In this set of three articles, I have argued away from the extremes of naïve materialism and naïve idealism. But I am not making an argument that these two realms are a false dichotomy. In fact, I think it is evident that these two opposites, meaning and matter, should be considered different in order that we understand their relationship. But while we separate these two worldviews, our objective is to understand their union, their oneness. That will be where our interest lies—where meaning meets matter.

The last articles offered critiques of the two world views and hinted at a new way of looking at both. Though I argued that it is impossible to wholly ignore either realm in favor of the other, I had not necessarily reconciled these two realms together. How are we to understand a world of material uniqueness coexisting in a world which is known primarily through its meaningful presentation? How do we navigate such a presently unnatural way of seeing?

The focus of this whole project is to shine a light on the subject of humanity through principles biology and psychology. When others take on this task, they always steer the reader towards a materialist perspective that humanity is the result of lifeless molecular accidents hidden by a false sense of meaningfulness. However, biology is the study of “life,” and as such, it is poised at the meeting of what is partial and what is whole, just as a cell is both working through its parts and as a whole. Though in studying biology we sometimes fall into the idea that the molecules are what is most real, we forget how the self-organized whole exerts just as much or more influence over the history of life. Likewise, understanding the molecular causes of life will not disprove the existence of any spiritual reality, a reality of meaning.

This article is meant to bring us closer to understand what we mean by “life” in a higher sense, the sense in which biological life is a prime visible example, but not the prototype. We ask not only what constitutes biological life, but what it means that the world comes “alive” for us, or how we feel when the world seems “lifeless.” It is not a coincidence that we use the same term for living beings as we do for these experiences.

Two Worldviews, the Two Mysteries

It will be important here to review the two realms which I sought to prove in the previous articles: the spiritual and the material. Matthieu Pageau defines these two succinctly at the start of his book Language of Creation. There, he expresses the questions of the spiritual worldview as “What does it mean? What truth does it embody?” The questions of the material worldview are “How does it work? What material is it made of?” These two perspectives are not incompatible, but they are asking very different things.

In arguing against materialism, I suggested that the undeniable subjectivity we all experience cannot be measured or known by seeing it from the outside as you would a material object. This fact is commonly expressed as the “problem of consciousness.” It is only through the experience within a mind that it can be proven to us. Whenever we are attempting to materially prove the existence of a mind, we end up falling short, because, though a mind may be tethered to material expression, its very nature is unseen. It is only in a relationship that we “prove” the existence of a mind—not by evidence, but by trust and experience of greater significance. The identification of another mind is taken as an unfractured whole, a meaningful experience, which gives us identity as an object in the view of another. Identity in this sense is what gives us meaning. Meaning of this kind always comes from without and is invisible to the eyes because it is derived from the perception of a mind, an authority, a source of meaning, which is immaterial. Knowledge in a spiritual sense is not gathering facts or even abstractions, but being in relationship, submitting to the meaning which is outside oneself. Therefore, meaning is mysterious in that it is invisibly contained in some Other, accessible only through relationship.

Then I argued against idealism, which I defined as being in denial of the role that material or earthly reality has in meaning. With a Platonic idealist view of meaning, we come to see all that does not readily conform to universal and parsimonious truths are rejections of meaning either making it an evil or by falsifying the whole pursuit of meaning. However, the material world should not be thought of as denying meaning, but as essential to the expression of meaning. The material is what has unique existence, which surprises us, resists the static meaning which we attempt to give it, and thereby reinvigorating the eternal with transformation and life. We can grasp at it and hold it and see it, but the tighter our grip (the more static we make our definitions) the more it slips away. Christians can understand this concept as pointing to the Word of God, who makes visible the invisible meaning and, in the person of Christ, surprises anyone who encounters him. Peter Kreeft writes his book Jesus Shock, looking into the fact that everyone’s expectations and categories were totally rearranged in their encounter with Jesus Christ. It is our encounter with the given, the unique, that surprises us, shakes us out of the prideful confidence that we are the source of all meaning. Like the spiritual realm, the earthly realm has its own mystery: it abides in a logic, yet is still unpredictable and unreachable.

My point in the last two articles is that true meaning depends on the connection between these two realms. Indeed, this is the sacramental worldview where the visible represents the invisible in a true and meaningful sense. The problem of consciousness is a modern question, not because of the progress we’ve made intellectually and scientifically but because of the loss of a sacramental worldview and the rise of dualism. And this is the answer to the lasting problem in philosophy of how mind and matter interact. The crux of the problem is not which of these two realms dominates, but how they are naturally integrated.

