What makes humans different from animals? One can list many things, but ultimately the most significant answer comes as a major shift in our ability to think using representatives of things which are not present. We have the ability to think outside the present situation. We can use the tools of explicit memory and language to imagine the future and the past. Using this ability practically, allows us to act more “intelligently” to achieve long-term goals. Despite the simplicity of this ability, it is the common denominator of many of the mental abilities that separate us from other animals.

To be able to imagine, using symbolic thinking, a possible future and its symbolic requirements, means that our experiences can be reinterpreted as being a map to or away from this future. Our experience becomes more than what it was before: paper has much greater emotional meaning when it has important writing on it. To be able to imagine what it takes to become a doctor would help you interpret all of the schooling as a necessary struggle to reach a higher goal.

An animal which exists according to the present, cannot imagine things symbolically and must see and deal with things as they are, moment by moment as they are conditioned to deal with them. Instincts have given animals an almost lucky ability to do what’s best for its long-term well-being. But the animal is not conscious of the end, nor the means to achieve it, they are merely things to be acted on. For the animal the good is in the action.

One of the products—a byproduct even—of this mental ability is the creation of self-consciousness, followed by then the creation of the concept of the “ego” or “self.”

A Symbolic Self

The things that are symbolic landmarks of the path to a long-term goal begin to only have meaning with respect to the goal. Things become essentialized, gain value, become useful or not based on how they fulfill this future oriented goal.

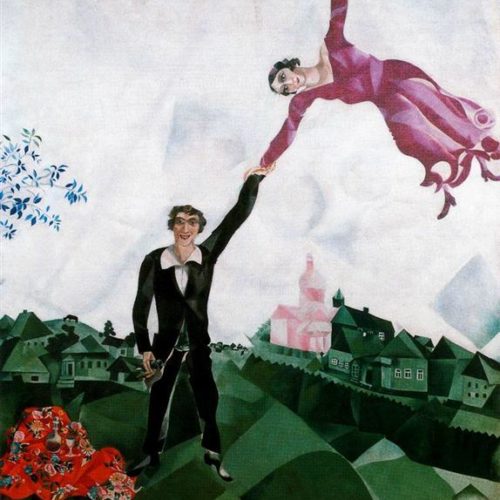

For us there is a single variable that always exists in the seeking of abstract goals. We see purpose in animals’ behaviors, but do not imagine the symbolic goal like we do. They do not pretend that money is the route to status, they do not aim at something, other than the instinctual thing. The ego can do this. For us to strive for a goal, we must manipulate our body as a tool for accomplishing another goal. And for us to accomplish a goal, the hope is that when we reach it, it will be this “me” that is there, we must imagine some image of ourselves accomplishing the goal if we can conceive of it to begin with. The ego or the self rests on the ability to symbolically represent the world and to strive in that world.

In this way, we have made everything that is so intimately tied to our existence a symbol and a tool for something that does not yet exist, an abstract goal. Not only is our perception of other things made into a means to an end, but the perception of our own bodies, our minds, and even our perceptions themselves become part of the symbolic order of seeking certain abstract goals. We resist temptations, we avert our eyes, we reject our thoughts, we distrust our perceptions, all in the name of some distant goal.

All that we call our identities, abilities, and desires are all symbolized and made into something that has goodness in its relation to another end. Whatever can be symbolized about you, word or image or gesture, becomes something of a tool for the instinctual goal that was symbolized, that you can imagine.

Attachment to Selfhood

We use our “self” or ego especially as a tool of consultation. We bring back the stories and representations of our histories to decide what plans of action we ought to take and whether we can even succeed. But like any tool that is used for another cause, the consultations of the self can be over-relied on. Instead of listening to the present moment, we fixate on what we “should” be striving for, what the self and its goals are. When we look at ourselves within the framework of a symbolic order which strives to goals, we see ourselves as having unalterable abilities, purposes, and desires. We define these for ourselves and rely on those features because they fit so well in our symbolic universe. We consult this symbolic order when, all in all, it does not know our actual limitations, our desires, and our purposes.

