We often wander our way through life with little guidance. Our parents, friends, role models, and other people we trust have given us some good, explicit advice on how to live. Some of this advice is useful to us and some of it not. The advice we receive comes from a limited source: those who live near us in location and in time. And this advice comes from a generally narrow perspective on life. Our advisers may know only what has worked for them and may share that with you. Of course, practical living needs these unique advisers who know you well and have much in common with you, but for us to become aware of a richer perspective of life, we need to dig a little deeper.

But we have defenses when it comes to unsought advice. We tend to distrust those who try to give us advice without understanding our predicament, like in the way our loved ones might understand, or the way we understand it. We hate the idea that someone might have something to tell us regarding “how to live life.” Isn’t it presumptuous that this person thinks he knows how I should live my life? Are we not insulted by the idea that there might be a better way to do something when the way we have been doing it has been so dear to our identity? Like parenting, is there any greater taboo than to tell a mother what she should be doing differently?

Of course, we cannot take everyone’s advice seriously, but sometimes we foolishly think that we naturally know how to be a good friend, a parent, a teacher, a son or daughter. But we were all once infants thrown into this chaotic world, only to find a few tools to help us survive, and we stuck to those, and we expect them to work for almost everything. Without any outside advice, our options are narrow and stereotyped and ultimately self-limiting.

Living, as the Artist Paints

I want to argue that, with something as important as living our lives and our relationships, we should seek all the guidance we can get. But I do not suggest giving up on your instincts and not trusting yourself. It will be our instinct that is, in some way, the best—or only—critic for new advice. Ignoring what you feel can be equally negative. My suggestion is we live our lives in a way that an artist might go about her practice.

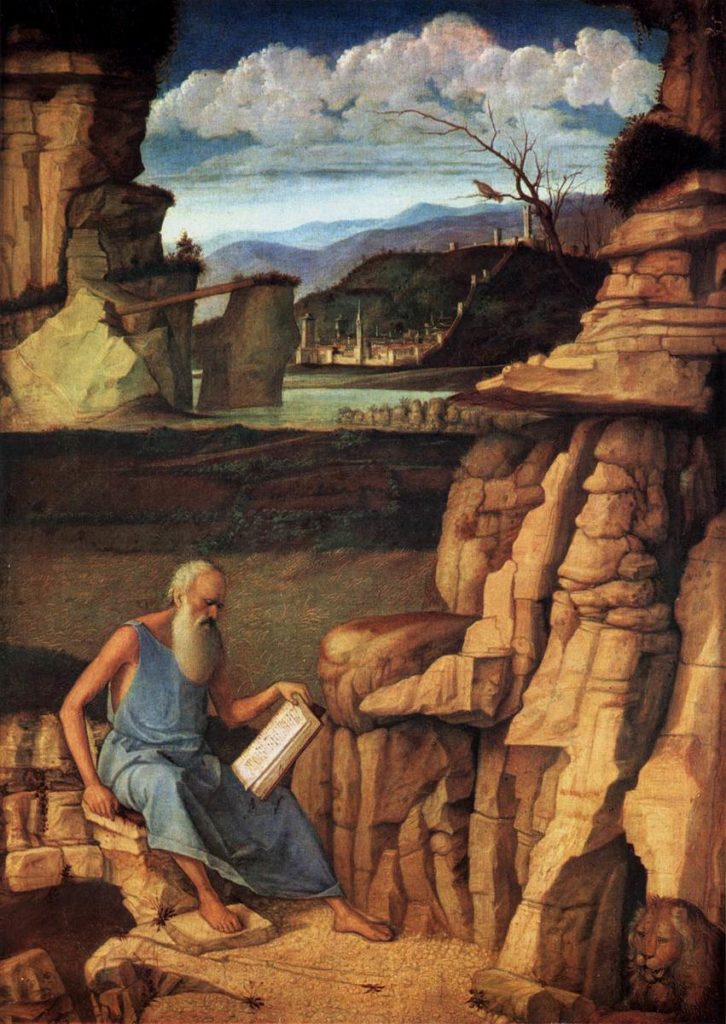

The artist is both confident in her own ability and her vision, yet she is humble and indebted to those who came before her, who defined the whole enterprise of her art. What it takes to make life an art, so to speak, is to recognize the history of ideas that make up the essence of your journey. According to Erich Fromm, art is the culmination of “theory and practice.” We practice life all the time, we really have no choice, but, whether actively or passively, we’ve been practicing the same old tricks. An artist will challenge herself, finding new influences and playing with new ideas and techniques. Immersing oneself in the theory can help us make our practice more intentional, more art-like.

