A previous article was concerned with how the brain shifts to a broadened attention when not much is going on in our environment. We can also look at how the mind functions when things do get exciting. The attention focuses, and we quickly react, as opposed to the non-reactiveness of a calm environment. In some way, the excited mind seems to be in be the opposite state, but in a way, it transcends the way we normally think of consciousness.

William James describes aspects of these two extremes. In low-salience environments, we can experience extreme dispersed attention as James describes:

“Most of us probably fall several times a day into a fit somewhat like this: The eyes are fixed on vacancy, the sounds of the world melt into confused unity, the attention is dispersed so that the whole body is felt, as it were, at once, and the foreground of consciousness is filled, if by anything, by a sort of solemn sense of surrender to the empty passing of time.”

And the opposite he describes as moments “in which absorption in the interest of the moment is so complete that grave bodily injuries may be unfelt.” You may have experienced something similar while playing a sport or instrument or an activity that allows one to get into a state of flow. These activities promote the state of consciousness where much of the background seems to melt away. and the task becomes only you and the relevant objects in front of you.

Both of these extremes seem to allow for an altered state of consciousness. But how does being in some intermediate between these give us consciousness as we know it? We constantly fluctuate between, but seldom reach, these two extremes. To better understand our general states of consciousness, we need to understand these extremes and how we go in and out of them. The focus of this article is on the focused or constricted attention in highly exciting situations. The broadened attention of calm environments I have written about elsewhere.

Initial Reactions

With constricted attention, in its extreme, we hardly have a conscious mind. In fact, we do, but it is unreflective in its dealings with the shocking, high-salience events we must be wired to react to. If anyone has had a sudden traumatic experience or an intense thrill, they may rarely be able to describe what was going on in their head. They had been in a purely reactive states, where consciousness was practically unnecessary. When the athlete is asked what he thinks about when competing, usually the honest answer is nothing at all.

Why this happens is likely because, with highly reactive things, there is little time for a thought. We make time, however, through our quick reactions. Highly-salient or emotional things elicit in us a reaction that buys us time to deliberate on the best way of going about it. We get tunnel vision because any more information is, at best, unnecessary—and at worst, distracting. This mechanism, as we know from experience, can be embarrassing as we can flinch at things before we know what they are, or react angrily to something which deserves no reaction. But overall, it is beneficial to be able to react without conscious thought.

Joseph LeDoux describes the reactive portion as the “danger detector.” This is the part of the brain that can react to very simple threats which have pretty instinctual responses. It does not necessarily have to be a “danger,” however, danger is something we usually must react to the quickest. But he will also describe our “fact checker.” The reflection on things can give us more information once we have reacted and are out of danger. If we jump when we see a snake, we do it automatically with extremely narrowed, unreflective attention. When we are safely away and have time to deliberate, we take in a broader amount of information, and we find that the snake was only a stick.

Attention and Reassessment

However, we know it is not accurate to call such reactions a narrowed attention. Reaction is a blurry wave of action, and attention seems to be a calmer, conscious focus and awareness. The reaction did not require any higher awareness, but it does orient our attention to where it needs to be. This is where attention does come into play.

It feels like narrowed attention because when in a reactionary mood—and, like focus, we mostly react to one thing at a time. But attention, when held long enough, supplies extra information about the object of attention. If we are able to lay our attention on something without reaction, our minds can gather the details of that thing, and understand the overall situation to inform better actions. In an intense situation attention rarely is able to broaden; it remains continuously orienting to the highly-salient things.

However, it does broaden some, the whole situation is not coped with purely by unconscious reactions. Attention comes in the tiny moments of reassessment of the very deeply wired ways we react to the environment. The “danger detector” has a broad umbrella of things for which it would rather be safe than sorry in reacting to. But the attention can quickly supply some more of the accuracy to this reaction.

Combinatorial Ability of Attention

How does attention help us reassess the situation we momentarily reacted to?

Attention has the ability to combine qualities that are not yet cemented in the perceptual or conceptual level of awareness. We have many habits of reaction, which do not need attention to perform. Attention can combine bits of information that are not yet strongly associated enough to cause totally automatic reactions. We can react to the general thing, but attention to its uniqueness and its context is required to supply sufficient information.

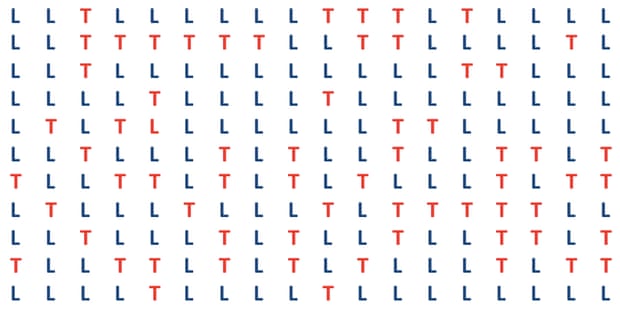

This effect of attention in relation to the reactionary moments is strangely demonstrated in much less exciting circumstances: a search test. In screen of red Ts, it is very easy to pick out the blue one. It is a simple perception and an automatic reaction. But when you hide a red L in a field with more complex distractions, it no longer “pops out,” it requires attention, and the task takes much longer because instead of reacting, we must combine more subtle qualities of the object to find the L. The purpose of attention is to broaden the information that contributes to the understanding of the attended object.

This is an example picture from an article in The Guardian.

Over-Narrowing of Attention

In high-salient situations, which do not let attention broaden, cause some obvious problems, especially if we carry that highly agitated attitude with us even in calm situations.

