We often debate about what qualifies us as being self-conscious. And we often wonder whether or not an animal like an ape or elephant or dolphin is self-conscious, and how do we know? It is a very ambitious question to ask considering most of us mean very different things when we say “self-conscious.” And if we do not understand exactly what it means how can we know what makes us self-conscious—let alone having the ability to detect it in other animals or even other people. But understanding self-consciousness is very important simply in creating a capacity for self-knowledge.

The First Skill of Self-Consciousness

I think that the self-consciousness, as we typically define it, is a combination of evolved skills and traits that add up to something unique to humans. Many animals can have some of those skills but without all of them, they do not seem to have the full self-consciousness that we have. One of these basic skills stands out as essential in creating self-consciousness.

In defining self-consciousness, it is worth mentioning a skill which is so fundamental to self-consciousness that we cannot think of it without speaking in terms of the skill. From this basic skill comes all the complex, confusing, contradictory things that happen when we think of ourselves. I am talking about our ability to abstract away from the present and find meaning in objects that redefines their motivational properties as relevant for a future time. A hammer means more than the inert object that it normally is; it can be thought of as something not yet important but potentially useful.

This is a skill that some primates have. Some see the potential of a tool is when they use a stick to move a banana closer to the cage so that it can grab it. To treat the stick as an extension of the body, to create a tool out of it, is abstracting for a future goal.

We Are Abstracted Ones

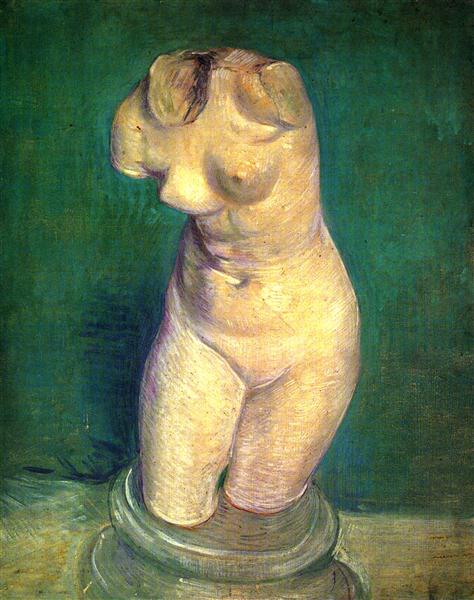

Although we can talk about the consequences of this ability to use tools, we shall look at what happens when we observe ourselves and see us as a thing in the world, and ultimately abstracting what is our own flesh and blood to be something other than its present “I”-ness or subjectivity.

When we describe ourselves, we are conceptualizing ourselves as a tool for a future good. And thus, we have value attributed to ourselves that is more than the primordial pain or pleasure or other subjective phenomena. When we see ourselves as an observable object with observable behaviors and thoughts and feelings, and we can abstract from those an added meaning. We label our personalities and skills and citizenship because these things have values which may become in the future, especially in social situations.

When is it that we start to observe these aspects about us? And is this period in development significant? To answer these questions, I will invoke a popular experiment which is thought to test some aspect of self-consciousness, specifically the ability to see ourselves as an object connected to our subjectivity.

The Mirror Stage

There is much speculation on the significance of one of the most well-known tests in psychology of self-consciousness. “The mirror test” is often conducted using either infants who are approaching a new phase of self-consciousness or animal which could show signs of higher-level thinking. It goes as follows:

The experimenter places a colored chalk dot on the forehead of the subject in a way that is not detectable. Next, the experimenter presents a mirror for the subject to look into. If the subject recognizes itself in the mirror, he or she will be surprised or curious and wipe the color dot off the forehead. If the child has not yet reached the phase of development, he or she will not notice anything surprising, presumably not realizing that they are seeing themselves in the world, that it is the subject staring back at what is the object that comprises the subject.

This test tells us whether or not a person or an animal is able to recognize the fleshy boundary that separates mind from the world. It is the learning of an infantile mind-body dualism. We learn to recognize the object of ourselves after having shortly lived a pure subjective sort of existence.

Introspection

Like the experiments with mirrors, there is also experiential evidence when we see how difficult it is for us to introspect or understand exactly how we act towards other people. Sometimes we act nicer that we think we are, or meaner. We often have no idea how we appear to others and we can only see so much of who we are when we are focused outward on the world. In some ways, we still remain unself-conscious when we do not recognize the metaphorical mirrors that other people provide for us.

When we realize the observability of our bodies, behavior, feelings, and thoughts, we can abstract from them many meaningful things. We do this whenever we introspect or think about ourselves through some other’s eyes. Everything in psychology that we apply to our lives is an abstraction from the mind, and all these aspects we conceptualize receive a new sort of value, a value of longer-term benefit. This is where psychology can be very helpful when we are self-consciously trying to understand ourselves to benefit our relationships or careers.

For instance, terms like pain, normally aversive, can become a badge of toughness, or something to ignore when competing in race. The “things” that we feel become more than their appearance, or sometimes less. In the case of a strong romantic attraction to someone unavailable to you, you may deny your feelings because of the long-term consequences that make you save your attention for other things. The person represents someone not of interest because it is beneficial to long-term or social goals to ignore that love or lust. This usually starts as a reason and then gradually even the feelings for that person dissipates.

Significance in Development

One reason it is worth understanding the mirror stage in its place in development is that it can affect how we see ourselves today. The mirror stage is early in development and this is important to note because it comes at a time before complex language (usually between one and two years old). This means that much of the things about us that we attribute meaning to, are not easy to recall or understand because they became habitual before we had the language to describe them. Yet symbols and behaviors and people can become part of who we are without us ever being able to articulate and remember them.

It is also significant because situation we are given at this period of development is marked with dependence. At the time we begin to recognize ourselves as an object (with potential usefulness), we are completely dependent on our caregivers. This dependence influences the understanding we make of ourselves. We learn that we must depend on things and people. We discover what we must do to get our way and survive, and we discover whether we are generally good or bad.

Forming an idea of the self happens at such an early age that these things would probably appear strange to us if we learned what makes up our self-image. That is why Freud’s theories can sound so far-fetched intellectually, but they sometimes appeal to our intuitions. There is no way of knowing what forces impact the idea of who you are when you were a small child. Yet it may be helpful if we did discover them. We might discover where our self-defeating limitations and pains are coming from.

Who we are is hidden from us from what has happened between the mirror stage and when we began to learn language and retain memories. The forming of ourselves as people happened in this time, and the job of psychoanalysis is to discover who this person is and what self-beliefs are there to form anxiety or depression or much more severe and strange symptoms. It is that first discovering that you are a thing which can be thought of abstractly and transformed into something of value for another time.