Epiphenomenalism and Inventing the Absurd

The field of philosophy called “philosophy of mind” is what deals heavily with the point at which mind and matter come into contact. One of the prevailing theories in it is epiphenomenalism, which gets its name from the medical term used for secondary symptom, a symptom that arises secondarily to the main disorder. Epiphenomenalism treats consciousness as a secondary symptom of physical phenomena, an outgrowth of physical material. It is generally a theory which takes the mind to have somehow been birthed by the complex object of the brain and body. The view often denotes that the mind, therefore, has no effect on matter. As a secondary symptom it is functionally irrelevant—an effect, not a cause.

What should be apparent to everyone who is vaguely aware of neuroscience is that mental states are contingent with physical states. When physical brain states are induced, the subject reports mental changes. We then infer that the physical world is what gives rise to the nonphysical world. This is reasonable to believe.

We can also see that when simpler parts are combined in complex ways, it gives rise to new phenomena. You need enough mass for a star to ignite; you need all the necessary parts of your phone to coordinate in order to make a call; hydrogen and oxygen atoms have nothing watery about them, but when they are ordered in a certain way, a watery property emerges. Likewise, we can infer that nervous tissue, once it reaches a certain level of complexity, will “ignite” and produce the previously non-existent phenomenon of consciousness.

Combining those two premises we get epiphenomenalism, which is the understanding of consciousness as an emergent phenomenon totally dependent on the states and complexity of matter. I think that is totally reasonable, especially given the material starting point. However, we can look at the consequences of such a project. Though epiphenomenalism seems to be a sophisticated view, it is dualism par excellence. That is because it starts with a dualist presumption essentially puts the two worlds in competition to see which is more real. Is consciousness more real than material? Or is reality composed of material with a garnish of consciousness?

Absurdity

The epiphenomenalist, accordingly, must say that consciousness and experience of meaning is a meaningless side effect of material reality. This is purported to be backed up by research that finds out that consciousness is not required for actions that were previously thought to require it. Julian Jaynes summarizes these studies very well in his book The Origin of Consciousness in the Breakdown of the Bicameral Mind. Psychologists in the era of behaviorism even went so far as denying any practical belief in the mind because it could not be measured, and therefore had no practical existence. As I mentioned in the first article, that is precisely what minds are, immeasurable and unobservable, but still somehow real. To the epiphenomenalist of this persuasion, we are helpless spectators, falsely imagining meaning in a world which is utterly indifferent.

Besides being a hopeless and absurd belief to hold, even according to a materialistic worldview, this is a stranger world than an explicitly religious belief. Apparently, indifferent, meaningless material seemed to, by a sort of accident, formed itself into meaning-making observers of itself, which, by the way, have no effect on physical reality. If you were going to posit a reality of a meaningless physical world, your theory is unlikely to include observers in that world. If materialism were a scientific hypothesis, it would have been immediately nullified by the fact that it would not predict a useless consciousness. Materialism predicts that material nature should have continued without the insertion of consciousness, a totally ontologically unique category into the world.

In order for the materialist starting position to recognize consciousness, it must posit some kind of function of consciousness that would have benefited the organism that evolved it.

Mind with a Function

“Each living creature must be looked at as a microcosm—a little universe, formed of a host of self propagating organisms, inconceivably minute and numerous as the stars in heaven”

– Charles Darwin

If minds do have a function, it can explain how they came about from a purely material world. It can explain how consciousness evolved to benefit our species. To an evolutionary biologist, minds would be presumed to have some function which benefits genetic propagation and survival. Therefore, yes, there is this anomalous “thing” we can call “consciousness,” but it can be explained by physical causes, and likewise all subjective and meaningful experiences can be subsumed by the physical.

However, every good evolutionary biologist should assume there to be an real environmental cause for every function and feature of an organism. Even vestigial organs or abilities should be assumed to have once had a function useful in evolutionary terms. Sometimes, what is thought to be useless, turns out to have purpose even when it takes centuries to figure out what it is (the large intestine and the appendix are two examples of this). Could consciousness be similar in that we do not yet know precisely its function? What reality is consciousness an adapted to?

If we look at a conscious being as a microcosm adapted by evolution to its environment, should we not presume that reality may contain something for consciousness to be adapted to? That reality, at its foundation, contains both observer and the observed. Then like the wings of a bird correspond to the reality of the skies, the mind of man corresponds to the spirituality of the cosmos, the potency of the world for meaning and relationship.

The evolutionary argument at the very least does not prove anything against meaning; it is just as easy to interpret the evolution of human minds as proof of a spiritual reality, as it is use it to buttress a materialist worldview. The rest of this article will describe the relationship of meaning and matter in a way that I find far more compelling than those which attempt to diminish one for the dominance of the other.

Body and Life: A Microcosm of Reality

We then ask where do we find examples where what is material and unique come into contact with what is whole and spiritual? The answer, I’d argue at minimum, is in the living creature, in life, and particularly in the body. Even the most skeptical of philosophers of mind will admit that the body has some role to play in the phenomenon of consciousness. But we can draw more out of this observation than just that. We can look at a biological body as a microcosm of the whole cosmos, just as I have quoted Darwin suggesting.

