Empathy, or putting yourself in someone’s shoes, is usually described as a good attribute to have or rule to follow, and despite reasonable criticisms, it really can be. But empathizing with others is more than a neutral act, it is driven by social motivations and can pose problems which the critics of empathy know very well. They say that the danger comes from our picking and choosing of who we empathize with and our empathizing with people that hate and feeling that hatred. But an existential problem comes from our ability to try understanding others. This problem is that there are other minds in the world and they can conflict with your view on the world.

This might not seem terribly connected, but how we see truth, and how we accept others’ truth can be a centerpiece in our lives—where empathy can divide the world or draw us closer. Through empathy, grappling with the truths of other’s thoughts becomes how groups form, how you judge others, objectifying them, and being objectified yourself. And it has to do with who you are.

Learning Theory of Mind

Starting to learn what people know and how it effects their belief system and behaviors happens early in life, around four years old. We learn to attribute people’s behaviors to the belief system they have, the information they have received, or the emotional situation that they could be facing. This is around the time when we gain a fuller “theory of mind.”

To illustrate what is meant by theory of mind, one study has become a classic example in psychology. This study showed the age at which children began to learn to understand that other people have different minds which have contents based on what they see and not what the child knows. Realizing that others can have false beliefs is understanding that there are separate, thinking minds. The experiment is known as the “Maxi doll experiment.”

In the experiment, a younger child is put into a situation where he or she sees a doll put some chocolate into a drawer. When the doll leaves the room, the experimenter hides the chocolate somewhere else. The doll returns, and the child is asked where the doll will first look for its chocolate. A child who hasn’t learned that others have separate minds will say that the doll will look in the new hiding spot because that is where the chocolate is. The child is mistaken because he or she does not realize that the doll believes something that differs from the child’s belief. However, an older child around age four will be able to imagine where the doll thinks the chocolate is, even if the doll would be mistaken.

From this point in development we begin to understand, or at least have explanations for other people’s behaviors. We can see the actions of a person and commit to the idea that they must be acting rationally according to what they accept as truth and the truth of their emotional experience. In fact, we do not hesitate to explain behaviors, even the strangest act are given a set of beliefs which we can understand and sympathize with. After all, for us to try to understand another person’s actions we must be able to relate to our own belief system and emotional landscape, to whatever makes us human.

However, that is not always the case, sometimes we can believe someone is fundamentally mistaken. This is a social issue, not an intellectual one.

Theory of Mind Is an Emotion of Affiliation

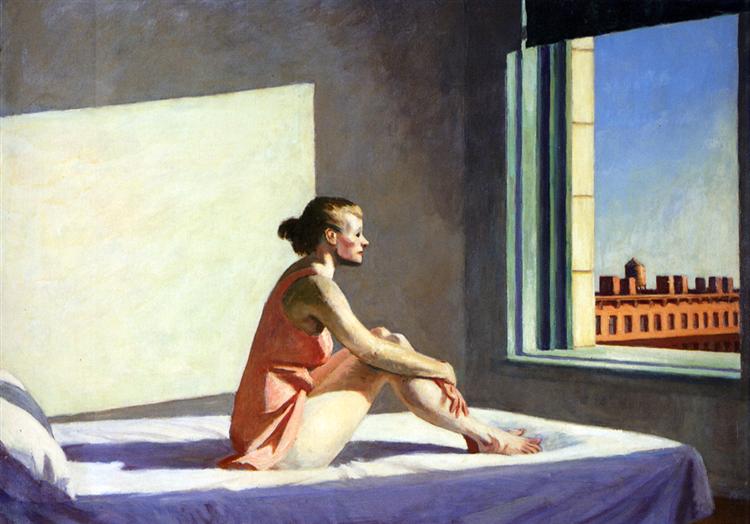

To put yourself in another person’s shoes is an act requiring self-consciousness. You must remove yourself from your own present and think in a logical manner about what the other person could know or feel based on how you perceive their situation.

For us to be self-conscious and unsure of ourselves in front of other people is for us to believe that the other person might know a truth which we do not. Other minds open us to the possibility of being wrong. And we feel self-conscious. But more often than that, we are actively judging others. Judgements of others and your judgements of yourself are very intertwined, but for now I will look at how we judge others—something we are more familiar with.

