Have you ever been unable to describe to someone what your experiencing? Not simply because it is so complicated or the person you are talking to just won’t understand, but because the only way to describe that would be to put that other person inside your hear to relive that moment you want to communicate.

There is something about your experience in life that is not quantifiable, not conceptualizable, and ultimately cannot leave your own subjective experience. It is especially not transferable to another human being or even to yourself after the moment of that experience has passed.

“It seems as if the elementary psychic fact were not thought or this thought or that thought, but my thought, every thought being owned.”

William James – Psychology: A Briefer Course

What is owned, and what must be owned—can only be owned—are the subjective qualities of our experience. They are owned only for fleeting moments; they are our sensations, sights, sounds, tastes, etc.—they are qualia.

Qualia are what philosophers call the subjective materials that makes up our experience. It is what we, as individual subjects, experience, separately from everyone else. The particular feeling of your pillow, the particular taste of your coffee, or the particular sound of a voice, are qualia, but not in the abstract or physical way, but the experience itself, without borders, and without definition. Qualia make up our what-it-is-like-to-be-ness.

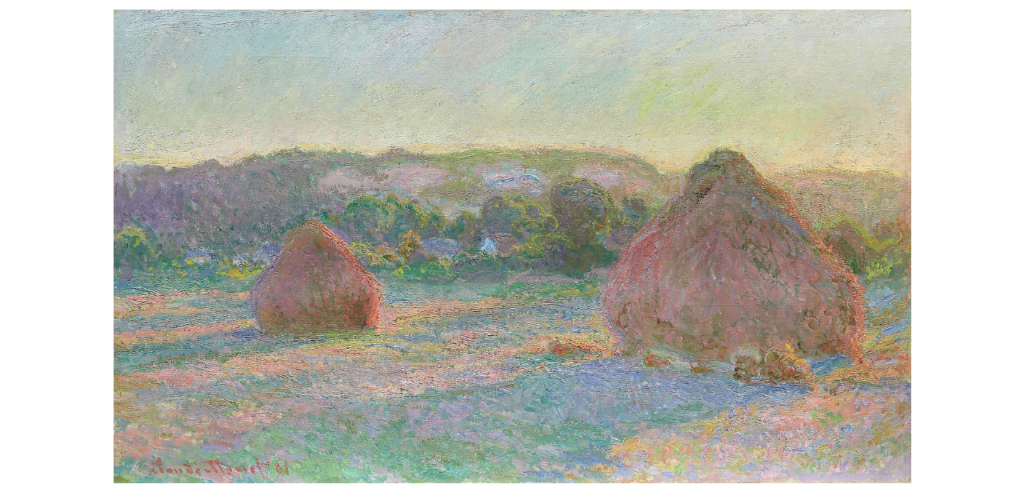

Color

We commonly use the example of color as a quintessential example of qualia. Although it is a useful example to start with, particular colors are not qualia. They are concepts. Qualia go deeper.

For example, the color “red” is a conceptualization of qualia. There is no spot on a spectrum where red starts and ends, though we speak as if there is. It’s that color that we see, on our own, and other people who see it, on their own, in their own way, which we have come to agreement to call “red.”

The redness we see is dependent on the contrast with its surroundings, not necessarily on its actual physical properties. There is no physical property of the qualia of red as we know it. We know it as something seen. The quality (or qualia) of redness is only to be experienced in you or I’s present perception, even if it cannot persist longer than that moment.

I am usually reminded of the dilemma of qualia when I think about red-green colorblindness. The people with this colorblindness cannot see the difference between reds and greens if the other color properties (saturation, brightness, etc.) are all the same. To me, this is a totally a foreign thing to imagine experiencing—the qualities of the color concepts are so distinct in my subjective view. How can they be mistaken for each other?

This hints at what qualia, those incommunicable, totally internal, subjective experiences are. Colorblindness says to me that our visual color pallets need not be all the same, as long as they contain more or less the same patterns of distinguishing between what our sensory organs pick up. I don’t care exactly what it looks like from your point of view, because as long as there are shared patterns of distinction, we can communicate what we see. Our problems may be limited to whether the sky is cyan or turquoise. But for red-green colorblindness, because it disrupts the pattern of distinction, can actually result some consequential differences in perception.

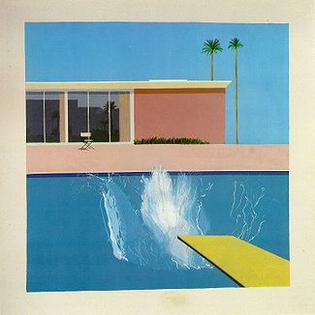

Meaning Is Within Subjective Differences

The qualia we experience can be totally different from everyone else’s, but as long as the patterning of distinction is the same, you can go on functioning like a normal person. Imagine, all of the sudden, seeing in inverted colors, but once you are used to it, you can function just like everyone else, and communicate with them. Soon enough you will start calling black “white” and cyan “red” and easily understand what others are talking about, and not be blind to any perceptions. No significant difference in your interaction with the world will happen.

