A simple organism has simple instincts. A stimulating situation is coded into its biology to cause a rather predictable response which is necessary for its odds of survival. Instinct, as a psychological topic, originates in the realm of physical and chemical responses, William James introduces behavior with the example of iron filings unintelligently moving towards a magnet; they do not adapt to the situation if a barrier comes between them and the magnet, the simply press to the surface of the barrier.

Similarly, in a basic living organism, bacteria fleeing a toxin can only change its direction randomly and go forward, until it senses that the toxin is less concentrated, and it continues in that direction. In this way, a very simple mechanism can reach a seemingly intelligent goal without any conscious awareness of what that goal is. An instinct is a potentially beneficial action where the organism has no awareness to the purpose or goal of the action but is compelled to do it anyways.

“Instinct is usually defined as the faculty of acting in such a way as to produce certain ends, without foresight of the ends, and without previous education in the performance.”

William James

In the complex environment having these rudimentary instincts could be dangerous. Our survival should not depend on instinct alone; we need to adapt. Our needs and environment are more complex than the needs for bacteria colony to survive and reproduce. We cannot simply run in random directions, like the bacterium, until we sense that we escape a danger—despite the entertaining notion of that being actualized in cartoon. We need, and have, more tools to use and instincts to guide us.

Fine Tuning Instinct as Habit

Animals that learn from experience and adapt their behaviors all have instincts. But instead of singular instincts, those of more complex animals’ conflict and keep each other in check. The result is adaptive behaviors where these instincts may still reside somewhere in the psychology of the animal, but if they are not used they can atrophy like the muscles of a casted arm. On the same token, instincts which are used can strengthen and become dominant. There are two elements to this adaption of instincts.

Part of this learning is in the specificity and generality of the stimulus and response, which is a matter of one’s ability to differentiate and group stimuli and intelligently respond to them as such.

The other part of learning that is in the strength of the impulse, which is trained by experience and practice. The instinctual impulse driven by a stimulus is like the current of water which, in seeking the lowest ground, carves out a deep and sure river where the more water travels easily down it. The more an instinct is used with success, the stronger its impulse will be. When we think of forming habits, we are talking about exercising our instincts. Habits are basically matured instincts—the patterns of behavior whose plaster has set. Instinct came from a biological origin and habits from the adaptation of that biology with the environment with practice and experience.

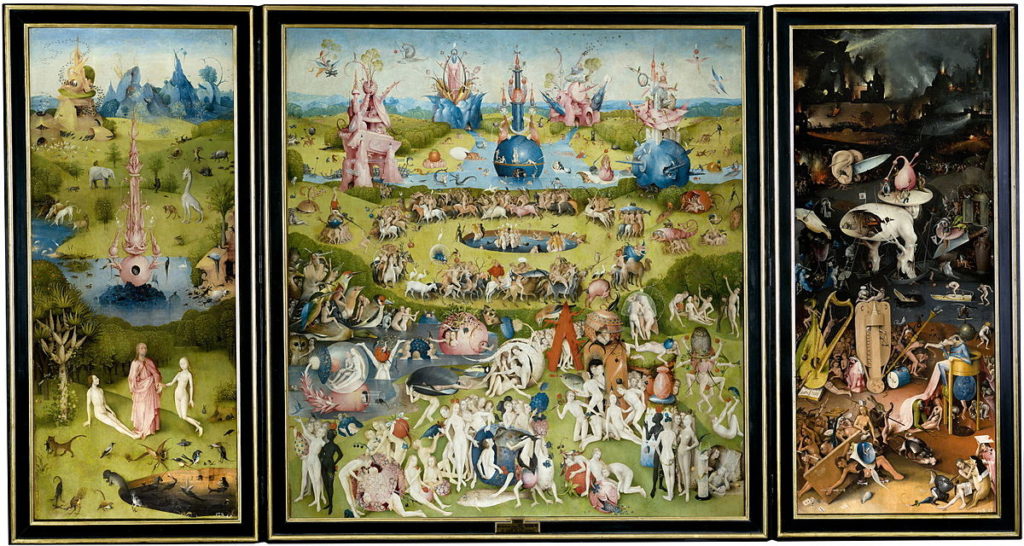

Being Without Instincts Is to Be with Too Many Instincts

We can think about our ability to adapt using a diversity of responses not as evidence of us being instinctless, but rather as us having many, many instincts, including those that conflict with each other. At this point we should be careful when we call something animalistic because it appears to be an instinct and calling something “higher” because it resists as so-called instinct; for the higher purpose is merely another instinct, which may have better social outcomes in some circles, so we give it a positive title.