Where Do We Get Advice?

How does one learn theory for life itself? Who can we trust?

Fortunately for us, there are more than two thousand years of distilled advice that survives today because it is still somehow relevant. Ideas on the important things in life, seem to have been focused on for all the time human civilization has been around.

The surfaces, i.e., language, culture, politics, and some external values, have changed over the millennia, but the essential needs of a human being has stayed the same. After all, we are the same species with the same psychological hardware as those that built the pyramids. This is why people still can learn a lot from reading Plato and feel an authentic human spirit by looking at ancient cave paintings.

The Essential, According to Time

Over the last two thousand years there was devised—and written—several ideas about how to live a good life and how to fill the roles we are given. Many of them were forgotten, but a few of them, which withstood the test of time, can still be used today.

We must look at the roles we play in life and trace them back to see how they compare and differ from those of history. Some roles have been the same. For instance, parenting, friendship, leadership, and mentorship are practically essential to human life, but others have changed so greatly that there is little comparable to them in the past, like the accountant or the high-school sports coach. But we can look at the history of these things and realize that they come from more universal archetypes. The sports coach can be like a father who inspires and teaches his children. The accountant like a learned advisor who must know the values of whom she advises.

There are tomes of history on all these topics that have been important to humanity since its dawning. There are traces of it in books and media today, but usually only what is popular opinion in that particular time. Although advice from today’s writers and speakers can be more accessible and more applicable, they do not give us insight into what is essential about the advice. We usually do not get the variety of ideas that encircle the essential subject we are focused on. We cannot know our full role as a teacher unless we see the relationship of Socrates to Plato, for example. What is culturally accepted is the only option. Tracing ideas through history can teach us what life (including our roles in it) truly means.

Tradition

Not only can we get a guide for what is essential for human life, i.e., what has been universal since the beginning of civilization. But we can also learn the roots of our culture, and this is important because some things are almost entirely based on culture. For being a parent is both essential and culturally defined. We were all born to parents, but parenting styles a culturally defined. In Childhood and Society, Erik Erickson gives us examples of the variation in a simple aspect of parenting: feeding. Just to prove that although there is something natural about it, much of it is cultural.

“While it is quite clear, then, what must happen to keep the baby alive (the minimum supply necessary) and what must not happen, lest he die or be severely stunted (the maximum frustration tolerable) there is increasing leeway in regard to what may happen”

What looking back on history can do is to bring up all the possible ways life may be lived. Looking at the history of a tradition helps us to see the roots of the culture that touch into the essential. By seeing the possibilities in the tradition, and what has remained core to it, we can see what good practice can be. When today’s painters fall in love with everything between Leonardo and de Kooning, they recognize all the possibilities they can accomplish in their own work.

The poet Mary Oliver says in A Poetry Handbook that even though we don’t see poems in metrical verse too often now, we must still read and understand them, for they are where all poetry has come from and they are the backbone to a poetical mind.

“The truly contemporary creative force is something that is built out of the past, but with a difference… To be contemporary is to rise through the stack of the past, like the fire through the mountain. Only a heat so deeply and intelligently born can carry a new idea into the air.”

Oliver, in supporting the need for an appreciation for history, has given us insight into how to use it—by applying it to the mind through practice. She goes on to say that imitation is the best way for us to learn from the past because practicing more deeply affects the mind. Imitating the great poets creates a poetical mind that is intentionally made from the best writers in the tradition, rather than one accidentally made by circumstance.

“I think if imitation were encouraged much would be learned well that is now learned partially and haphazardly.”

How Life Becomes an Art

Art requires “theory and practice,” says Fromm. Theory can be found in great books, or even ok books which offer a lot of practical advice. Both might be needed for we have the challenge of turning the abstract advice into practical action. Studying theory makes no difference unless it is practiced or imitated, and practice is blind unless it is guided by theory. This is relevant to anything we may do in life and has been categorized under a single heading: philosophy (or at least according to how I see philosophy).

By accepting this argument, life becomes an art. And you and your community and your world are the canvas. Your thinking changes about the roles you play; you begin to see, in greater detail, the tradition behind your actions, and then they become more deliberate, and eventually more intuitive.

Just as a painter studies the techniques and the theories of Cezanne and Monet, a parent studies theories of childhood development given by psychoanalysis and behaviorist, a manager studies what it takes to lead a group from ancient times to present day, a husband studies what it means to love from the romantics and the realists and the Christians. In doing this, we find our essential humanity without forgetting our historical roots.