When we cannot justify someone’s actions as having a valid place in your scheme of rational action—we cannot sympathize or identify with their reasoning—we are committing a social act. We think that this person is fundamentally mistaken. This person must not simply lack facts or data or are being accidentally misunderstood. They are simply alien, and in our judgement, we treat them that way. But we rarely end up taking this route and concluding that someone is totally unrelatable in their actions. If we make a sufficient effort, we will see that there is something relatable, something human in anyone. Looking hard enough, we usually see their mistakes or where their belief differs from us, if we are willing to put the effort into get to know the person and giving them a charitable reading of their explanations. This is why it is a social act, because it is a matter of how much charity you are willing to give this person.

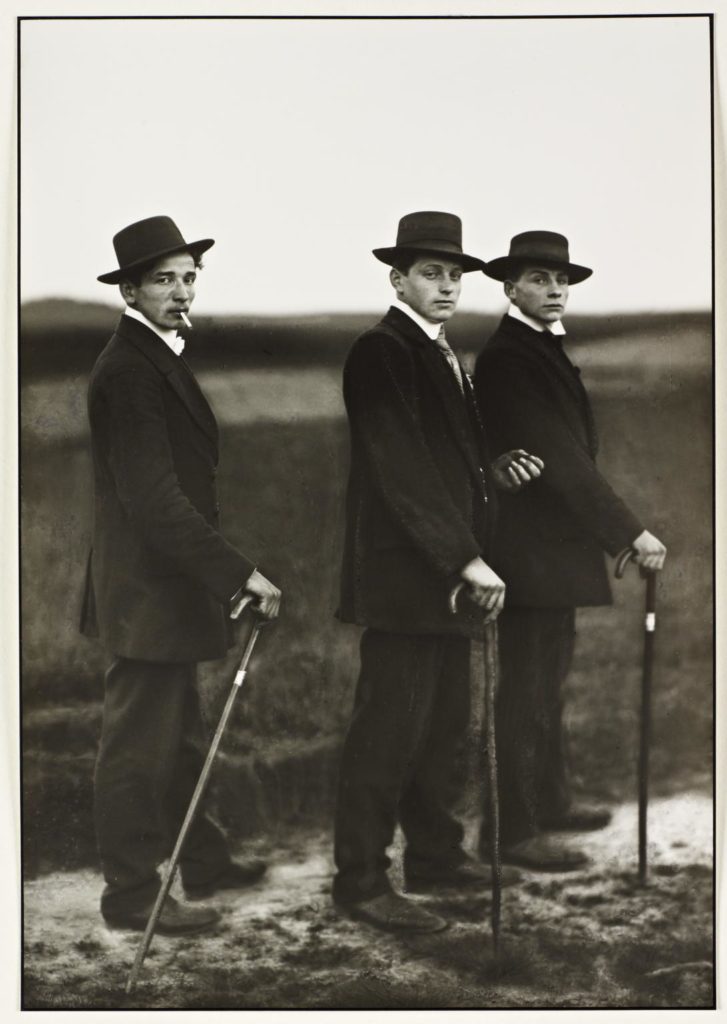

But often we do not even start on the charitable side. We usually notice the “essential” difference and then assume their actions based that difference. We notice skin color and explain their actions according to what a person with the skin color usually acts. We notice what group they are in and explain their behaviors with that as the answer. We do not even see how we could be the same as this person because we notice their unique trait and pretend that that is just what that person does. When we think, “that just what that type of person does,” we keep ourselves from relating to them. Our ability for real theory of mind gets precluded by our notion of how the other person is essentially different.

Empathy and Theory of Mind

The question becomes who do we try to understand and who should we peg as other, as wrong? Is that even a valid question? Can we make conscious decisions about who gets our understanding? We are all human beings, right? Everyone should be able to ignite some empathy within us. Or are some of us not worth empathizing with because of the evil acts? Are these people overly pained by something relatable and human? Would understanding help?

