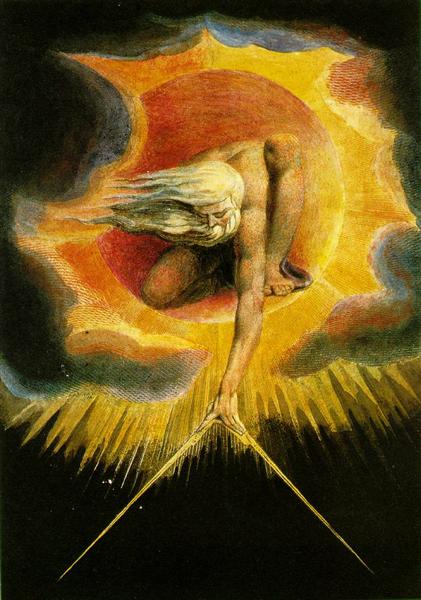

In the last article, we have argued for the potential for life to emerge into something with purpose rather than abiding by the mere rule of material existence (existence proceeding essence). Instead of meaningful phenomenon emerging from biology, a preexistent meaning is embodied in biology. Whereas materialism justifies anything by having a cause, proper embodiment is justified in its fidelity to the reflection of more eternal laws. Over long periods of evolutionary history, living organisms acquire traits that reflect the intelligence of the world, and the embodying of the eternal becomes the mode under which life retains its long-term material existence.

If I am going to claim that there is standard by which we can judge cognition, it is important to try defining that standard before we fall into incorrect assumptions. The question now becomes this: what does it look like when material, time-bound life reflects more and more eternal laws?

In the previous article we discussed the difficulty of identifying eternal truths among living things. It was compared to judging the overall genius of a musician by one song. Often a good song is representative of musical genius, but even a bad musician will eventually get lucky and randomly churn out a pleasant tune, one that fits his particular time and place, but few others, and is not repeatable. Likewise, any organism can have a spell of generations of well-adapted traits, but that may say very little about how well it conforms to eternal laws. When the environment inevitably changes, the genius of those traits is found to be a matter of luck only finding success in the narrowest of situations. Evolution continually is playing the odds, but out of that gambling comes patterns which begin to rely on more than luck.

Before describing what it means to embody more eternal truths, we must bring up the two temptations which we tend to imagine represent this aim. It will be a razors edge that we must walk.

Bias Towards Efficient Design and Over-Pruning

We have a bias towards living in a world where things make sense, have purpose, and clear functions. This is the world of the known, which is manifest spiritually as those truths that exist outside of the event or material itself. We have a tendency of believing the living examples of something are just pale reflections of what the essence of the thing is, which is defined by its purest function. This is nearly what I mean by embodying eternal patterns. However, we misunderstand this claim when we assume an existing thing is an accurate representation of the eternal reality. We do not consider that there could be disorder in the world which throws us off the sent of what is true.

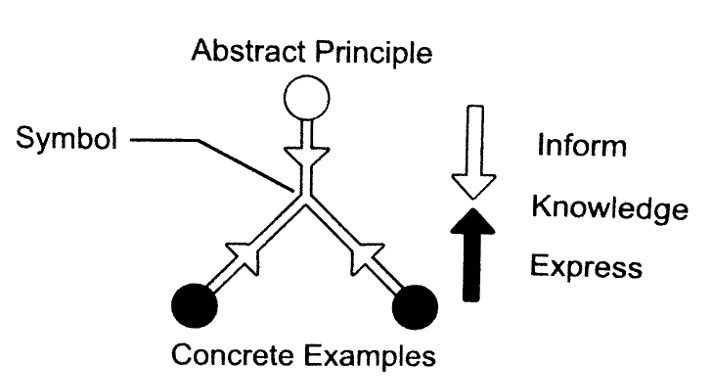

As we look at how well organisms are adapted to their environment and seem to master specific patterns, we abstract those qualities as potentially infinite and that what we see are merely shadows in comparison to the eternal and weightless spirit of that function or quality. The deception is when we assume a prideful knowledge of these functions, that these functions are built from the ground up and not rather the acting of the laws on the matter.