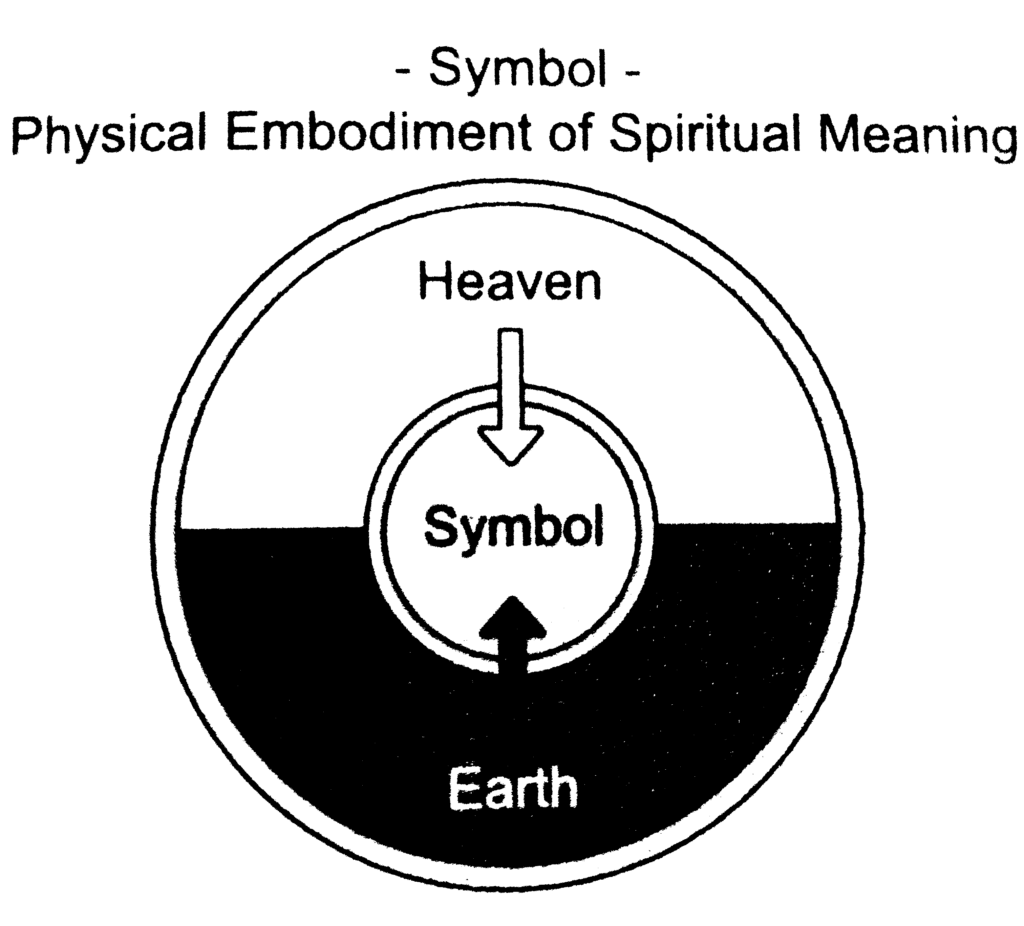

Therefore, we can think of the body as a visible sign or the invisible whole that it inhabits. In theory, we are able to know something about the environment an organism lives in based on its body; you could look closely at a creature and extrapolate its history and relationship in the outside world. In fact, that is what evolutionary biologists do to understand prehistoric environments. The “environment” is not something visible; though there is much visible about it and environment. It is a whole, diffuse situation. The environment is in the invisible relationality and principles of order, and that is what the body makes visible. In this sense, the body is a symbol of the niche in which it evolved. And within that symbol we see a microcosm of the universe, not just in its particulars, but in its more general sense.

When we look at a biological body, whether a cell or a human being, we see a dynamic interaction between the unique and changing parts and the ordering and constrained whole. In her excellent piece “Dynamics in Action: Intentional Behavior as a Complex System,” Alicia Juarrero puts it, “when parts interact to produce wholes, and the resulting distributed wholes in turn affects the behavior of their parts inter-level causality is at work.” Within the organism is an interaction where the parts give rise to and express the whole, and the whole constrains and orders the parts.

