Let’s pretend we can sort people into two groups. There are those who see themselves as independent, as not needing any relationships for comfort or approval, but can also be cold and uncaring. And there are those who know and fully understand how much they psychologically depend on close, emotional relationships. They put a lot of effort—sometimes too much effort—into keeping the connection and emotional report between them and those who they are close to.

If the world could truly be divided into these two types of people, we would find that both of their perspectives on life could be justified. Happy lives tend to have close relationships in them which require care and effort, but it would not literally kill you if you lost them.

The side of relationships as unnecessary seems more like cold-blooded rationalism because we can always give a reason for why we never needed that relationship that recently went sour. For this person, relationships are peripheral to life; having relationships is a leisure activity. This person, I believe, is in self-denial, they use the non-necessity of relationships as a reason for why his or her relationships are not going the way they want. I think that no matter how you deny your involvement in relationships, you are still complicit in your concern for them.

One basic aspect of relationships that will show us how important relationships are to everyone is the quality of being recognized by others. From wanting the be the center of attention to wanting to shyly slip away into the background, the attention we receive is programmed into our psychology, and we cannot deny it.

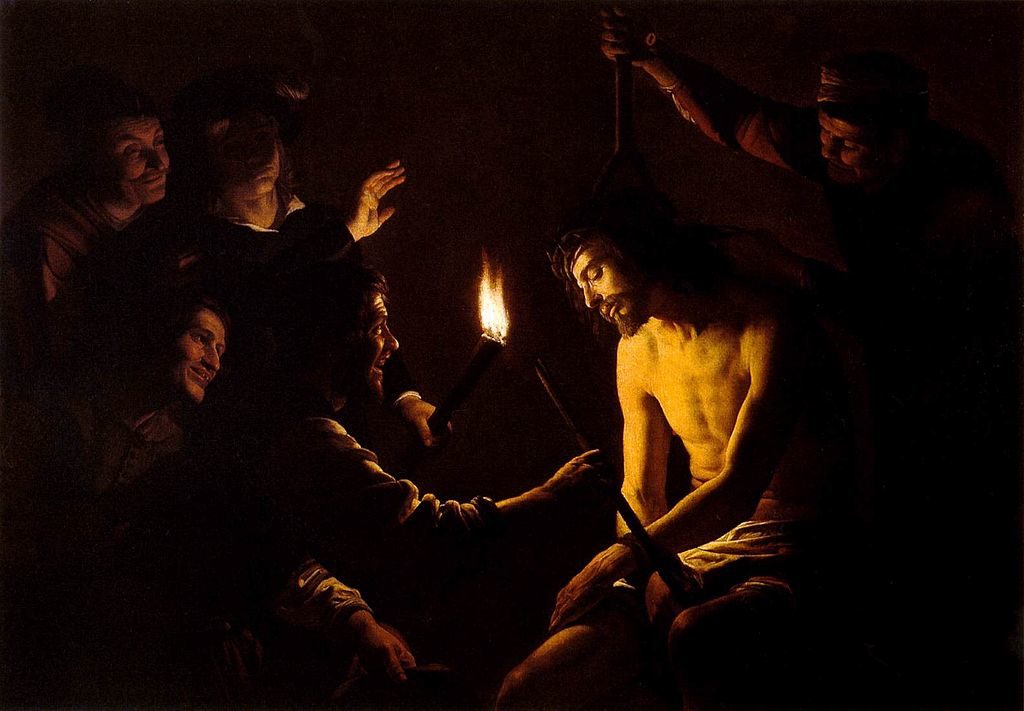

In fact, it is no trivial matter. Relationships are not neutral to us psychologically—perhaps only logically—they are not even a slight influence. Psychologically, relationships can be life or death.

“No more fiendish punishment could be devised, were such a thing physically possible, than that one should be turned loose in society and remain absolutely unnoticed by all the members thereof.”

William James

Even those cold-blooded, rational-types cannot escape the dire need for particular ways of being recognized. In fact, their aloofness itself may only be an attempt to be recognized in a certain way, as an independent. But why is the way we are recognized such a strong motivation when we could survive without being recognized as any more than it takes for emotionless transactions at the supermarket checkout?

The Need to Be Seen

Let’s consider what our first relationships were like. From infancy through childhood we were totally dependent on our parents. If you needed something, you had to get their attention. That was the only route to survival. For them to ignore you would have been practically a death sentence. Imagine how terrifying that would be if you were placed back in that position now. It would be a nightmarish scenario of needing someone to come and bring you food, while every time they leave, you have no reason to trust that they would come back, and there was nothing you could do about it. My mind goes immediately to the times when, as a child, I’ve wandered off in a big store, and after the brief search for my parents ends in vain, I had expected them to have left me at the store. Of course, they never did, but the dependence was a strong motivator for the running around glancing through the aisles.

It would take some time before we learn how we could trust our caregivers. This manifests partly in the well-known attachment styles (i.e., secure, ambivalent, avoidant, disorganized) which have so much to do with our psychological health and relationships in adulthood. Attachment theory has so much to do with how we attempt to gain the recognition of others.

