In the ambitious effort to grasp at the Truth by means of understanding psychology, I want to first describe cognition as it emerged from early biological phenomena. In doing so, we can see what is fundamental about what it means to be thinking beings. However, this method too easily gives the impression that cognition is reduced to a mere result of biological processes. To remedy this error and others like it, we must posit an outline foundation of reality. In this article, I present one of the great conundrums of philosophy and use it to flag off the trap of materialism that we tend to fall into. That conundrum is the mystery of consciousness.

In today’s scientifically informed world, we have a fractured view of the foundation of reality. In one sense we believe that reality is a place of material things and physical properties, where biological, and therefore psychological, life can be explained by the emergence of patterns and accidents of an otherwise dead world. This has produced much spiritual turmoil by taking what is perceived as significant and placing it in a world of neutrality and happenstance which we proudly call “objective.” Yet, in spite of our scientific enlightenment, all of our belief comes through a mode of meaning and significance, antithetical to the neutrality of objective “things.” This issue needs to be addressed from the beginning, because if we cannot keep in mind the mystery of consciousness, we will fall into further misunderstandings.

In the first part of this article, I define what creates the tension of the problem of pitting mind against matter, particularly when mind is discarded. The second part, is an exercise in illustrating how serious this problem is in our lives. In the final section, I hint at the solution which has been long-ignored in today’s academic environment as a means of reconciling a reality of minds.

Our Current State of Materialism and Meaninglessness

In the past couple centuries, the notion that life has a real purpose or meaning has been under assault. Scientific methodologies, which require removing one’s particular perspective, seems not only to have shed light on many mysteries of the physical realm, but it also seems to promise that all mysteries, including spiritual ones, will one day be fully understood in the light of the empirical scientific process.

The assumption that the world can be observed from a neutral perspective has had great utility in perceiving the biases and misperceptions that come with our psychological limitations. While growing in our understanding of natural processes is good, our assumption that nature is the only real thing is a costly one. This view I will call materialism; however, it is also called “physicalism” or “naturalism” in philosophical circles.

Materialism, rather than being an outcome of good science, is an overgeneralization of the utility of empirical science; it is more of a philosophical position than a conclusion that follows from science. Scientists, in their work, say “let us for the moment distrust our perceptions and intuitions, so that we may understand how nature works independently of our meaning.” The materialists then see the mighty work of science and presume that the lens scientists look through is a lens on all of reality. Materialism is a removal of meaning, not as a tool for understanding physical processes, but as a way of seeing everything.

When we explain phenomena only according to their physical, material causes; everything then appears as a mere effect of a physical cause, and, by nature of having only an objective cause, is meaningless. We can even now study the brain as it “makes meaning,” and so we can explain meaning itself by its physical causes. We then see all organisms, including ourselves, as Richard Dawkins does, as the container for “selfish genes” which exist for the sake of existence and no other purpose. So long as we can explain meaningful things with a physical cause, we’ve reduced its meaning to a mechanical phenomenon.

Although this seems like the default result of scientific progress, materialism ignores evidence of “something” outside the purview of materialism.

The Hard Problem of Consciousness

Let’s assume the starting position that reality is merely material, that a dead world gave rise to things which only seem as if there is life and meaning. What anomalies can we not account for with this view? And are they significant enough to undermine it?

In fact, what this position cannot explain stares us right in the face: consciousness. By consciousness here I do not yet mean the self-reflectiveness sort, but a more primordial being-ness, that there is something it is like to be me, just as there is something it is like to be you. Simply put, there are points of subjectivity in the material world. All further definitions of consciousness presume this and build off this basic fact.

This is what David Chalmers calls the “hard problem of consciousness.” This “hard problem” describes the situation where philosophers of mind have struggled to place the existence of minds into the materialist framework. While we can peer from the outside at every physical correlate of consciousness, we seem to get no closer to seeing what it is actually like from the inside.

The Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy article on “Qualia” says,

“For no matter how deeply we probe into the physical structure of neurons and the chemical transactions which occur when they fire, no matter how much objective information we come to acquire, we still seem to be left with something that we cannot explain, namely, why and how such-and-such objective, physical changes, whatever they might be, generate so-and-so subjective feeling, or any subjective feeling at all.”

