In this media-based era, attention has been something that we have struggled to control. With all the powerful and provocative imagery of overly convenient media and entertainment, it is no wonder we are becoming less able to harness attention for projects that are personally important. During this time of an attention-based economy, we must re-establish often the importance of attention on our lives, and in the case of this article, on how we fundamentally perceive the world. Let this be a light push to start thinking about the severity of outcomes of our highly distracted lives.

We are all aware of attentions role in staying focused on work and school, in getting things done. But attention has played a much more essential role in our existence. Attention is responsible for all of our learning, down to the sensory perceptions of the world.

If you have ever read a page of a book, or rather, scanned it with a wandering mind, you know that when you ask yourself “what did I just read?” you struggle to remember. You probably perceived all the words, but your attention was not on the ideas which they provoked, thus you could not connect the ideas from the book to your own ideas. When attention cannot link one idea to another, it cannot learn anything new. (It may seem like subliminal messaging is an exception, but that is a topic for a future article.) We simply need some measure of attention to learn new things, to pair ideas and see their relationship. Let’s look further into what happens with this learning and how it results in our representations of the world.

Making Life Easier

With incoming stimuli bombarding our senses, we cannot hope to get a complete picture of all of it. Instead our attention can be focused on essentially one thing at a time, but get a lot of information out of that thing. We build up a web of ideas and representations which guide where our attention needs to go. But originally, it was attention that was doing the learning.

By focusing attention between two separate things, one can discover the relationships between these things, and begin to see the things and their relationships as one fluid object or idea, obviating our need to pay attention to the two things separately. We can then learn to see a whole, which contains the nuances of the parts that make it up.

After this learning process the parts are sometimes forgotten if they never require any new attention. In his Principles of Psychology Vol. 1, William James gives us the example of a pianist who is unable to play from the middle of a melody but must start from the beginning. This is because he sees the melody as a whole, and forgot the minute perceptions of its center. We are not necessarily blind to the parts after learning, but we no longer require to attend to them to see a greater whole which we can interact with. And this makes our life so much easier.

We also see how this attention is so related to movements and interactions with objects. Often our attention-learning groups perceptions into ideas which represent the level of the object we interact with most. It is not the threads of a linen that we must attend to on a cold night, but rather the whole covering. In this way we see attention and perceptual learning can be governed by motivations and emotions and not simply some “external reality” which we are all guaranteed to share.

Importance and Development

Although we still learn by this method, its effects are greatly reduced as we get older. Much of the perceptual learning that we do by attention has been solidified early in life. Even by preschool age, we are so far along in learning by having once payed attention to the very basic things that made up the original “buzzing confusion” but now we now see as unimportant. If we learn to pay most of our attention to what is variable and important and ignore what is consistent and irrelevant, we can function pretty well in this world. For the consistent things, we can perceive and react without any conscious attention. In this way, a large part of us can we operate without needing consciousness so we can reserve it for making decisions and attending to more interesting things.

All this learning once came from attention, but it was an attention of following the most interesting thing, reacting and negotiating with parents, or just simply a curiosity of the new world. Our attention was basically reactionary and conditioned by our early environments. We would look on at a face and see the subtleties of its expressions. And we learn to pick up these things and get a larger sense of how the person is feeling, based on these subtle cues, and we know how to react to get desirable results. This was all governed by emotional values in objects which interested the baby enough to captivate his or her attention.

If some of these finely-tuned perceptions are not learned at an early age, they may present as social or emotional ways. Someone who cannot see the subtleties of facial expressions will not be able to have lasting social-emotional exchanges with people until they learn to see those details in the whole face. It is this dynamic that Greenspan and Shanker (in The First Idea) say is more relevant in how autism can start from biological causes but develop from social, emotional, and perceptual symptoms.

The nuanced perceptions we make and what we see as the important features of objects, is a result of attention and the emotional mechanisms go hand-in-hand with attention. Although much of our perceptions may be the same, because we all see the same physical world, we may see subtle, but ultimately consequential differences.

Changing: One Representation at a Time

Although a child’s mind is much more malleable than ours, we still always have a great opportunity to change the way that we see the world. The ability for us to change is unfortunately very difficult because we already have so many assumptions about what deserves our attention. Where a child learns things from the bottom up, we adults must break things apart and rebuild.

Attention can dissociate things, determine their individual importance, and reintegrate them into the whole idea or object. Seeing the subtle facial expressions or intonations on a level of detail that one has never seen before creates an object of a new essence. This is how we might be able to change the way we see the world by looking closer at it.

Complex motor skills are a good example to demonstrate how we might practically be able to change. If a first-time golfer watched a professional take a swing, he or she would be able to mimic the whole of what he or she saw. But if he or she paid very close attention to the fine movements, or better, was told what those find movements were, it would be possible to focus in on the smaller elements of a proper swing. This learning requires attention to the small adjustments of the body until one ingrains them into their natural swing. After that narrowly focused learning takes place, one can take a swing, without the need to focus on the small movements, but only full action. The motor changes will be subtle but will have effects on the whole, and we will no longer need to focus. The result is the feeling of a “natural” and precise motor skill.

For perceiving the world in an analogous way as a professional golfer can swing, we must be able to probe the world for the important nuances. There is so much in the world that we perceive that we are no aware are affecting our emotions and our perceived situations, so draw your attention around, and probe your assumptions. If we change the subtleties that our perceptions are accustomed to, we can change the whole, slightly, but meaningfully.

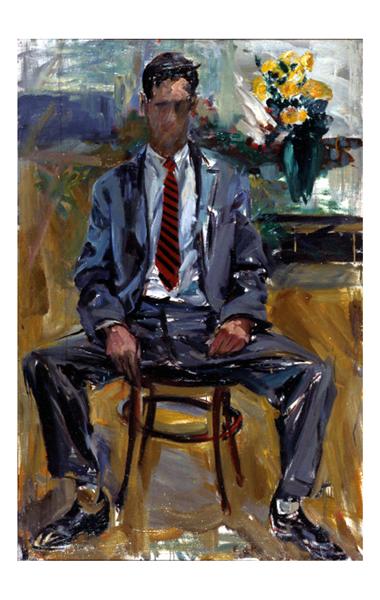

For me, the arts are a good tool for this. Like getting advice from a golf coach on how to fine-tune the wrist muscles for the perfect swing, an artist can alert us of a new way of perceiving the world. We can ask, what do the artists see that made them paint this? Why did the poet choose those words and what was her world like? Can we see a world like that?

But even better, we can create our own works. For those works to be good, they must come from a precise eye or ear or nose. When we write to describe a scenery, a good description will force us to see it in a way that we have never seen it before. Creative work should change the way we see the world.