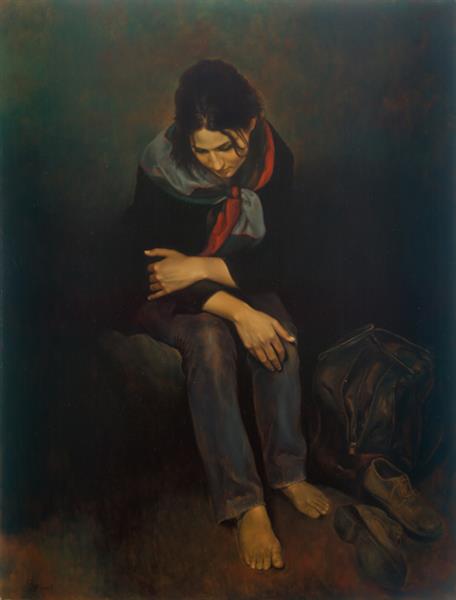

In troubling times, it is the uncertainty itself that seems to burden us the most. We wish, more than anything, that we could just know what will happen. Even if it is the worst outcome, we could at least be prepared. Sometimes we will act as if we are certain, because the alternative is so stressful and leads to no full commitment to action. There is no question of the role uncertainty plays in the anxieties of everyday life, but when it comes to our general understanding of the world, uncertainty is no less uncomfortable.

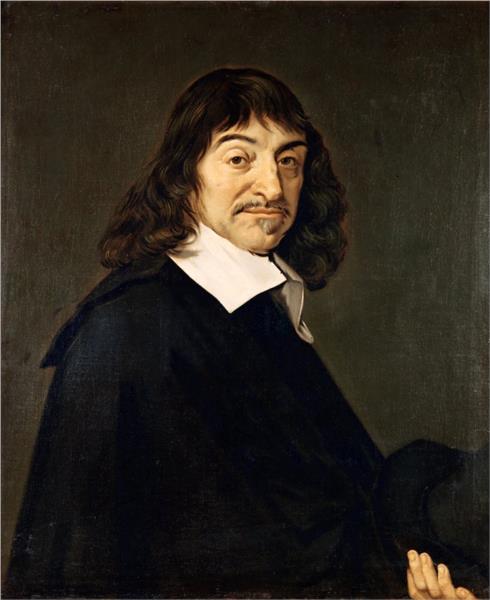

This stress of uncertainty causes us to come to hasty conclusions, shutting down arguments far too early. We then draw further conclusions from a hastily drawn premise, forcing us down a path of certain bias. Socrates and Descartes are philosophy’s most famous skeptics. They began their investigations with the attitude that they could prove nothing for certain. Socrates admitted that he knew nothing and made it his mission to expose those people who did claim wisdom as being just as ignorant. Descartes made pure skepticism a part of his philosophical method in order to start only from that which he was absolutely certain.

We can be grateful that skepticism can help us to challenge our presumptions, but pure skepticism is no ideal that we need to strive for. If we were satisfied with uncertainty, we may become unsure and timid in our actions.

“There is no more miserable human being than one in whom nothing is habitual but indecision, and for whom the lighting of every cigar, the drinking of every cup, the time of rising and going to bed every day, and the beginning of every bit of work, are subjects of express volitional deliberation.”

William James in Psychology: The Briefer Course

What attitude can we take towards knowledge that allows us to retain skepticism while also becoming more confident in one’s understanding of the world? Is it really a choice between a stressful, stupid honesty and an overconfident bliss? This dichotomy needs to be navigated consciously so that we can become confidently wise.

The Discomfort of Uncertainty

It is worth stressing that it is rather unnatural to reserve judgments—hence the stress that comes when we truly do. Naturally our mind wants to make assumptions so we can swiftly act on them. When we put off judgment until we have more information, we are working against our natural tendency.

We have to understand the difficulty of remaining uncertain, so we do not expect it to be easily accomplished. When we feel good about withholding judgment and allowing for uncertainty, we may be making other judgements that make it easier to deal with the uncertainty. We may say, “it doesn’t matter anyways,” to relieve ourselves of the need for understanding. To reserve judgement is to be in an unfinished state.