“The animal that exhibits [conflicting instincts] loses the ‘instinctive’ demeanor and appears to lead a life of hesitation and choice, an intellectual life; not, however, because he has no instincts—rather because he has so many that they block each other’s path.” – James

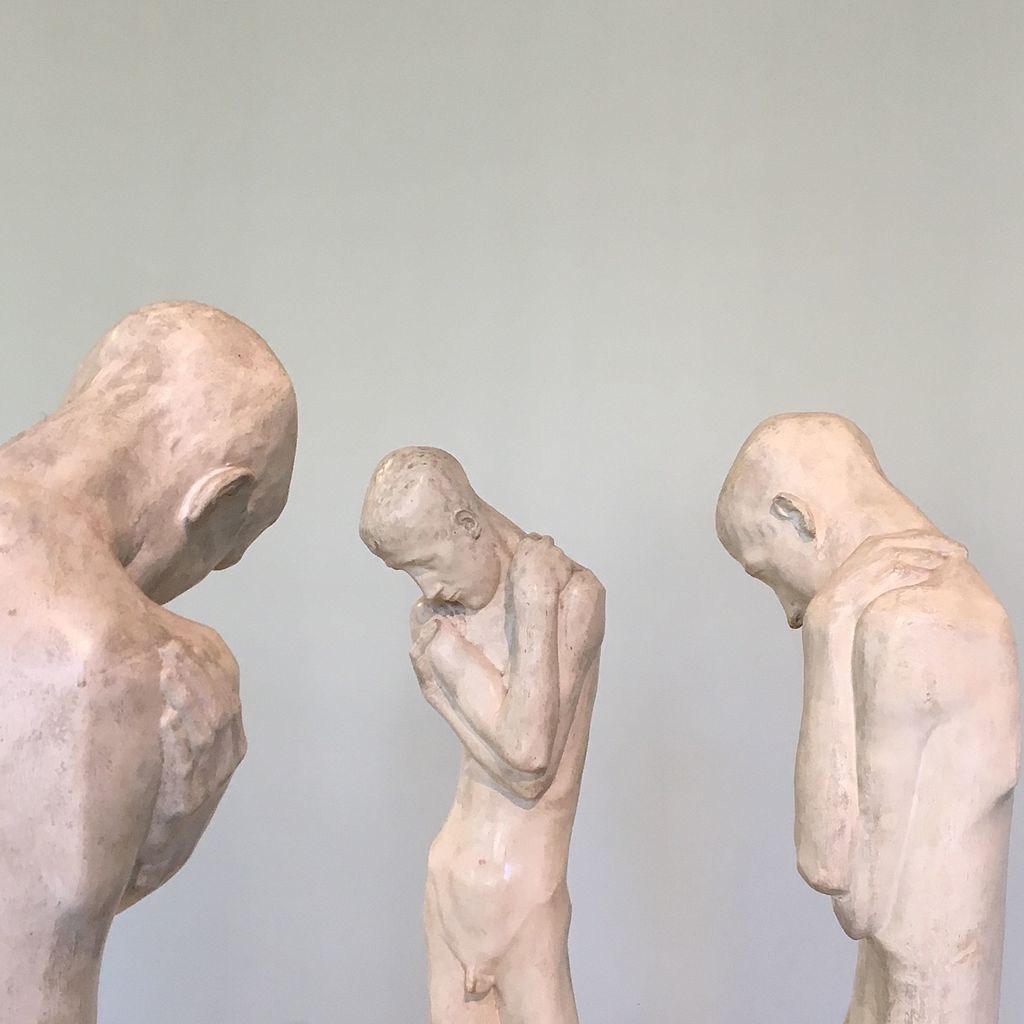

Deliberation and Emotion

If two instincts conflict they cannot both result in action, because we are for the most part limited to only one action at a time; you cannot both stand your ground and flee, even though both impulses are caused by the same frightening event. Rather than frantically going back and forth between two strong desires, like a child who is only allowed one toy to bring on the car ride, the instincts manifest as emotion, contemplation, and hesitation.