I-witness accounts of crimes or accidents show investigators the narrowness of attention when it comes to intense situations. Accounts of a crime can be tremendously flawed, because in a high-intensity situation, we react, and attention if it can be salvaged goes only to the most relevant information. And that is all we remember. We cannot see if the criminal had glasses or what clothes he or she was wearing. We are in fight or flight mode and hardly exit it to look at the broader picture to gather information on helping potential investigators. This is a difficult skill to learn, where only emergency first-responders and military personnel are trained in it. One needs to learn non-reactivity to these intense situations so they can continue surveying the situation and react intelligently according to their protocol. It is a truly amazing feat of overriding what is so hardwired in our biology.

This narrow attention not always a bad thing. Of course, it may get us out of a dangerous situation alive, but we also can have amazing and productive experiences by harnessing it intentionally.

Flow and Focus

Flow is a term used to describe the moments in which we forget ourselves in a task at hand, when we are “in the zone.” What is occurring to attention is a fluctuation between total instinctual reaction and more reflective moments when we do not come too far out of that feeling.

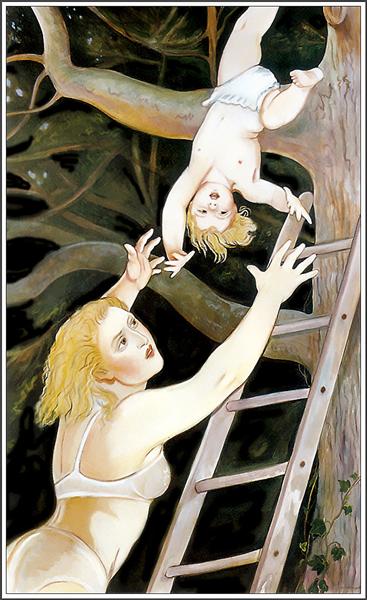

We often do not lose ourselves completely. Especially in starting out, it is very easy to fall out of that flow feeling if our attention is a little too broad and wandering. But in it, we move from excited reaction, that is often a practiced skill, to assessments of the slightly broader situation. A skilled rock climber may react with grace in the moment, but she has to widen her scope of attention to look ahead. This may only be briefly. I think, if she were to broaden here attention to far less present things, that may cause a panic for being in such a dangerous situation. The climber knows that that attention cannot leave the task, because of its danger. Other tasks can elicit a flow state, but do not have that benefit (or actually the threat that rock climbing has).

One of the requirements for flow is skill. Of course, by this I mean technical coordination, but I also mean a skill of using attention. For someone to be skilled at something requires practice, in a reflective, self-aware state. The drills we do to practice our talents are done, often, with self-awareness to ensure the proper technique is being used. When one is well-practiced, one will be able to do these actions without reflection, and thus without taking them out of a flow state. Thus attention management is a part of any skill we can acquire too. An expert-climber will know what variables she will encounter on a climb, and she will know exactly how to find them, and how to react to them. With these skills and a task difficult enough to hold one’s attention, a flow state is practically guaranteed.

Focus, is slightly different than flow. What we often mean when we say “focus,” is quite similar to flow; however, I would argue that it is more difficult to prolong than flow. If we are trying to creatively focus, such as in writing, thinking, problem solving, or creating any artistic work, we cannot always rely on the narrow mindedness of a simple task to grant us success. We must broaden our attention out of what is seen in the flow states, but also quickly be able to re-engage with the exciting task ahead.

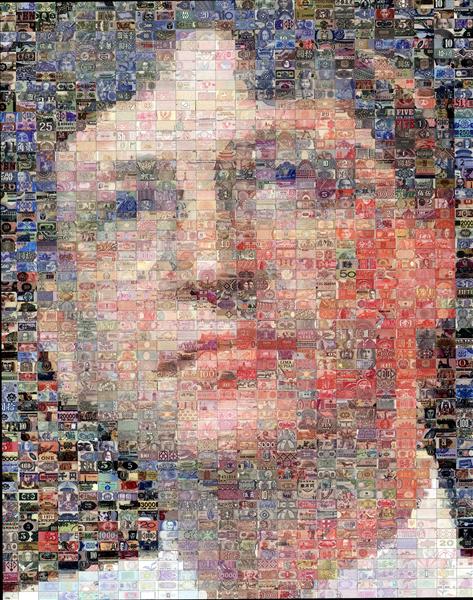

Many artist and thinkers will describe their best states as likened to flow states, and we should trust them, for much of the activity of creating is in the work which, if practiced can be exciting and engrossing. But for true creative work, one must be able to broaden one’s scope of attention to many other things, to consider other options, or entertain other points of view, listen to the unconscious. What happens with attention, is not that it leaves the creative work completely, but it remains on it, with a broader view. It looks at the work as if it were in a complex web of other works and other experiences. This is where we connect our work with a broader meaning in life, to ensure that part of us is left in this work, that it is not simply a display of talent, but a display of the soul and its experiences. Creative work may need to do this occasionally, but the creator must still be able to re-access a flow state to get the bulk of the actual work done.

This is something that, the father of “flow,” Mihaly Csikszentmihalyi, writes in his book Creativity.

“What is so difficult about this process is that one must keep the mind focused on two contradictory goals: not to miss the message whispered by the unconscious and at the same time force it into a suitable form. The first requires openness, the second critical judgement. If these two processes are not kept in a constantly shifting balance, the flow of writing dries up.”

The first that Csikszentmihalyi mentions is likened to the broad attention which takes in information from many different, quiet sources, and the second is likened to a flow state of the technical work, that if done with skill is highly enjoyable. Imagine the excitement of a mathematician working on an equation that his soul has told him to work out.