Philosopher Thomas Nagel famously wrote the article “What It Is Like to Be a Bat” arguing that no one can have truly participatory knowledge from the point of view of a bat. We can only infer from how our own analogous experiences would operate with what we know of the sensorimotor organs of the bat. Especially because bats have such a uniquely different perceptual structure (echolocation, for instance) and value system, we truly have no basis for imagining how the world is experienced by the bat. We can only observe bats as a part of our world and analogize that into our experience.

This is also true even of other humans. Empathy is a natural ability for people to analogize emotions of another person into themselves. While with it we get close to knowing what it is like to be another person, empathy is imperfect because you only indirectly and incompletely know what they feel as you experience them in your world.

By the fact and mystery of consciousness, we know that there are real phenomena that are by their very nature, unobservable. So how can we still continue to justify materialism today?

Epiphenomenalism and Inventing the Absurd

What should be apparent to everyone who is vaguely aware of neuroscience is that mental states are contingent with physical states. When physical brain states are induced, the subject reports mental changes. We then infer that the physical world is what gives rise to the nonphysical world. This is sensible.

We can also see that when simpler parts are combined in complex ways, it gives rise to new phenomena. You need enough mass for a star to ignite; you need all the necessary parts of your phone to coordinate in order to make a call; hydrogen and oxygen atoms have nothing watery about them, but when they are ordered in a certain way, a watery property emerges. Likewise, we can infer that nervous tissue, once it reaches a certain level of complexity, will produce the previously non-existent phenomenon of consciousness.

Combining those two premises we get a view of consciousness that is typically called epiphenomenalism, which is the understanding of consciousness as an emergent phenomenon totally dependent on states and complexity of matter. There are two routes for where the epiphenomenalist then will go to explain consciousness away to support a belief where materialism is the dominant reality, and consciousness an anomalous off-shoot not to be taken seriously.

The first is to claim consciousness is impotent, nonfunctional. Because this view holds that since the direction of causality is from physical to nonphysical, the emergence of consciousness has no effect on the physical. This is purported to be backed up by research that finds out that consciousness is not required for actions that were previously thought to require it. Julian Jaynes summarizes these in his book The Origin of Consciousness in the Breakdown of the Bicameral Mind. Consciousness is ignored as an anomaly because it has no obvious effect in the world. We are then helpless spectators, falsely imagining meaning in a world which is utterly indifferent.

While the materialist uses consciousness’s apparent lack of physical function to fit his worldview, he does so by creating a far stranger belief than even the Christian. Apparently, indifferent material seemed to, in some sort of fluke, form itself into meaning-making observers of itself. It almost requires a religion to hold the view that a meaningless material somehow felt the needs to show off its meaninglessness by putting totally ineffective subjective viewers in it. Truly, if consciousness does not have a meaningful function, it should be perfectly reasonable for material nature to have got on just fine without putting minds into the bodies of its creatures.

If, on the other hand, consciousness does have a function which could explain why it evolved, we have another problem for the materialist to deal with. What sort of ecological niche would the adaptation of embodied subjective minds body have adapted to? What selection pressures required conscious observers and not automatons? Could that environment be merely physical? How then would non-material consciousness have any effect in it?

“Each living creature must be looked at as a microcosm—a little universe, formed of a host of self propagating organisms, inconceivably minute and numerous as the stars in heaven” – Charles Darwin

If we look at a conscious being as a microcosm adapted by evolution to its environment, should we not guess that reality contains something for consciousness to be adapted for? If reality where not merely material but also informational, in which it contained both the sender of information and the mind-like thing to receive it, we could understand how minds exist alongside matter. Then like the wings of a bird correspond to the aerodynamics of the skies, the mind of man corresponds to the spirituality of the cosmos, the potency of the world for meaning. Perhaps consciousness doesn’t exist in spite of a meaningless world, but it exists because meaning is within reality to be witnessed by minds. From this argument we see that consciousness poses a real threat to both a hard materialism and its softer version of epiphenomenalism. Now, we will look at how materialism gets played out in practice.

The Spirituality of Pseudo-Materialism

Putting aside the more philosophical arguments, we come to the practical reality in which the materialist must live. The materialist, like all of us, is convicted by his experience of the world; he has to act according to the pains and pleasures and meanings of life. But while acting according to implicit values, he will intellectually tell himself that everything comes to nothing. If pressed, the materialist would have to say all of his perceptions and desires are meaningless. It may even be veiled in a sophisticated way by appealing to biological evolution as the cause of his values. But that is just a way of saying, “I only value these things because I have been programed to by a meaningless reality.” All we experience is through some kind of false screen.