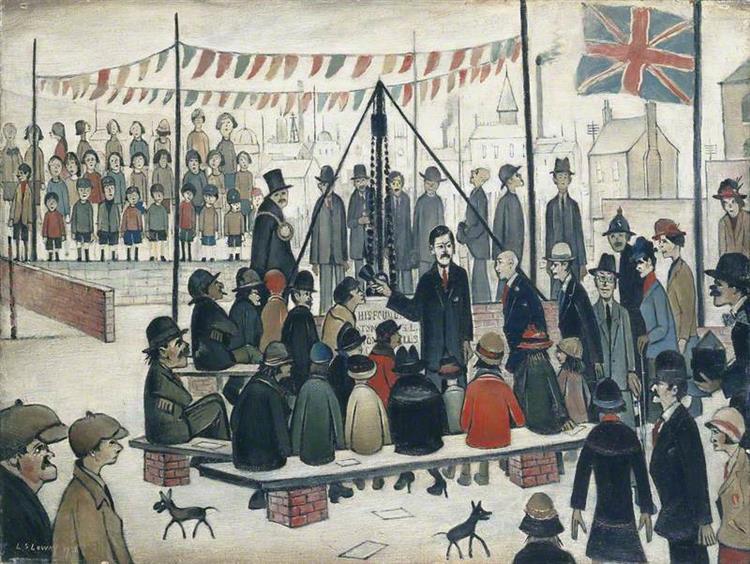

Uncertainty in times of struggle have obvious causes of stress—how to act and what to expect, for example. But when it comes to understanding the world, the stress of uncertainty is often compounded by our social pressures for certainty. It is harder to fit in when one is uncertain about a group consensus.

“We live in a culture where one of the greatest social disgraces is not having an opinion, so we often form our “opinions” based on superficial impressions or the borrowed ideas of others, without investing the time and thought that cultivating true conviction necessitates.”

Maria Popova in Brain Pickings

We Must Reserve Judgement

Why is it worth fighting against the need for certainty? After all, it is the desire for certainty that ignites our curiosity to look further into ourselves and our world. I do not want to disparage the need for certainty, but I do want to discourage the cheap methods of achieving it, or perhaps all notions of having achieved it.

We need some certainty to know how to immediately act and also as a starting place for greater understanding, but that should not keep us bound to having certainty. When we commit forever to a hastily drawn conclusion, we find ourselves on a path of ignorance.

“Doubt is an uncomfortable condition, but certainty is a ridiculous one.”

Attributed to Voltaire

Friedrich Nietzsche agrees that we have become far too arrogant when it comes to “intellect” and “truth.” He suggests we humble ourselves when it comes to Absolute Truth.

“The most firmly believed a priori “truths” are, for me—provisional assumptions, e.g., the law of causality, very well rehearsed habits of believing, so deeply incorporated that not believing them would drive the race to extinction. But are they for that reason truths? What a conclusion! As if the truth could be proved by man’s continuing to exist!”

Friedrich Nietzsche in On Truth and Untruth

Even the most obvious truths which we hold, are held because of their practicality, not their absolute certainty. It may be that the law of causation is close enough to Truth that it would be silly to act uncertain of it, but when it comes to the more ambiguous truths we claim to know, we find it even harder to justify certainty.

The problem with acting one or claiming full certainty on a “truth” is that we then feel confident interpreting experiences through that truth, justifying, and strengthening the poorly thought-out premise. That certainty can then become even more emotional than before, because so many meaningful conclusions have been stacked on top of it.

This happens early in our lives and without our awareness. It is culture and upbringing that give us the deep assumptions about our life that we will almost never become skeptical of, if we can even articulate them. It is not assumptions of the layperson’s understanding laws of physics that are most needed to reserve judgments on perhaps, but it is those assumptions of how relationships, life, and oneself are and ought to be in the world. It is those which may be the best to become uncertain of and come to know as “provisional assumptions.”

