The objective of early childhood is to provide the holding environment that allows the child to assume that things follow from his or her intention. This is an early understanding of causation between the mind and the world. Between which one has actions and impulses. Whether the outcome good or bad, it was believed to be willed. This means that the child understands itself to have bad intentions as well as good.

This structure of believe, has its problems, clearly. As adults we understand that this is a delusion, yet it is a delusion that we must unlearn. As the child begins to see the workings of intentions that differ from its own, a new adventure opens up.

Here is the story of how the genesis of a restriction creates a new adventure for the child and what that means for us now. How do we understand the “shalt nots” in our life?

The World Conforms to Intention and When It Doesn’t

In the ages anticipating toddlerhood, a young child is learning that the world reflects its own intention, typically with the mediation of the parents, as a space where all known things seem to correspond according to wishes. This is a basic assumption if the child has been raised with responsive parents. The infant has learned to bring to the world its own intention and that is how it maintains the blissful relationship and communication with its mother. It seems that merely wanting, and communicating that with the world, will often achieve its goal.

This stage is full of fantasy play in which the world has become endowed with objects to be understood and manipulated by the child. Thought and action have not become distinguished entirely. Intention is something the infant must communicate to make things happen, but it is not clear that the child knows how it is doing that. It may learn those communicative behaviors through the basic forms of learning such as operant conditioning. It may be a sort of operant conditioning effect where reward encourages more of that behavior. What is conscious is the intention or impulse, but the means have not been brought to attention yet.

The world that conforms to one’s thoughts is not necessarily an excellent world. There may be plenty of reward with it, but there is also punishment. Yet the punishments are not exceptions to one’s will; rather the punishments are the expression of the “bad me” or the shadow. To Harry Stack Sullivan, this is the preliminary stage of the “self-system.”

“Sullivan speculated, different areas of the child’s experience take on different valences. The activities of the child that tend to generate approval . . . are organized together under a general positive valence (“good me”). The activities of the child that tend to generate anxiety . . . are organized together under a generally negative valence (“bad me”).” Freud and Beyond

Anything that happens to the child in the presence of the known, the parental holding environment, is assumed to reflect the intentions of the child. The child gains it moral code based on the immediate outcomes of its intentions and needs. This is reflected in Lawrence Kohlberg’s stages of moral development.

According to Sullivan’s theory, it is after this does the child begin to learn what is “not me.” It is when the child comes across high anxiety situations that means that something was not intended, something “not me.” The reaction is that anxiety creating thing, is something to be made psychologically out of bounds. I would also argue that there are other forms of putting things off limits to the child. There are softer ways to create a “not me.” Those are prohibitions where parents do not allow impulses to be followed through. At this point, the first rule is made, a new entity is realized.

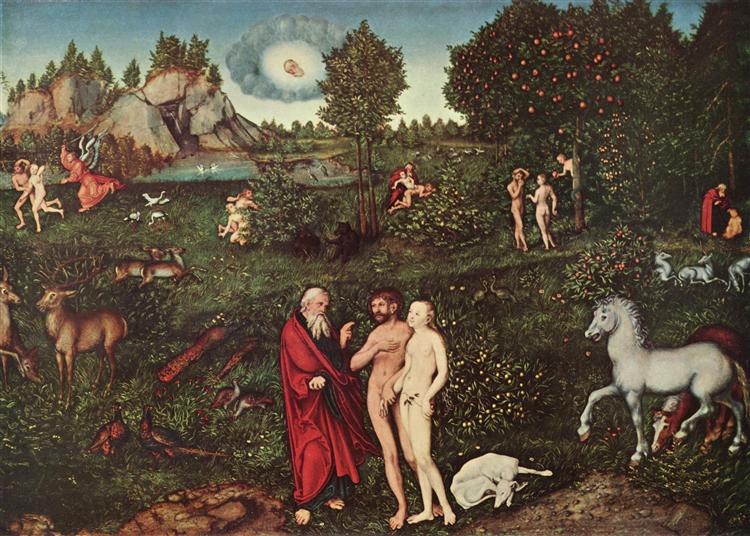

What Happens in Eden: The One Rule that Is Broken

As we look into what constitutes the first rules for a child, we can look towards the earliest rule that we have recorded in literature. This is the rule that God demanded of Adam and Eve to not eat the fruit from the Tree of the Knowledge of Good and Evil. This story recalls many similarities in the events I am trying to describe in childhood.

The Garden of Eden suggests a place of perfection, yet we know that the preceding stage was not perfect, there was still punishments. To this, I say that the perfection of the Garden is a nostalgic representation of this stage as a child looks back at before the breaking of the rule, one was more whole, but naked and blind. After the fruit is eaten, things get more complex before they get better.

When a child is operating in the “Eden” stage, she will have her intentions reflected in the world. But there will be moments when her actions are so severe to the parents that they come forth with great anxiety to snatch the child up from whatever danger she put herself in. This patterns as neither punishment nor reward, and not intention of the child. Something outside “me” happened. A higher being made something forbidden.