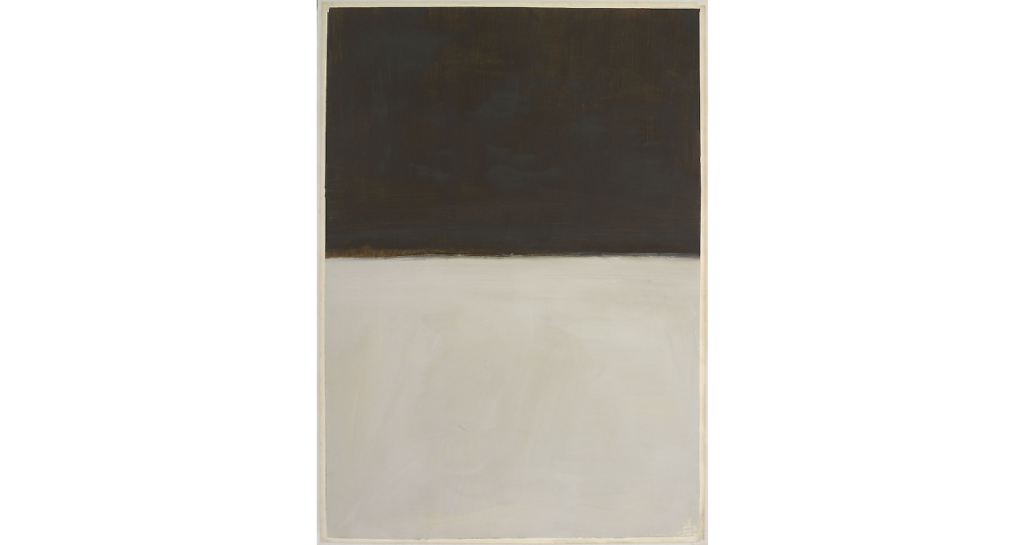

Perception is dependent on the contrasts of sensations to create meaningful things in the world. The person with inverted vision will perceive like everyone else, where the red-green colorblind person cannot.

“What we hear when the thunder crashes is not thunder pure, but thunder-breaking-upon-silence-and-contrasting-with-it.” – James

William James – Psychology: A Briefer Course

If our ears could not discriminate between silence and thunder, we simply could not perceive thunder. We could still sense it, but it would be meaningless. It is our senses which detect important changes, not things in themselves. For all the sensory organs are ignoring plenty of stimuli, not because they are not there but because most stimuli do not contrast in any meaningful way to direct our attention towards.

When these differences in qualia are learned, we do not need to very closely at qualia again. Instead of mere sensation, we perceive. We see the border of an object instead of the sensations contrasting sharply, or rather, we see the whole object. We learn perceptions, and as we use them, we can ignore the qualia that had once given rise to them.

The Unique Moments of Qualia

Is there anything lost when we ignore qualia?

It is only within an organism that perception can be created from qualia. It is only the contrasting qualities of light or smell or sound or any combinations of senses that make things meaningful. Building the perceptible world from the ground up only happens in a single, present, conscious individual.

Words and symbols help us share a consciousness, but the very initial connection to the world through consciousness is what we must learn on our own, through qualia and the distinction between sensations. The world you build from the ground up is totally unique, incommunicable, and true to the very core of your personal truth, unspoiled by outside influence or assumptions.

Accessing qualia is not as easy as it might seem. The qualia of a moment cannot even be carried beyond the moment it is sensed, we must sense them now as they arrive. Once it passes, it is gone, it is impermanent, and new qualia are now present. We truly, as Heraclitus said, cannot step into the same river twice. To our human experience, nothing is the same besides the concepts that we give to moments that seem similar or important enough to group. Those concepts exist to us through time, and convince us that our experience lasts, and is stable, through time. Like “red,” they are stable, but the qualia hardly stop for a moment and are gone.

We wish for a stable world, but the stream of consciousness continues, and we cannot stop it no matter how much we group the world into its essential and lasting things.

Observing passing qualia is something of a pastime—after you see the border there is no need to look closely again at where one color slowly bleeds into the next. Seeing a relatively stable thing can help us survive, but what have we lost when we stop paying attention to qualia?

The Philosophy of Observing Qualia

We have lost something that cannot be communicated. What we lost is whatever is signified by all the signifiers. So, it cannot be named. It is experience without concept. It is what brings us to the feeling of presence and impermanence.

Marion Milner, in On Not Being Able to Paint, writes about her discovery of qualia:

“Here also were certainly two different ways of feeling about experience. One way had to do with a common sense world of objects separated by outline, keeping themselves to themselves and staying the same, the other had to do with a world of change, of continual development and process, one in which there was no sharp line between one state and the next, as there is no fixed boundary between twilight and darkness but only a gradual merging of the one into the other. But though I could know, in retrospect, that the changing world seemed nearer the true quality of experience, to give oneself to this knowledge seemed like taking some dangerous plunge; to part of my mind the changing world seemed near to a mad one and the fixed world the only sanity. And this idea of there being no fixed outline, no boundary between one state and another, also introduced the idea of no boundary between one self and another self, it brought in the idea of one personality merging with another.”