Getting at the core of our experience is difficult to do philosophically, and for good reason, there is little written by authors who are experiencing first-hand the creation of the self: infants. It is a constant danger when talking about this age that one will start going off on mere speculation. However, I will risk that possibility to convey ideas born out of psychoanalysis about this delicate time. Here, I will try to describe the beginning of one of the first conflicts in our personal histories.

The conflict begins in the first instances of infantile dissatisfaction. Here, we look at two differing perspectives, which seem opposing, but in the end, have more complementary positions. How is deprivation involved in the creation of the conscious, autonomous ego?

As we age, we develop new “natures” of habits and our relationship to those habits is part of what makes human life so complex. This early stage lays down a foundation of our attitudes toward our own natures. We come to understand that this stage sets us up to be intentional in the world, rather than trusting of our “nature” or habits.

To Deprive or Not to Deprive, Is that the Question?

An idea which seems very radical was given by Sigmund Freud that deprivation for a child is precisely what he or she needs. Of course, this sounds ridiculous when phrased provocatively, but the point is far more subtle. Although Freud understood the necessity of early nurturing of infants, he also believed that there would be no reason for a child to grow up if all the child’s needs were met before the child was even aware of what those needs were. In this hypothetical “Golden Age” of anticipatory satisfaction, infancy could be extended indefinitely. However, no mortal parent can give that to their child, regardless of their devotion to perfection.

“This slow, incremental failure of the mother to “bring the world” to the baby has a powerful, somewhat painful, but constructive impact on his experience. He slowly begins to realize, in the gradually widening gap between desire and satisfaction, that contrary to his plausible and compelling earlier beliefs, his desires are not omnipotent… the infant . . . begins to feel dependent for the first time. There is a gradual awareness that the world consists not of one subjectivity, but of many; that satisfaction of one’s desires requires not merely their expression but negotiations with other persons, who have their own desires and agendas.”

Mitchell & Black

The point is of course, not that neglect of infants is a good style of parenting, but that the inevitable failure of perfect mothering is a necessary part of childhood development. The extremes of overprotection should be resisted, so that a parent can be “good enough” rather than perfect, as Winnicott preferred to phrase it. It is the failure of being the perfect mother, that allows further development of the child. Freud is certainly not alone in this theory.

“The process of development entails many moments of discomfort and frustration. Indeed, some frustration of the infant’s wants by the caretaker’s separate comings and goings is essential to development – for if everything were always simply given in advance of discomfort, the child would never try out its own projects of control.”

Martha Nussbaum

However, with caution, I will qualify this theory with its complement. René Spitz seemed to have a damning counterargument to Freud’s. He studied infants that were abandoned essentially in an orphanage where their physical needs were met by the staff, but despite that, many died, and the rest developed major emotional problems. René Spitz suggests that deprivation particularly of holding promotes fantasy and disengagement with reality. This disagreement is written about in detail in Freud and Beyond by Stephen Mitchell and Margaret Black.

These apparently contradictory theories are not contradictory at all. They describe deprivation in two very different parts of life, despite it being generally in the same period of time. We need to consider is the readiness for such a deprivation and the meaning that it gives the child in its multiple forms. Let me attempt to illustrate the world of the infant to resolve this conflict.

Holding and Creating Ego-Consciousness

This situation occurs in infancy where, in our first six months, we are practically at the mercy of our reflexes and the interaction of those reflexes with our caregiver. Our nature guides us entirely, hopefully towards a positive relationship with the mother/world. But soon we come to realize that nature fails to fill the need before it becomes conscious. Further, there become longer delays between discomfort and relief. Now comes the challenge to the infant. What one “knows” must be retooled. One’s nature may need a higher guiding principle.

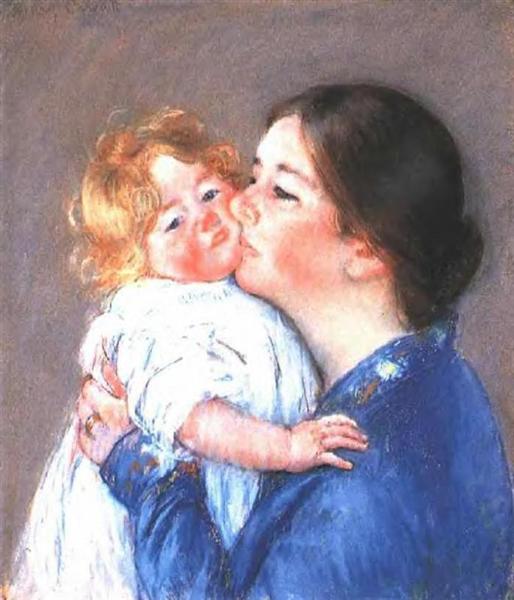

Clearly being nurtured is a requirement of any infant, no one really argues that. Looking at the work of John Bowlby and Harry Harlow show us that physical contact with the infant should be categorized as a need for survival, not a bonus. But what is this holding doing for the child, and when is it too much?