For instance, when I am feeling lazy, I consult the self-belief that I am a “writer” therefore I must act like one and start writing; I have a symbolic goal of “writer” to achieve, I know what actions represent its attainment, and I do those actions. This can be a useful tool to get started, but it can also be a dishonest way of limiting myself to a single form of expression. Or it can even deny my responsibility to choose my actions; I could easily claim “I am only a writer,” when some urgent action is necessary but which I do not wish to get involved with it. I attach myself to the self-idea and avoid shouldering the burden of a totally free choice.

To use our experience as a means to another end, a future end, or rather a future experience has implications in what moment we are truly living. How much can we really be present while self-conscious?

Being a Means and Not Being Present

First, there is of course the lack of presence we have when we perceive the things in the world as means to an end, as symbols of your own path. When we see a paper as a means to a specific end, we deny all of its other qualities, we are not present to its existence. But the effect is much more pronounced when it is you yourself that is the means to an end. When you become the instrument for another goal, the present moment is subordinated to a possible future.

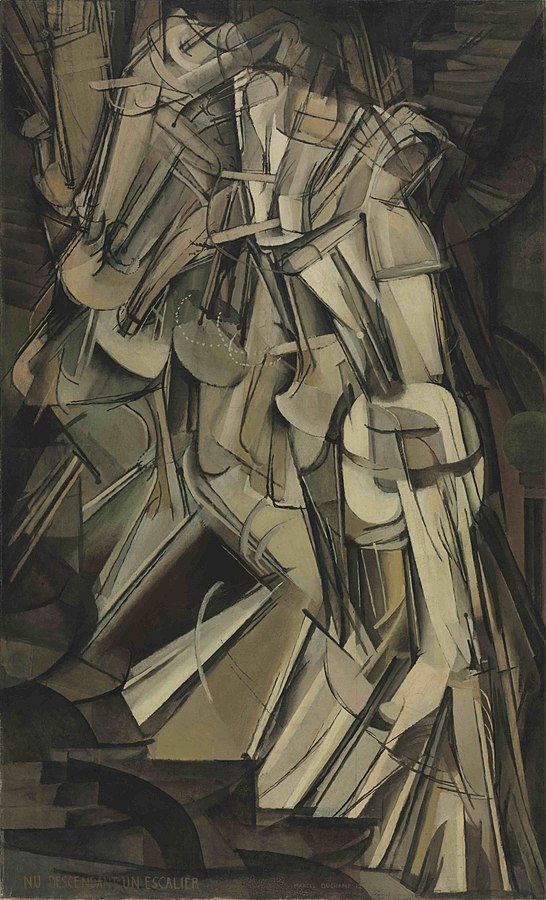

When using a hammer, we are in waiting for the real moment when we can enjoy the finished project. We are also waiting to get into the present moment, we ourselves become the tool which cannot rest in the present moment. When using tools, we use ourselves. Ultimately, we seek a symbolic goal.