In analyzing the plant, the leaves convert solar energy for the plant, the roots gather the water, the flower attracts the pollinators. When we totalize these functions for each part, we attain a mindset of efficacy. If in this mindset, we would view the leaves lesser versions of solar panels which convert solar energy in a more straightforward and efficient way. The web of interconnected complexity falls away to reveal function, but the truth is not in the pure function.

The person deceived in this way desires to remove all inefficiencies of what he sees as machines since they are purer in their purposes. Machines reveal their purpose (their eternal spirit) more fully than the resilient, self-creating, but inefficient in a specific function, biological organism, because they are made by us for comprehendible reasons. It seems like the biological inefficiencies are impeding the reflection of eternal laws that the machine comes far closer to displaying. In farming, we see this quite often as farmers obsess with the eradication of pests, the exact calculations of fertilizer inputs, the pruning of all non-fruitbearing branches, the removal of all competition and “unnecessary” ecosystem. Our purpose is the fruit, even at the cost of the rest of the plant, and all the energy that is not directed towards that is wasted. The factory-izing of farming is attempt to build an “ecosystem” that is nothing but fruitful to its function.

The deception here is not that these ends are an illusion—the tree ought to aim for the fruit. Even if we correctly identify the aim, we are deceived by what it means to embody that function.

When we pridefully claim the purpose of our life according to the functions we perceive we have, all that does not fit, that slows it down, that is excessive, is discarded. In doing this we are forming a method of industrial agriculture on the soil of the soul. Without humility (from the term humus), we are compelled by the apparent perfection of our ends and become overly sensitive to the inefficiencies and distractions to the machine.

What was at first was making processes more efficient, became sacrificing potential adaptiveness and resilience. Then, in frustration it became the hatred of all that allows for that potential and resilience. We begin to hate the life in the soil, despite it being the foundation for plant growth. Likewise, our bodies become the obstacle to reason, even though reason is dependent on the body. Our goal should be to embody spiritual truth, not to become pure spirit. Even the most efficient machines do not conserve all energy. Always some is wasted in heat, by the material existence that makes the embodiment possible.

When answering a question on raising kids, Father Boniface Hicks responded with a gardening metaphor. He says raising a child is like growing a tree that one does not know the shape of. Sometimes parents tend to imagine what the full-grown tree will look like and prune it in that manner, when what we need to do is water the soil, create the potential. We assume we know the purpose of a life, and we severe other possibilities that we need for fully living.

Likewise, we ought to acknowledge that embodiment of the purposes of biological life requires a resilient foundation that is not apparently directed towards the aim, but it is the foundation for that aim.

Over-Emphasis on Potential

Since the first option strikes me as a narrow-minded mistake, I have quickly looked at what the opposite extreme might be. This one is harder to describe because there is really no analogous example, like in the case of a machine being aimed at a nearly perfect function. The closest thing is disordered matter itself. It is more difficult to come up with infinite potential without function other than the materialist view described in another article.

To move in the right direction from the “over-pruned” version of embodied truth, is to begin favoring of potential and resilience of that which could embody eternal reality. We start to see the wholesome, open, potent, and resilient ecosystem as essential to the greater purpose. No one can argue against the need to appreciate the wholistic vision of natural systems, but the problem comes when the emphasis on potential exceeds the need of the purpose. Rather than be overly selective in what is strictly relevant to embody a natural law, this worldview hopes for only the potential for embodiment: the organism in its ability to maintain autopoiesis, replicate, diversify. This is only the material potential for embodiment of the higher order, and we talked about it as a pointless cycle. This is to create fertile soil, but not attempt to grow anything in it. It is an oxymoron, a lazy Sisyphus, who instead of pushing the boulder, he rests in case he might have a call to push the boulder, which he would not listen to anyways.