When the instinct to socialize conflicts with the instinct to protect oneself in new environments, we do not switch from one extreme impulse of socializing to shutting oneself away all in one night. Instead we feel, in the background of our consciousness, the emotions which force our attention back on the appeal of one option and the consequences of that action.

“Every object that excites an instinct excites an emotion as well. The only distinction one may draw is that the reaction called emotional terminates in the subject’s own body, whilst the reaction called instinctive is apt to go farther and enter into practical relations with the exciting object.”

William James

The Intelligence of Emotion

Emotion is instinct which needs an added degree of intelligence to figure out what the appropriate action is. To feel emotion is to have two or more instincts contradicting, which their discharge is redirected into an attitude toward the situation, attention to the important parts of the situation, all the things that we know as characteristics of emotion which can help one think and deliberate on the appropriate action. It is the instincts which meet no resistance which are emotionless and often cause regrettable reactive action, which we later blame emotions as the cause of. Emotion gives us the proper ground for contemplative action, not an instinctual reaction.

This is noticed in how we react to frightening objects. A snake hiding in the garden will create an instinctual jumping-back reaction, but the moments of fear happen when one need to deliberate the next action, because the quick reaction would not benefit us if it goes unresisted. If there is no impulse against running away, then we will run away to the extent that the instinct needs us to. However, there is almost always something to conflict. Like a social instinct to appear brave in front of another or get on with gardening. This is when we feel fear that doesn’t cause us to act right away, but to deliberate on that fear and consider one’s other goals.

Instinct gives us the quick generalized reaction, and emotion, which guides attention gives us motivation to fact-check, rethink, and consider other goals. Emotion tells us how to go on from that initial instinct or habit.

In this sense, emotion is our motivation to intelligence. And what we call intelligence today is usually an instinct or habit that people agree upon as socially thoughtful with long-term planning. Emotion, in this sense, tells us how we need to use our instincts, it allows us to correct our habits. But instincts bias emotion by affecting the body, which we feel, in a way that it would affect it in order to act, but simultaneously giving us the bodily character of emotions that we easily recognize.

What we call emotional intelligence is really our habit to focus on goals that benefit us in the long-term. We are intelligent when we pass up the junk food because there is another goal we have emotion towards and we have formed a habit to react it. We are intelligent when we define a loved one’s anger as a need for love, rather than a personal attack, a redefining of the reactive stimulus caused my empathetic emotions—from empathetic instincts. Emotional intelligence is to create behavior patterns which minimize conflicting results in the near and distant future. We must navigate a narrow course of not inciting undesirable effect of our emotions for our long-term or short-term wellbeing. This requires contemplation which happens, not in spite of emotions, but because of them.

Flow of Intelligent Instinct

When we think of intelligence we normally think of something entirely good. But in this sort of intelligent deliberation between impulses there is a downside of inaction. Caught in between two equally appealing instincts we get stuck feeling an emotion that is unresolvable. We become hesitant and we never develop a habit of action, but merely a resigned emotional state that one will typically seek to resolve by distraction. We all know what it is like to eat our comfort foods when faced with a problem which requires intense deliberation and seems unresolvable.

For this, William James understood the true downfall of deliberation and the inability to create habits:

“There is no more miserable human being than one in whom nothing is habitual but indecision, and for whom the lighting of every cigar, the drinking of every cup, the time of rising and going to bed every day, and the beginning of every bit of work, are subjects of express volitional deliberation.”

William James

Being in a flow state is to be without the need for deliberation. One knows what is best and one does it. In this way, flow transcends emotional states by being something that one achieves enjoyment without deliberation. It is a bliss of existence where impulses which we are accustomed to build up, are released as a habit, like in painting or writing or exercise.

And a word of warning from the other extreme is that, without reflection, emotion, and deliberation, we could end up strengthening the instincts which put us in regrettable positions in life, which take a lot of time to get out. In Flow, Mihaly Csikszentmihalyi says that without stopping to reflect one “may sail through several years successfully and without hesitation,” and “postponed alternatives may reappear again as intolerable doubts and regrets.” We must know how to adapt and commit to those adaptations.

With a new angle on what emotions are for, and what the bliss of habits are, we might get a step closer to creating lives which are both enjoyable and deliberate.