In a time where so much is unknown and disjointed, the infant needs to have a place where things make sense, where needs are met before they arise, where its nature can operate without conflict. This is often called a holding environment. This is the outcome of a successful outcome of the basic-trust-versus-mistrust phase of Erik Erikson. This allows one to, even in bad or chaotic moments, the infant will always be returned to that secure place of holding and ease. This provides the ground on which the ego-consciousness, the primordial narrative of the child can grow in trust and stability.

The ego is what signifies, to the infant, the infant’s relationship to the world. This trust gives the infant a feeling of omnipotence in relation to the world. As far as any story can be articulated, it is a story of being the emperor of a Golden Age. Where there is nothing but indulgence. Occasionally the utopia will disappear, but often, it will come back. This is the holding environment of the first developmental journey, the infant knows, that no matter what, there will always be a rescuer or its own nature to bring back the bliss.

The Call: A Growing Gap Between Desire and Fulfillment

There is but a problem, as with all apparent utopias. Slowly the gap between each blissful moment grows wider. The parents leave the child alone for longer, the age of the infant means that the usual nursing and holding will not always suffice, not to mention the infant’s teething. As the infant grows its senses see further, as its motor skills begin to resemble intentional action, its nature changes. What was an effortless emersion into perfect bliss has now become less and less possible to replicate. That story of inevitable returns to bliss, is now inadequate for the child’s operations.

The infant can now see that the physical mother as an object among many has been the cause of such blissful rescues, and that many times one’s actions have elicited that response. The new story is that ordered intention and attention can bring about and prolong bliss, but also that there are outside forces that disrupt the bliss.

These new problems help the infant realize that the moments of deprivation require something other than reflex. This newly required skill is the use of intention. The situation starts to take on more objects in the world, but it also replaces reflex with impulse as how the infant sees its relationship. Impulse is a close relative to reflex but has acquired objects as their aims. Impulse requires the conscious recognition of a deprivation, it has the aim of filling that need.

This idea is mythologized as a call to adventure of hero’s journey. From a place of comfort, the infant is called to the information that that comfort is gone, and to reclaim it, one must endure unknown lands, such as the outcomes of acting on intentional impulses.

What the overprotective mother does to thwart this ego development. Is to continue provide the child with the bliss of holding before the infant feels the deprivation and before the infant must communicate with intention. If this is done after the infant has achieved trust in its environment, this will become like a barrier for impulse rather than the bliss it once was. This can cause runaway positive reinforcement problems such as restrictive holding where the child cannot communicate and the default is holding, perhaps when the child needs something else. This is what happens when an infant cannot exercise its “projects of control.”

On the flipside, this call can be made without the infant having the original trust of the holding environment, but the distress would not be understood as a call to reclaim bliss, as it would be for another infant. Like the orphans Spitz observed, an infant might not have the ability to differentiate the widening gap of deprivation that calls forth impulse from the undifferentiated chaos of life without being held. There was no sense that one’s nature was to be trusted, and the impulse that may come from deprivation may have no object. One does not have that blissful, trusting, relationship in which one can then stride to restore, only a need without solution. They may choose to disengage with the deprivation, because they reject its discomfort, but feel nothing compelling to move towards.

Our Present Non-gratification

Although this stage is practically ancient to us, it is not inconsequential. On the contrary, its effects are wide reaching but hardly detectable in the very fabric of our self-narratives. We are still affected by the way we react to the non-gratification patterns laid down in infancy. The major difference between now and then is that instead of the infantile reflexes, we have instinct and habit patterns which we depend on. These interact with our environments before we become aware of our dissatisfactions. A clear example is we eat before we are hungry, because we have a habit of eating, because our nature solves the problem before we need the conscious discomfort.

Consider that, even known, or imagination of heaven is something like the blissful “Golden Age” of early infancy. That is how we think of our bliss, as being where habit and instinct takes care of every problem. Consciousness is too burdensome. We do consider heaven as a place of constant updating to our habits to their outcomes. To achieve glimpses of unconscious bliss, we are willing to risk other outcomes, and we stop paying attention to the outcomes (a well-documented phenomenon of habit). This system operates without intention. Intention looks for outcomes, habit and nature simply follow orders.

Giving space between our reflexive actions and their satisfaction is not a discovery made by Freud, although that is an outcome of his thinking. One does not have to look far to see that Eastern practices use the concept of non-reactivity which allows one’s nature to come to consciousness. And I have written about it from a cognitive standpoint. When we sit, nongratified, we open a gap where consciousness can come in discovering the object to which we might aim.

“Nongratification (e.g., not answering the patient’s questions) and interpretive confrontations were aimed at forcing the id-generated fantasies to seek gratification out in the open, exposing them to conscious scrutiny and analytic interpretation, thereby transforming them into more realistic, mature ways of thinking, generating increased ego functioning.”

Mitchell & Black

We stop living intentionally because part of us wants to return to the bliss of being soothed and being one with nature. However, we can only go back to that until we have perfected our natures (we cannot go back). But we can get close to a return, it is a long road, it requires many evolutions, and it lasts a lifetime.