“My soul had for a long time now been used to seeing in nature nothing but a dead desert covered by a veil of beauty, worn by nature like a mask that deceives.” – Sergei Bulgakov

The archetype of how to live as a materialist is found in Sisyphus, an ancient character doomed for eternity to push a boulder up a hill only for it to roll back down. One could say at this point that, like Sisyphus, we must get over our need for higher meaning and just accept the lesser meanings in life so as to tolerate our suffering. I have been quite fond of this attitude myself. It fit my agnostic yet hopeful sensibilities: there is something tragically heroic about fighting the slow defeat into chaos. Creating meaning for oneself to tolerate the difficulties of life seems like the only option if reality is truly a meaningless place that forces us to live in meaningful relationship with it.

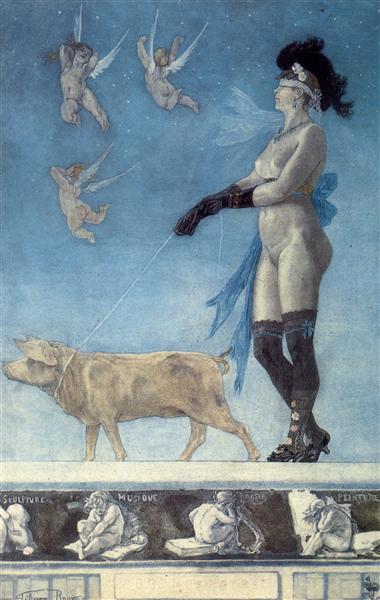

However, this idea does not come as a result of mature realism and philosophy; it is an ancient and intuitive idea. The idea of death as the end of meaning has always been on the minds of ancient people. For someone to use superficial meaning to tolerate a backdrop of superordinate disorder is the cosmological sibling of the way the ancient pagans would have perceived their world. Their gods were those values worth appeasing or negotiating with in order to keep one safe from the chaos beyond. Since the seat of the supreme god was always up for grabs, the pagans realized that value systems did not have stable foundations, they were just temporary ways of tolerating what would eventually amount to nothing.

Materialism, Taken Seriously

Materialism is not the purely objective belief that life is ultimately meaningless; rather ironically, it is when the very thing that makes meaning, proposes the futility of meaning, and rejects its own existence. For this reason, materialism results not in enlightenment at seeing truth, but in depression where meaninglessness itself has meaningful effects. As biologist Christian de Duve put it, materialists are effectively saying, “truth is important as long as we don’t know or believe it.”

Again, our hero here is Sisyphus who continues to push his boulder up the hill only to have it roll down the other side; apparently, he can deceive himself enough in the task to continue his labor. However, we are not Sisyphus, and when we truly encounter the futility of our suffering, we do not continue with the effort. We should desire nothing more than to avoid all effort or kill the thing that makes possible to receive the suffering. That “thing” is consciousness in its function of creating and perceiving meaning.

Distractions, habits, pleasures, and other infantile or animalistic impulses put to sleep that part of us that had identified the need for meaning. We immerse ourselves into projects to maintain our attention, we seek spectacles on screens, the pleasures of food and drink, the promises of scrolling of social media, the self-centered pleasures of sex and lustful imagination, the obsession of sports, gossip, politics, and the affairs of people we will never meet. What are these but the temporary relief from the awareness of a meaningless existence.

In this mode, we do not believe in a reality of meaning, except insofar as it can dull the fact of meaninglessness. In its theological understanding you are negotiating with a god to repel back the forces of chaos. Nothing is eternal except the chaos; nothing is truly desired except what has promised to stave off the meaninglessness.

Some of the ways we avoid our suffering can appear as if they are undertaken by highly desirous people, but this is a mistake in perception. Often, we are highly motivated to avoid the reality of death, which is not an excess of desire but a lack of it. C.S. Lewis puts it best.

“It would seem that Our Lord finds our desires not too strong, but too weak. We are half-hearted creatures, fooling about with drink and sex and ambition when infinite joy is offered us, like an ignorant child who wants to go on making mud pies in a slum because he cannot imagine what is meant by the offer of a holiday at the sea. We are far too easily pleased.”

Because our world is not here to cater to our simple pleasures, it will eventually deprive us even of our distractions. Sickness, death, hunger, poverty, and disenchantment with carnal and egotist pursuits reveal the deception of our false gods. We will eventually be naked in front of the dragon of chaos, at which point there is only one thing left that can promise escape and we ask, “why shouldn’t death come sooner?”