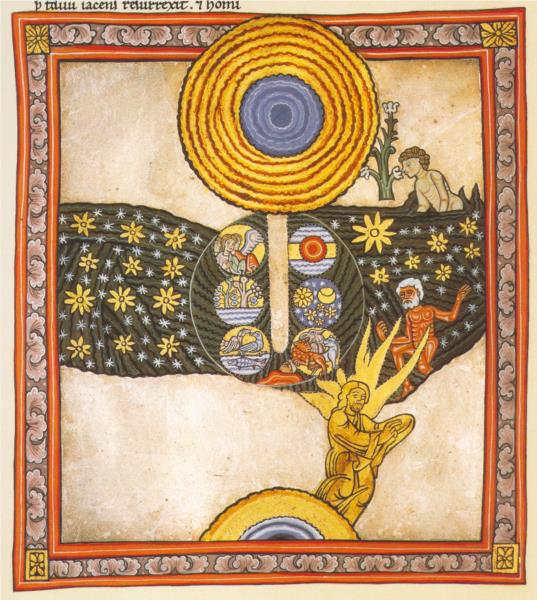

This is merely the science of self-organization and complex systems; however, it seems apparent that this dynamic system which is the living organism, can be seen just as we have described the cosmos heretofore as having a material aspect and a spiritual aspect. Within the organism is a sign of the two mysteries we have discussed before. We have the invisible whole seen as an organized network of information (heavenly) and complicated, visible, yet hidden reality of the unique existence of parts (earthly). In this very sense, the body, as we will understand is a place where heaven and earth are represented in the broadness of the whole and the minutia of the parts. The body as a whole is a microcosm of meaning, and it is made up of component parts (materials). The whole defines and orders the parts and the parts express and feed the whole.

We typically define “life” as biological life. However, if we see how biological life is the coming together of parts and whole, we can see biological life as a sign of Divine Life. Conversely, we can see how death is defined as the opposite. We define death most generally as the separation of body and spirit, or biologically, as the disconnection between part and whole, where the whole cannot have command over the parts and the parts do not work to sustain the whole.

Life and death, spiritually speaking, have a similar meaning as the biological understanding. In our experience, there are two ways things can be “dead” and we’ve discussed them in the last two articles. One is a world that is so ordered that it grows stale and mindless, one is bored of the dreariness of habitual life. This lifelessness is common in the overly developed world which has taken all serendipity out of everyday life. The other, which is more common in the ancient world, is the breakdown of the parts to no longer resemble meaning. Often symbolized in flooding or emersion in water, this “death” focuses on how the parts, the material fails to have any order derived from meaningful relations. Both types of death, however, co-occur; they are the same event of meaning and matter separating.

Death contains two opposites separated from themselves: anxiety and boredom1; in death the world is somehow both “without form and void” (Gen 1:2), connoting an emptiness and a chaos simultaneously. Life, on the other hand, is made possible in the separation of the heavens and earth, followed by the uniting together of material and meaning in the symbol of the body. The body is thus soil, which is transforming and unique potential (material), which is inflated with spirit (order and meaning). Life is thus a symbol of reality, and mankind is the symbol of eternal reality, the image of God. We are the “horizon creatures,” as St. Thomas says, who are made up of soil and divinity (Gen 2:7).

The Body as the Dwelling of the Holy Spirit

The first two articles spoke in a roundabout way of the two persons in the Trinity: the Father and the Son. This one is heading towards perhaps the most difficult to comprehend of the coequal persons of the Trinity: The Holy Spirit. I am here reminded of one of the names for the Holy Spirit in the Nicene Creed which is very relevant to this discussion: the Holy Spirit is called “the Lord and Giver of Life.”

In Genesis, the Spirit of God is present, hovering over the waters of the undifferentiated heavens and earth, before they are separated, making room for life to exist in an ordered world with dry, stable land (Gen 1:1-10). Subsequently, the earth is filled with living creatures. The Spirit is also poured out by the Father like water on the dry land. (Isa 44:3). The Spirit is what is given to the lifeless and barren to bring up life, to dwell in living things which shows the unity of heaven on earth as Life. And when the Spirit that is removed from life that causes things to die (Ps 103:29-30).

Insofar as we are alive in the Spirit, we can be a symbol of Life in the Divine Trinity. It is in reception of that which gives life, that which separates opposites and reunites them in sacramental unity, that we can be the sign of the invisible reality.

“The body is not made for sexual immorality, but for the Lord, and the Lord for the body… Do you not know that your body is a temple of the Holy Spirit?” (1Cor 6:12-20)

It is the uniting of the heavenly and the earthly which brings meaning, but it is when these things are at odds when meaning is lost and death comes. Our mission, it would seem, is to act through our body to reveal that which is invisible; in other words, regain what it means to be the image and likeness of God. St. Irenaeus in agreement puts it “the Glory of God is man fully alive.”

Not understanding this is the cause of the problem of epiphenomenalism. If we fixate on whether material or meaning is more real, we will neglect what it means to be fully alive, and we lose what we know to be the authentic mysteries of life: how uniqueness and universality come into a community of life and love.

1 Interestingly, this is the same picture that Mihaly Csikszentmihalyi paints for the balance required to get into a flow state which is a state of being most alive. Flow is activity which presses one to the edge of chaos, just inside one’s range of skill.