But sometimes for a child not being recognized especially in unknown situations. And sometimes the attention he or she sought was also the cause of some negative outcomes. Like a parent who fed a child but made her feel bad about herself simultaneously. This creates an ambivalence which only comes when something you rely on for survival is also the source of your discomfort.

Growing up, being recognized is still psychologically equivalent to survival. The recognition of others what has kept us alive and now it is mentally tied, by habit, to survival. That is why our embarrassments feel like deaths. That is one person feels like he could die for another. That is why we become depressed when we never receive the recognition that have so greatly desired.

I think that, for many people, our social lives can be greater motivators than our biological lives. There is evidence that survival of the recognition of a person will sometimes eclipse our need for biological survival. Reckless and self-destructive behaviors done for acceptance in a group is evidence of this. For this reason, the rationalist, who denies any social forces acting on him, is denying a universal human phenomenon.

Personality and What We Show Others

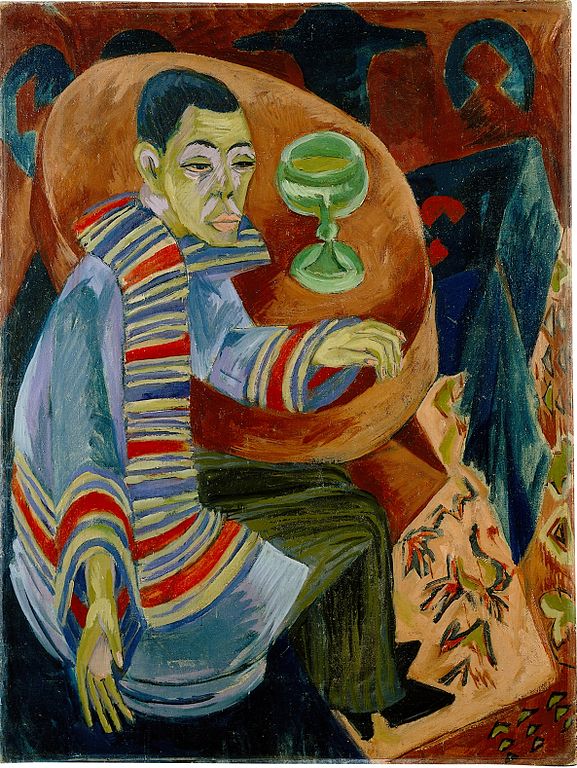

So how does this need for recognition manifest itself in all these various ways, even ways that seem to be aloof and not needing any recognition? There is a single word that we use to describe the strategies of controlling the impressions we give to others about ourselves. That word is personality.

For us reading this, most of our personality is a plaster that has hardened long ago. From the genetic influence to how we have adapted to our environment, we have developed strategies of what ways we are comfortable being recognized. Most of this strategy is unconscious. We do not know the reasons why we have this style of interacting, for the reasons were created long ago, before we even hand language to conceptualize it and write it down. But our personality can be viewed as a strategy for being recognized and surviving childhood passed down to adulthood relationships.

To grasp how our personalities are reliant on the recognition of others we only have to see how our much our personalities vary based on who we are with at the time, whose recognition is central to our present “survival.”

“A man has as many social selves as there are individuals who recognize him.”

William James

James gives the example of “a youth who is demure enough before his parents and teachers, [ but who] swears and swaggers like a pirate among his ‘tough’ young friends.” Or a man can be “tender to his children [but] is stern to the soldiers or prisoners under his command.” We are no strangers to other examples of this while observing others, and even in observing ourselves. Sometimes we feel fake or split because of how we act so differently from one social setting to the next.

Without thinking, we are strategizing and trying to imitate the modes of recognition that we once needed to survive the terrifying situations that we had as infants and children. Whether it was abandonment or drawing in too much attention from others, we had our strategy and somehow still have it today.

Conclusion

But this does not mean that we cannot make conscious changes to our personalities. Personality tests and types tell us our strategies for how we want to be recognized—or not recognized—by others. Introversion, openness, agreeableness all seem to be traits of how you can achieve an image to be recognized by others.

How we attempt to gain the recognition of others is by adjusting our outward appearance. This is what we have done unconsciously for our whole life by virtue of having some personality types. But we can also find the connection between our strategy for our appearance, and the object of desire behind it. What type of recognition do you seek when you act so shyly? Aloof? Aggressive? Needy?

To deny the importance of being recognized by others, denies a useful tool in understanding the ways that we act. We can become aware of when our actions are trying to build a certain relationship or non-relationship.

Ask yourself, when reflecting on past social interactions, what kind of attention you seek. How is that a defensive strategy? Or how is it a cry for help?

And even if you find yourself overly concerned about the opinions of others, do not let this be an excuse to become even more self-conscious. I do not hope to overemphasize the actual importance of other people’s opinion of you. I am just trying to give you a strategy to see the reasons why you obsess over your self-image—why you care so much about that person’s opinion of you. It may come as a solace that your concerns are normal and justified so long as they strengthen relationships. If they hurt you or others, it might be worth digging into what sort of recognition that you seek. It may not be simply love, it could be fear. But it is just as likely to be much more complicated.