Our hero Sisyphus, goes from noble to hopeless. In The Lord of the Rings the despairing steward Denethor says, “Battle is vain. Why should we wish to live longer? Why should we not go to death side by side? [. . .] For thy hope is but ignorance. Go then and labour in healing! Go forth and fight! Vanity. For a little space you may triumph on the field, for a day. But against the Power that now arises there is no victory.” Truly the anthem of the materialist: thy hope is but ignorance.

A Society of Materialism

Not only has this materialism eroded the personal sense of meaning, causing strife for the individual, but it has become the religion of the modern affluent world. The moment something is taken seriously and we seem at first willing to suffer for it, we are reminded how it does not really matter. Since suffering cannot be meaningful in this life, we should look to occupy ourselves with something less serious that we could freely discard when it ceases to satisfy. When a society takes on this religion its takes on a new form. This cultural pattern of apathy has been detected for over 100 years as evidenced by G.K. Chesterton’s observation of the same pattern in his day.

“A man’s opinion on tramcars matters; his opinion on Botticelli matters; his opinion on all things does not matter. He may turn over and explore a million objects, but he must not find that strange object, the universe; for if he does this he will have a religion and be lost. Everything matters—except everything.”

and

“When the old Liberals removed the gags from all the heresies, their idea was that religious and philosophical discoveries might thus be made. Their view was that cosmic truth was so important that every one ought to bear independent testimony. The modern idea is that cosmic truth is so unimportant that it cannot matter what any one says.”

Though we think we’ve gained control of meaning in our lives by making it a tool to be thrown out when it no longer serves, truly, we have become enslaved to those fleeting things. By making the peripheral things into the central hope, we’ve committed ourselves to following every whim of our desires. The scent and promise of freedom pull us into the cage of our own self-gratification. Again, Chesterton offers his wisdom:

“The moment sex ceases to be a servant it becomes a tyrant.”

Soon the “atheist” will look like the religious one. However, we have now left the realm of materialism to find its sibling: tyranny. This will be a discussion for the next article. For now, we should realize that these two, nihilism and tyranny, are always working together. One cannot function in believing in a meaningless world without the world tempting one into a servile role towards whatever promises to relieve the meaningless “reality.”

Reckoning with Minds

Materialism, when taken seriously as an idea, cannot remain consistent, because in its very observation of a lack of meaning, a yearning for meaning is experienced. The consequences, as earlier described, are spiritually devastating. However, I do not mean to disprove materialism as a reality just because we, as limited biological creatures, cannot hold to it perfectly or because attempting to do so has negative consequences. Truth might be difficult to swallow. Though the pragmatic reason to deny materialism should be taken seriously, we can also look at it from a more metaphysical perspective.

Materialism posits a world where the measure of reality is in whether or not objects interact with other objects, and can theoretically be observed scientifically. What is real must have potentially detectable effects. So, if we were to posit something that has no clear effect in the material world, the materialist would consider it as good as non-existent. Consciousness is such a “thing.” Though it is the foundation of all observation, it itself is not observed directly as if a part of the physical world. This suggests that, although consciousness seems to be embodied in physical phenomena, it is of a totally different nature, one unaccounted for in materialism. And for that reason, we should grant a reality which not only includes the seen and observable but also the unseen yet somehow experienceable.

Why should we make a big deal out of something that produces no observable effects? Should we treat it as an isolated anomaly and not come to any conclusions regarding a non-physical reality? Should we place trust in something that will not give us physical evidence to prove itself? If we do accept it, how do we understand it without the empirical methods we have grown accustomed to using? These are the questions flowing from the “hard problem of consciousness.” But rather than get stuck at these impossible questions, we can open ourselves up to the mystery of consciousness, that ineffability and transcendence is our reality as much so as the physical realm. While science provides an epistemology for the observable material world, we need an epistemology for how we understand that which is not observable.

While “faith” as a way of knowing the world may have some of us rolling our eyes, we need to look to a kind of faith as a way of knowing the unobservable and ineffable. Let’s take an example of faith that we know is reasonable: other people have minds and experiences somewhat analogous to our own. Try proving it empirically and you fail, so why do you still believe it?