Acting and Gaining Understanding without Certainty

Not only is acting impossible without accepting some certainty of the situation, but our complex understanding of things is predicated on making some provisional assumptions. The problem with extreme skepticism is that we can never simultaneously hold that skeptical attitude and build a large amount of understanding. We would be stuck at zero in terms of understanding complex things since we would not accept even the most basic premises. Our core beliefs support so much more of our knowledge, that it would be traumatic if we were forced to doubt them.

The world, as we undoubtedly know, is complex, and there is no way of understanding this complexity without having some faith in some fundamental provisional assumptions. For instance, we cannot talk about anything in moral philosophy without first assuming that others exist with their own experiences. If everyone were the philosophical “zombies,” debate on morality and ethics would be obsolete.

Science works much like this. Scientists rely on other pieces of evidence to support their theories. It they come close enough to a certain proposition, they can continue adding complexity to the newly understood theory.

“A scientist, faced with evidence supporting a theory, evidence acknowledged not to be completely decisive, may choose to accept the theory or not to accept it. If the theory is accepted, the scientist ceases inquiring into its truth and becomes willing to ground her own research and interpretations in that theory; the contrary if the theory is not accepted.”

Eric Schwitzgebel in the Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy article “Belief”

How to Truly Reserve Judgement

Belief, at its base, is to cease inquiring about the question and move on. Building on a “provisional assumption” may be just as much belief as the one who considers their belief to be inarguably truth. For that reason, we have to careful not to assert false skepticism. We cannot claim to be skeptical of something that our other beliefs are hinged upon.

“The skeptic still continues to reason and believe, even though he asserts that he cannot defend his reason by reason.”

David Hume

What happens with this skeptic that David Hume talks about is that he reserves judgement on a basic belief, but continues to construct more and more ideas based upon that belief.

Instead of claiming pure skepticism, we can claim our beliefs are “provisional assumptions” which adjust themselves to the evidence. Not that they are any final truth, but that they seem to be the best one available to us until more evidence changes or disproves them.

“Reasonable faith arguably needs to conform to an evidentialist principle, generally thought essential to rationality, requiring belief commitments to accord with the extent of the support for their truth given by one’s total available evidence.”

John Bishop in the Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy article “Faith”

This is not a theory of epistemology but an idea which support a need for openness to the world. This is for us to cultivate a reasonable faith. We cannot find any perfectly settled conclusions, although we will have to settle on them when we must act urgently.

For example, when stuck on a Sudoku puzzle, you may be tempted to take a 50/50 guess—a provisional assumption. Since there is obvious uncertainty in this guess, you try to remember all the moves you make which are only accurate according to the uncertain guess. If you find an error, you must know where you made a faulty presumption. This I think can and should be applied to our attitude in beliefs.

If we become conscious of our assumptions and the further reasoning predicated on that assumption, we will be resilient when evidence given to challenge those assumptions. With this, I can offer three pieces of advice.

To become aware of our assumptions, one must look at their results. Becoming aware of our emotions can tell us what we expect from others and ourselves. All of our conscious expressions of belief are rooted in archetypal and foundational beliefs or assumptions. Any of these can be challenged—dichotomies exist, shadow archetypes oppose, and alternative views have purpose. Become perceptive in one’s thoughts and the patterns which arise in one’s life which may suggest a foundational belief.

Once we are aware of some of our assumptions, we should look for evidence of alternatives to them. This will help broaden the assumption and give us the ability to complexly interpret our experiences. But this testing out of new views should be just as provisional as the belief before it. It is common for us to fall in love with a novel way of looking at things. One should be aware of this. Ultimately the goal here is not be believe something different but to begin understanding how what appears to be a dichotomy in belief can become unified and both sides can be used to interpret the same things.

The final piece of advice is to take this process slowly. To undermine one’s foundational beliefs is traumatic. It shatters what one used to know, and one is bound to lose the past completely if change is too sudden. The distaste for the ignorance one’s past self is evidence of this. To change and grow one’s understanding is to experience small and unnoticeable “traumas” to our assumption over a long period of time by allowing for uncertainty in those deep assumptions (i.e., accommodation). We are not doing this because our assumptions are bad, but that they are missing alternative possibilities. This takes years and a lifetime to mature, and rushing it only stunts growth.