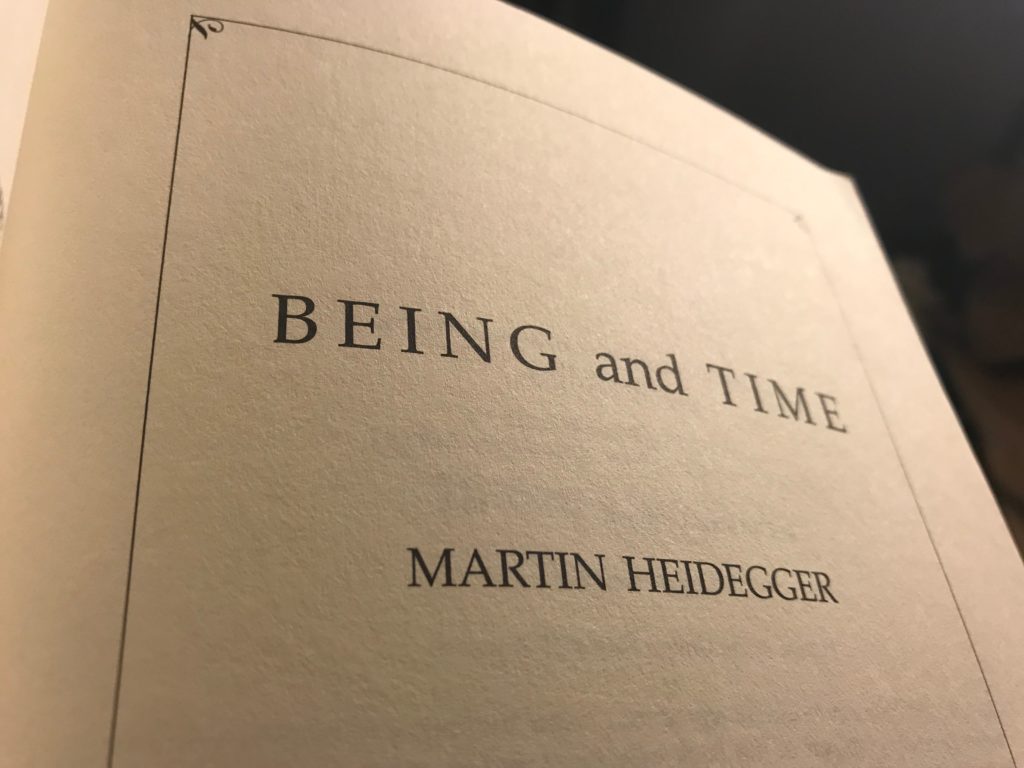

Michael Wheeler, in his article in the Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy, writes, “Heidegger claims, not only are the hammer, nails, and work-bench in this way not part of the engaged carpenter’s phenomenal world, neither, in a sense, is the carpenter. The carpenter becomes absorbed in his activity in such a way that he has no awareness of himself as a subject over and against a world of objects.”

When the symbolic ego-goal is to “be a good parent.” We often look to the signs of that to work towards them. In our ego-derived mission, we treat our children as symbols of our success, and we live removed from the actual experience of our kids. We aim to directly at our goal.

The present is subordinated, and what you do has no morality besides as an instrument for another good, the abstract good, which can be dangerous or stupid. One finds, when looking at the most horrible things people have done in history, that it was not a sick desire for evil that motivated disgusting behavior. It was the subordination of the present to a “higher,” abstract goal.

We subordinate the present often by—or while—suppressing an emotion that does not appear useful in terms of a route to your abstract goal. This can be useful in society when we bite our lip instead of talking back. To be focused on the goals of the ego is to be removed from the present, which takes energy, or willpower. After all, our natural impulses still try to tempt us to follow them, but a properly trained and motivated ego can virtually remove us from any difficult moment. Just consider the amazing endurance of those driven by a narrow purpose. It is difficult to resist pleasures unless the distant goal is very rewarding. And likewise, it is difficult to be present when the reward of removing oneself is such a good defense.

We cannot say whether the ego is good or bad, but we must learn how to be present as much as we must learn self-discipline. If life cannot be at any point authentically enjoyed, then we negate positive values, we become hollow with goals that we press towards without knowing how to embrace the journey.

We all know that the best projects are the ones which have positive long-term results but also that are enjoyable the whole way through. Ideally, if our life is a project, that is what we must aim at. And as I look around me, we have the extreme division of this. Where people elect for simple hedonistic pleasures to facilitate rest, and at the same time have jobs which have an order which one must always be divorced from the present. Many of us live in these extremes.

To exercise no-self is to react to a person without interpretation of their actions as being toward you and your personal goals. Imagine looking at a hammer for the first time, no knowing what it was for. That is the world that helps us release from the world of means, so that we can create our own values.