Because, during the passing of time under the governance of particular and eternal laws, the pure potential is never fully realized, life has a tendency toward an order, even if that order is limited. The world is intelligible, and the eternal informs the temporal and material.

In practice, we err when we cannot see the transcendent, and without that higher purpose we allow the passions to do battle in the arena of the mind, not towards the highest good, but in the highest one at the moment.

This is how C.S. Lewis thought of faith. Faith for him is like holding to the power of reason even when the passions are momentarily shouting to override that reason. In Mere Christianity he says “Take a boy learning to swim. His reason knows perfectly well that an unsupported human body will not necessarily sink in water: he has seen dozens of people float and swim. But the whole question is whether he will be able to go on believing this when the instructor takes away his hand and leaves him unsupported in the water—or whether he will suddenly cease to believe it and get in a fright and go down.”

Aside from constructing lesser goods, this pattern has an anxiety-causing effect. If no instinct reigns supreme and the conflict remains, the situation is treated as totally novel and organism has no rudder for its action. That is the precondition for anxiety.

Complexity: The Dynamic of Efficiency and Resilient Potential

As humans, we either assume the highest good is within the world (and not as transcendent) and becomes the greatest good or the higher is rejected (or imagined to be unreachable) and the lower is raised up as a replacement. Both of these, which are generated by opposite mentalities, lead to the same outcome. Either we grasp for the good for our own or we raise up a statue to be our god. For the organism, it will either be well-adapted but with no potential for improvement or contain potential without well-ordered adaptations.

The reality is that both of these opposites contain truth but not at the expense of the other. There is a materiality that is constantly unique, defying category, so Heraclitus says that we cannot step into the same river twice. Because of this the organism needs to remain open and constantly doing what builds its potential and makes it resilient, the meaningless but materially vital things.

There are also laws that are transcendent, existing outside time one must embody to adapt to the world further through time. This is what allows the organism to ascend to more adaptive organizations.

The result of both of these looks like neither the efficient machine, nor that which deals with everything separately and uniquely. However, the organization that I describe as being both efficient in its mechanics and resilient to change, I call “complex.” That is not to be conflated with “complexity” meaning chaotic and difficult to understand, though complex systems often can appear that way to the untrained eye. By complexity here, I mean a structure ordered towards an aim that also accommodates the chaotic. In Biblical cosmology, this is the joining of Heaven and Earth.

The purpose of living things is in their conformation not merely to their specific environments, but to broader, slightly more eternal environments. It will master an element of nature, but it does so in a way that reaches down to the level of specificity and uniqueness. Embodiment of eternal realities takes on the form of a complex system, something only born out through the processes of life: complexity requires the chaotic maladaptations that get ordered to create an embodiment of meaning and matter. A thermometer measures temperature and water changes in reaction to temperature, but the temperature-regulated animal is the complex embodiment of the laws of temperature. The complex organism says something about the world by ordering the chaotic world towards acting according to the laws of nature.

A whimsical illustration of this paradox can be seen in J.R.R Tolkien’s character of Tom Bombadil. “The trees and the grasses and all things growing or living in the land belong each to themselves. Tom Bombadil is the Master.” In our use of the word Master, we end up thinking that all its subordinates are subject to his selfish and arbitrary will. However, in the definition we arrive at here is that all that is lower, unique, resisting definition, is mastered insofar as they are tended and allowed to have their uniqueness in service to the higher. Tom is master of the free and autonomous, but he is still Master. He endows his woods with his intelligence by embodying the eternal.

When we think of a manifestation of embodied truth, we should imagine something that, as it strives towards a universal and timeless aim, is adjusting itself according to particulars which do not fit so mechanically into the universal aim. And while it takes on the particulars it is able to order them into the greater schema of timeless laws. This truth is something that remains the same throughout time, but adapts to its specific environmental contexts.

“Know well the condition of your flocks, and give attention to your herds, for riches do not last forever; and does a crown endure all generations?” – Prov 27:23-24