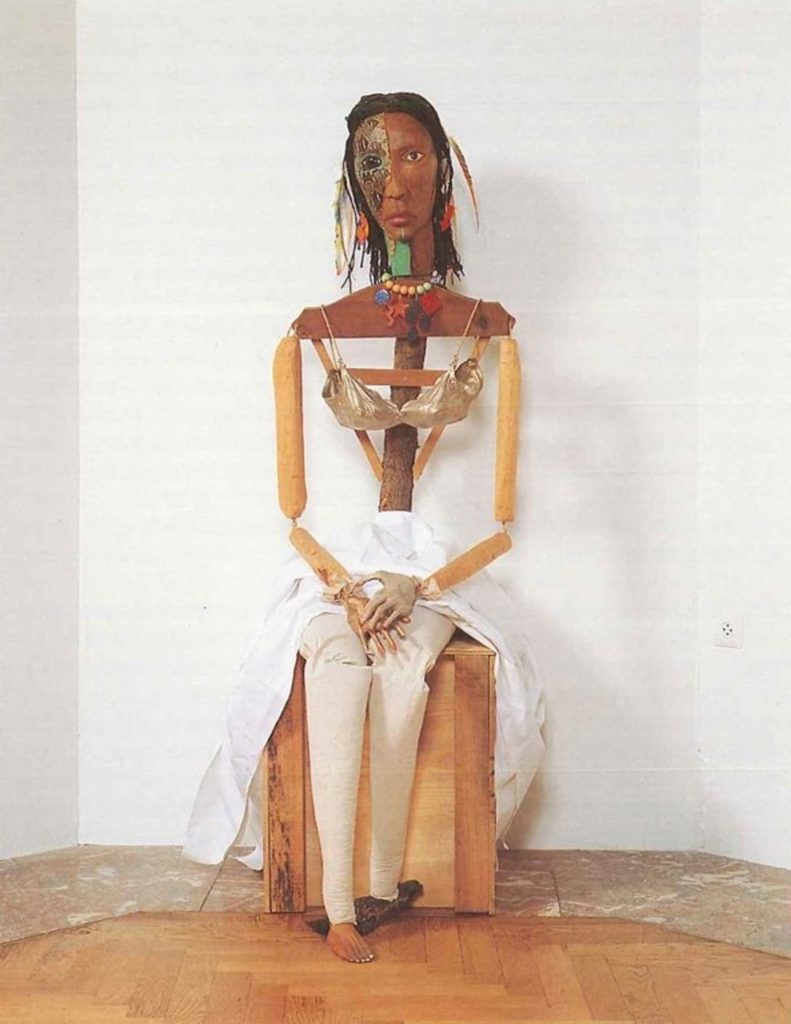

I think that we ought to see the humanity in others first, before we condemn them. This way we can see the honest misstep they took, or we can see how their experience got them to their current position, before we simply say that they are fundamentally wrong. I do not think we should leave people totally out of the possibility for understanding. Yes, there are evil people, who may not deserve kind treatment, but we can at least try to sympathize with what went wrong for them. Is there any other way to prevent other people from going down the same harmful path. If we truly cannot find all the pieces of humanity in someone then maybe they can be exceptional.

The adage that “an enemy is just someone that we do not yet understand” is certainly applicable, and could be a good piece of advice. But it needs to be revised, for it is naïve. I want to add that just because you sympathize and understand someone does not make them free of their faults, and it does not mean they do not deserve punishment. But you ought not make them, the persons, your “enemy.” If evil is being done, even an evil from the most innocent and naïve causes, which we can sympathize with, that problem is still a problem. We may never be able to repair the souls of the evildoers, but we can do everything we can to stop more from joining them and lessening their delusion.

I propose that we first look at what makes someone human, because that is what can drown out the evil that they commit. The evil is the enemy, not the person, not the human being. Dr. Martin Luther King Jr. had the same sentiment when describing agape loveas a tool for fighting racism.

“Agape means nothing sentimental or basically affectionate; it means understanding, redeeming good will for all men, an overflowing love which seeks nothing in return. It is the love of God working in the lives of men. When we love on the agape level we love men not because we like them, not because their attitudes and ways appeal to us, but because God loves them. Here we rise to the position of loving the person who does the evil deed while hating the deed he does.”