The forbidden thing is not understood by Adam and Eve, it is not a concept familiar to their previous way of thinking, nor for the child. To restrict a child means to prevent its way of understanding how to act. The child must now confront obedience or temptation, without full understanding what will happen because of that choice; the threat, in general terms, is abandonment.

However, the rule will inevitably be broken. Previously our moral system relied on the immediate results of actions (communications of intentions), but we are left with only curiosity at the outcome that is prevented. Being provided a rule yields temptation, for the child learns its moral system by trying things, not trusting an authority. That explains the immediate curiosity of Adam and Eve and the inevitability of their eating of the fruit.

“We do not have laws because we have desires: we have desires because we have laws, they want us to believe.”

Adam Philips in Unforbidden Pleasures

Temptation as a Call to Adventure

This is a rule of a higher order, made by the creator of the walled garden, the parental holding environment. If we take the story of Adam and Eve as something destined to occur, we realize that, from the current reality, the first human could not have obeyed the rule, just as the first rules given to a child will not be understood. We are fully aware in our lives that the apparent restriction to the impulse that ensures the strengthening of the impulse, or an obedience the does not understand what could happen.

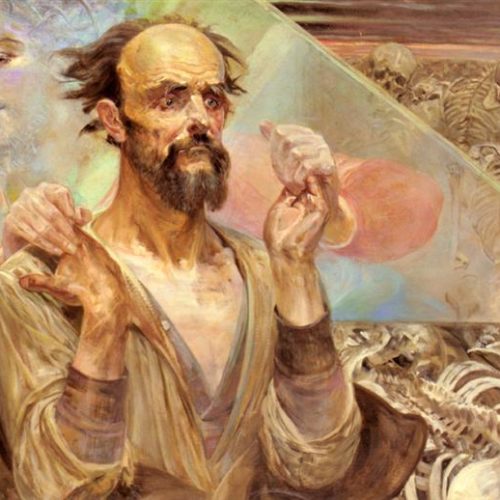

The image of the one who makes the conditions which allow you to stay in the Garden of Eden is an image of something “other.” It has a higher power, like the image of God or of the parental archetypes. This is the beginning of the idea of conscience. It is how the child will deal with this that creates how the conscience or Freudian superego is developed in the child. At first it is imposed from without, but then will be internalized in the process of heeding its call. To integrate the conscience, one must break its rules.

Adam Phillips writes about the paradoxes in forbidden impulses in Unforbidden Pleasures. Here he sites Donald Winnicott’s belief that what is to be feared in development is not a child’s unruliness, but “that the infant shall give up spontaneity in favour of compliance with the needs of those who are caring for the infant” To Winnicott, the infant’s quick compliance with the needs of others is a loss of hope.

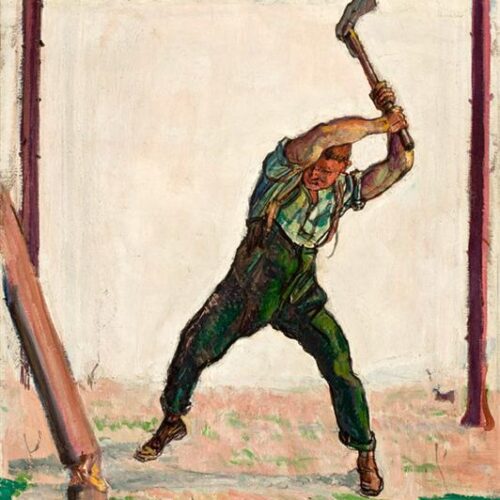

I do not want to suggest that Adam and Eve ought to have broken the One Rule. I say only that they did what naïve, and hopeful child does: become revolutionaries to boundaries that do not make sense. This story is the call to adventure that leads to the rest of the Bible. When a child disrupts their Eden, they are called to repair it, and usually that is a long and trying adventure.

Our Adult Authorities

“You only find out what your obedience entails, what it has been costing you, when you are disobedient. It is not that rules are made to be broken, but that you find out what the rules are made of in the breaking of them, as well as what you are made of.”

Adam Phillips in Unforbidden Pleasures

Before going into what this leads to in the early stages, I want to describe how we can recognize the integration of the call as we are older.

Those “shall nots” of our childhood are deeply buried. They can be the rules that you never tested or intentions that caused undue anxiety. But the key here is recognizing them in yourself. The “not me” that is the opposite of the “obedient me” is the shadow whom we wish to abandon. It is in those people who you feel are particularly lawless, that you may find what you have forbidden in yourself, a temptation of an impulse not perceived for many years. That is not to say that one ought to indulge, but that one cannot know if that law is just without having the ability to break it.

This brings to mind the image of teenage rebels. Rebellion from these rules may look like rebelliousness in the culture, but not all rebellion is an honest attempt to discover what is behind one’s unconscious superego. The aim of this rebellious feeling is not that rules are an evil, but that morality is not reliant on mere obedient good intentions. We have to get beyond the threat of abandonment to be adventure-bound where much more happens in our relationships to rules, God, parents, and morality.