The “proof” that we have of other minds may be summed up as the subjectively meaningful projections we make onto the bodies of other people. When we experience meaning in our lives, it is because we posit something other which can observe our actions. Meaning does not come from some satisfying some isolated impulse from within. Think of a child who may act hedonistically when alone, but in the presence of a parent, he sees himself being observed by another authority and orients himself towards another good. As we mature, this gets more complex, yet the principle is the same. If we were to experience the world as if there was no one observing us, our actions would have no significance beyond the merely biological. We do not manufacture our own meaning; we experience it as the perception of other minds. It is by faith that we believe meaning signify something real in the world that we cannot physically observe but that we recognize as another’s presence as a conscious being.

“Faith is not an isolated act. No one can believe alone, just as no one can live alone. You have not given yourself faith as you have not given yourself life.” (CCC 166)

I say that observing minds is a “projection” of meaning onto the observable world. Often “projection” is used as a term of self-deception. When I project emotions onto another it is because I am feeling them not because the other person necessarily is. However, I would be just as wrong to assume by projecting emotion onto another mind is entirely deceptive. While we can be deceived by projecting meaning where there is none, we can also err by not projecting any mind onto a human body, thereby dehumanizing them. We do not say that by dehumanizing someone, we are not deceiving ourselves enough, though that would be the logic of equating projection with deception. Projection is required to recognize a living human body as a person.

However, I do not think that projection should stop at the materially contained. As we mature our meaning rises up to more abstract levels. For example, let’s say that meaning for a young man is derived from the approval of his father. That began directly from his projection of a certain mind on the person of his father, and that meaning would only persist when his father was watching. When the son leaves his family, he then carries that meaning with him throughout his life as a desire to be approved by his teachers, his boss, other worldly authorities, and even a more abstract value system such as what leads to career development. The total effect is the perception of a mind without a spatially unified body. The mind that is perceived is dispersed among those things which are revealed as relevant in that meaning system. This is how the ancients perceived gods, as minds which contain certain value systems and have multiple dwellings (hypostases) in the material world.

Meaning, then, is the experiencing of an “other” which can be embodied in the relevant visible objects. By making the pursuit of wealth the primary source of meaning in one’s life, meaning is dispersed throughout all things related to the gaining and retaining of riches, including other people. For the man possessed by such a spirit of greed, all things become meaningful by the influence of mammon, and the man becomes a dwelling place for the god, like a slave who fully internalizes the will of his master.

The man enslaved to such a narrow meaning system is surely deceived. The question is in what way? Surely, we agree that such a narrow lens on the world will see things irrationally. He will be unable to predict or understand things which do not fit in a world ordered by greed (motherhood, for instance). But I would argue that the error is much deeper.

Consider a man possessed by lust. He projects onto the object of his lust a desirousness for him. But if the woman is truly desirous for him, that she is just as possessed by lust as he is, does that justify his lust? Is he right in his perception of the mind of the woman? According to some readings of truth, it is a match made in heaven. The projection aligns with the “reality” of the world. However, accurately perceiving minds is not an ability to read emotions or predict behavior or treat someone according to their motivational state. Seeing minds is the ability to perceive the ineffability and transcendence that a mind truly is. The man does not perceive the mind of the woman, he perceives only his desire for the woman, and considers himself justified when her actions seem to confirm it. The witness of minds, and of meaning is not like the scientist aligning his hypothesis to his observation, as an object among other objects. Though this will grant us some emotional health, recognition of meaning and minds in the world must stand on a deeper foundation.

“Beloved, do not believe every spirit, but test the spirits to see whether they are from God; for many false prophets have gone out into the world.” (1 John 4:1)

A New Cosmology

In the old cosmology, we’ve seen that since there is nothing beyond the meaninglessness of the physical world, any meaning perceived would merely be a reprieve from an otherwise meaningless reality. This is likened to the pagan perceptions of gods in this world which can be negotiated with and which promise reprieve from suffering but are ultimately detached from a convincing source of meaning. Idolatry is then the attempt to capture a god (or meaning) into an object in hope that one will be able to have control over one’s fulfillment in the material world. By acting as if meaning is only a product emerging from material, and will eventually return to the meaningful, we desperately seek to gain control of our own satisfaction by grasping at and controlling meaningful things. We become idolators when our hope for full satisfaction is in the finite things of the world, as if finite objects could satisfy an endless craving for meaning. There is no other option when the world is closed to a truly meaningful reality.

