisms are aimed fully at continual autopoietic existence. Rather, the organisms in existence today have depended on their reproductive potential, by replicating the organization of the organism rather than focusing fully on the longevity of the individual unit. So already, the role of cognition is extended past individual needs into the needs of preserving genetic identity.

That may also seem like an adequate end for biology to aim at: survive and proliferate. That is usually what people think of when they think of the goals of evolution. But we find that this is not an end in itself. The lineage of an organism cannot aim at merely creating identical replicas of itself. In a changing and chaotic environment, that is a recipe for failure. All of those identical copies will be equally unfamiliar to the changing environment, all equally uncoupled from its world. What gives life its resilience and ability to adapt, is the fact that organisms aim at producing diverse progeny, that both carry over its identity and change it as a meager way to predict the unpredictable future.

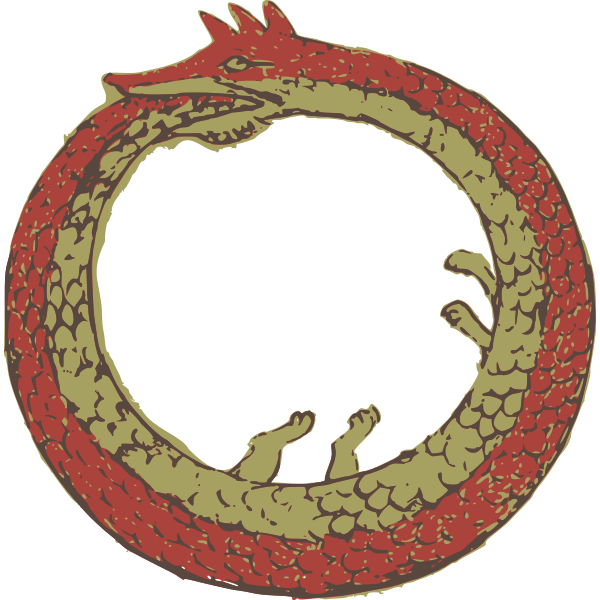

Thus our aims come back to original aim of survival; only now, the organism has acquired mutations which are potentially helpful but often burdensome to the process of autopoiesis. We have come to the snake biting its own tail: the processes that lead to prolonged existence, have the necessary feature of undermining its own ability to exist.

If we are to look at cognition at this level, it would seem that the organisms, by necessity, have traits that, because they are meant to predict the completely unpredictable, they are most likely to be maladaptations. Only at the population level does this play the odds and allow for the species to live on. The problem, if we are to judge cognition, is that we ought to judge in a way that allows nature to play itself out, that is, not to judge it at all. What we have is a morality based on what things tend to do, not of what they are aiming to do. The aim of life is what we are going to try defining here.

The Musical Metaphor for Potential Ascent

I once compared this cyclical process of evolution to be like that of an improvised song that goes on for as long as the lineage exists, and each variation on the musical theme is a generation in the lineage. Evolution of the song or species is conservative in that each musical iteration (a generation of the organism) necessarily bases itself off the previous ones, but also varies as a means for capturing the interest of the audience (or embodying a prediction of the future environment). Most variation to the unwise musician is random, and leads to the rejection of the song (extinction). But that randomness is essential, for nature (so far described) is like the unwise musician, it cannot predict ahead, and thus requires a lot of waste in order to produce something that survives, that pleases an audience of nature.

We need to add one more ingredient to the biological equation: the long passage of time. Then we may see the true ends for which biology seems to have an affinity towards. Nature, as with the musician, may have begun without wisdom, but surely can gain some after the passing thousands of generations. The musician we can imagine, would eventually pick up the rules that please the audience and apply them to the actual music he has been playing. This “knowledge” would be formed unconsciously at first, in a disordered fashion, but through time these repetitions become ordered according to the fixed laws of the audience relative to the song that is already being played.

The metaphor of the song is for getting us to see how progress is possible only if there is something more than material which guides it. In our imagination of the song, we cannot conceive of a song progressing in a positive direction on its own accord. It requires both a storehouse for intuitive learning and acting on the material of the song (the musician) and a judge that is governed by potentially intelligible patterns (the taste of the audience).

Can we see this same pattern with life and its environment?

Is there Wisdom in Life?

Let us first take for granted that there are indeed laws of nature that organisms honor in order to best survive, replicate, and adapt. That is easier to believe than there being some kind of “musician of life” which can derive ordered wisdom from unintelligible mutations. This musician is what we will look at first.

Consider how the function of the musician is to test out potentially good variations on the theme until one works. Even though many attempts do not rouse the audience, and some even risk ruining the song, the musician, if able to keep playing, gains some ability to order what works and hold back what doesn’t until a time it may work. As time passes, the ordering of the chaotic intuitions continues and the musician embodies more and more universal laws that govern the audience which manifests as the brilliance of the song.

Likewise, the organism accumulates latent and potential knowledge of the world through the generations of variations. This is represented best in DNA, in which most of its information seems disordered and useless, but when it becomes ordered it shows up as an adaptive trait. Like the unconscious mind of the musician, biological adaptation has to go through a chaotic accumulation before it can order itself in a way that is truly adaptive to its environment (both in mastery and resilience).

Life That Reflects Laws

If we can accept that there is something like a musician which contains the memory of the past generations and can convert it into adaptations that better reflect patterns of reality, we need to be able to accept that there is a true reality that is being reflected in the visible world and in living beings in particular. This reality, one should understand, is not visible, except perhaps only to the wise, to the perfect musician. I want us to come to this with humility and try not to say too much to soon about what the real patterns of reality are like. Perhaps, the best way to think of this is to entertain what the Christians believe about how God (the most eternal reality) is represented by all His creation. No one put it better than C.S. Lewis in his book Mere Christianity:

“Everything God has made has some likeness to Himself. Space is like Him in hugeness: not that the greatness of space is the same kind of greatness as God’s, but it is a sort of symbol of it, or a translation of it into non-spiritual terms. . . The intense activity and fertility of insects, for example, is a first dim resemblance to the unceasing activity and the creativeness of God. . . When we come to man, the highest of the animals, we get the completest resemblance to God which we know of.”

The material world is a reflection its creator, much like a novel reflects its author. The landscape reflects the authors mind some, but the characters even more. But biology has the special role of coming closer than inert material because life, like the musician, has the ability to embody the laws written by the great author, if only partly.

Judging Progress and the Grasping of Reality

If you find this argument convincing, do not quickly go using it as some tool to judge cognition according to what you think is reflective of reality. That would be too hasty; you have not learned anything about these eternal laws, except that humans embody them more closely than other animals. We have only begun to understand that there is a measure for which life can progress, but we do not know its mind.

When we look empirically at the world, we only see the representations of this wisdom. We see an isolated line of music which fits quite nicely to our ear, and we assume it was made from wisdom. But we do not know if we are listening to a Mozart who will consistently produce good music or if we are listening to a jingle writer who haphazardly creates a catchy line. We cannot directly derive the eternal reality from the representations of reality. We need a mediator; we need to know something about the musician.

Likewise, in Christianity, eternal reality is known through the perfect musician, the perfect embodiment of the eternal Creator. That is what is meant when Jesus said, “I am the way and the truth and the life. No one comes to the Father except through me. If you really know me, you will know my Father as well. From now on, you do know him and have seen him.” (John 14:5-7)

The journey from here is how life does progress in its embodiment of eternal reality. What we have said so far pertains to all living things if they are autopoietic, replicating, and adapting. We will next see how life grows in complexity to where it begins to unveil more and more of the nature of reality.