Just as perceiving another person as a mere object (even a complex object, like a “rational animal”) without the ineffable subjectivity of a person is to misperceive his or her mind. It is likewise an error to perceive meaning as being something which ends in the material world. If some desire can be totally satisfied by the world, it is not meaningful, just as if a mind could be totally known as a material object, it would not be a mind. Real witnessing of a mind is an opening up towards a mystery. Real meaningful pursuit does not promise satisfaction in this life, but as it is pursued, it opens up more and more toward the infinite source of meaning. Meaning does not beget satiation, meaning begets more meaning. When we seek the end of meaning to be in the world, we spiral towards enslavement to the world.

We’ve talked about two options: nihilism which denies the reality of all meaning and idolatry which treats meaning as being fulfillable in the finite world and inevitably enslaves us by promising what it cannot give. The third option, which I wholeheartedly suggest is to see meaning not as being satiated by consummation of the world, but by our directing ourselves toward the source of meaning (“from God,” as St. John says). Meaningful living is truly to witness the world as if a transcendent Other is what is granting it its meaning. In a proper disposition, as we discover more about a person, the greater the depth and mystery of their mind becomes. Likewise, the pursuit of a meaningful life is akin to a recognition of the “mind” at the source of all meaning. On this path we become less “satisfied” by worldly things and more “satisfied” by coming into greater relationship with the ultimate, transcendent source of meaning. We will no longer see the things of the world as potential solutions to our yearnings, but as earthly signs of heavenly order which can point us towards knowing the transcendent mind.

Since the good of an object gets its meaning from a higher place, and by our taking of the meaning for our own satisfaction we reject its natural goodness so that we may have it as our own goodness. It reminds me of the Buddhist saying: “do not confuse the finger pointing at the moon with the moon.” What meaning is found here on earth does not by itself bring satisfaction, but fills our life with purpose by pointing to that mysterious, untouchable thing in the heavens that illuminates the dark night. By the finite object, we come to see the infinite, invisible, eternal God, the mind at the font of all meaning.

Conclusion

Let us recap. To be a materialist is not an outcome of the greatness of science. Rather, it is the denial of something unrelated to science: a spiritual reality where minds exist as ineffable sources of meaning. When we see the world as stuff, consciousness is a problem. However, when we see reality as having both material and ineffable, transcendent minds in it, consciousness is then recognized as a mystery. A mystery which cannot be understood totally except in the revelation of meaning in the world, that consciousness is beyond total human comprehension, and the real satisfaction of meaning is found, not by consummation with objects, but by coming into relationships with that mystery. The only way of coming to realize that mystery is by a sort of faith that the meaning one has received comes from a true source of meaning.

We began with taking the materialist position seriously and seeing how it could accommodate consciousness. In my attempt, we could not justify the view either in practice or in theory. In practice, one descends towards an impossible to live with nihilism (and eventual enslavement to tyrannical powers). And in theory, the materialist thinks the world is only composed of things, while consciousness is proof that there are “things” which are not things, that are completely unobservable, which cannot be proven by any evidence the materialist would find compelling according to his own framework.

The figure of Sisyphus is the hero of the existential and materialist ideology. He is the figure who while knowing all things are meaningless, still labors, and as Albert Camus implored, we should imagine Sisyphus to be smiling in his fruitless labor. “The struggle itself towards the heights is enough to fill a man’s heart. One must imagine Sisyphus happy.” However, I think this interpretation of Sisyphus sneaks the true hill in, because instead of the hill being whatever labors you do in life, the hill is now how do you learn to smile while suffering in pursuit of the good.

That hill, in my view, is the real one to ascend. On it, though there can certainly be setbacks, the boulder does not roll back down the other side except by our own will. This hill represents coming closer in relationship to the source of all meaning. This would not be a being (or object) itself, but Being itself, an ever-growing relationship with the infinitely transcendent mind, who like all other minds, requires faith to encounter it and receive its riches. The psalmist thinks of the Messiah, not Sisyphus when he asks “who shall ascend the hill of the Lord?”

This article is the first of three which describe the Triune God of Christianity as it solves the problems of today’s worldviews, which are mere repetitions of old heresies. The ineffable source of meaning is most identified with the Father, as the Divine source of spiritual beings. However, God is not only Father, but Son and Spirit as well. To take one without the other two runs the threat of other mistakes we can make in how we understand what is at the foundation of the world. And these we will be able to always keep in mind as we explore the nature of the human mind.