“We are fish,” say evolutionary biologists Heather Heying and Bret Weinstein, and no, they have not totally lost it. The point they are making is that the biology of the human body has conserved much of its organization throughout its evolutionary history, and fish are in that history. Single-celled organisms are also in that history, but what, if anything, is conserved those billions of years between the first life and humans today, and how could it possibly relate to cognition? Could there be anything about what it is like for the first organism to “know” that is shared throughout all life? Can we gather up wisdom not by merely thinking of human as an animal, but by going deeper to thinking of us as an organism first?

My argument, inspired by the theories of Varela, Maturana, and their many collaborators, is that yes, if we shed our overly abstract and explicit notions of knowledge, we will reveal patterns of cognition that is at the core of all life. These patterns are always functioning even while we calculate, forecast, abstract our way to ideas of what constitutes knowledge and truth. When the first organism acted to maintain its distinction from the background of chaos, there was cognition, and that cognition is still functioning in every organism since, despite our higher-order thinking that seems to circumvent our basic way of knowing to an abstract form of knowledge.

The modern road to truth tends to be paved with collections of disembodied beliefs because they are what is most conscious, most communicable, especially in explicit form. However, knowing and cognition go far deeper than beliefs, far deeper than language. Those beliefs may be the cobbled decoration of the road, but the biological structure underneath is the mortar that allows us to keep using the road.

Why engage in this exercise of finding the biological roots of cognition? To contemplate the roots of cognition may not necessarily be fruitful; studying cellular respiration does not tell us straightforwardly how breathing ought to be done, but it may clue us into why breathing is done and the very basic requirements that constitute breathing. Likewise, how we understand the roots of cognition will humble the hyperrational mind to its original purpose and its original constraints.

Definition of the Living

If we are going to travel the path of understanding the embodied origin of knowledge and cognition, we may gain some insight from looking at how they were present upon the first emergence of life, and in fact, are tied to life’s definition.

Although we know life when we see it, precisely defining what it means to be living is not as intuitive. Most definitions involve the ability to replicate (or reproduce) and evolve, but according to Varela, Maturana, and Uribe, these features are secondary to the more foundational definitions of life. In their article “Autopoiesis: The Organization of Living Systems” the authors ask how can anything replicate without having a defined identity for which to base its copy?

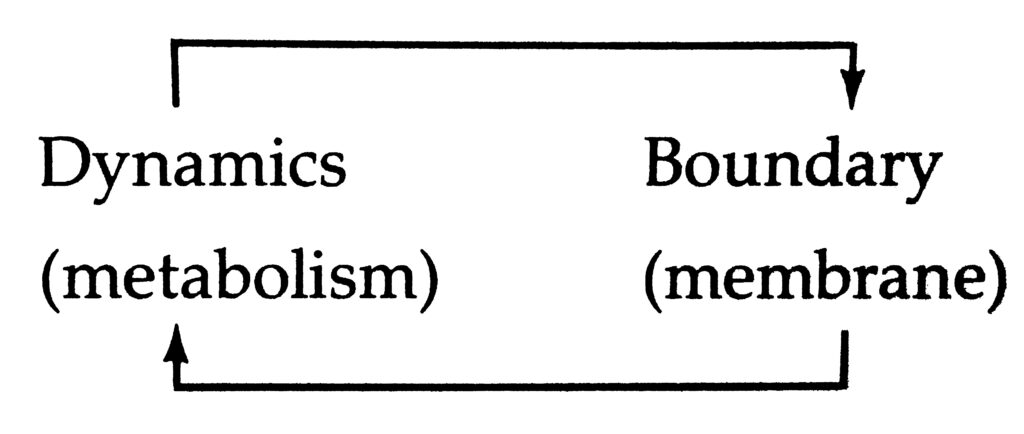

What these authors call the primary defining feature of life is its autopoietic organization: a closed self-creating system. Life is a dynamic system that sets itself apart from its background; it has a boundary (typically a membrane) that sustains an environment for its dynamics (typically called metabolism), which in turn sustains the boundary.

The existence of this biological unity is dependent on its ability to create the internal conditions for which the essential organization of the organism as a whole can continue to exist as relationships between parts despite the constant replacement of those parts. At another time, I will write specifically about the continuous identity through this changing over of parts. For now, this process is just what keeps the system from disintegration, the loss of its organizing wholeness.

“As long as an autopoietic system exists, its organization is invariant; if the network of productions of components which define the organization is disrupted, the unity disintegrates. Thus an autopoietic system has a domain in which it can compensate for perturbations through the realization of its autopoiesis, and in this domain it remains a unity.”

(Valera, Maturana, and Uribe in “Autopoiesis: The Organization of Living Systems”

Once the system is effected outside of its range of tolerable perturbation, which is still determined by the structure of the organism, the organization spirals out of control, it disintegrates, it loses its unity. Like a wheel that loses a spoke, functioning is no longer possible without tearing itself apart.

Dynamic Cognition

Cognition is the process of changing states in to accommodate or manipulate something of the world, in order to maintain autopoietic unity as a response to relevant events in the environment. It can take the form of incorporating resources or by managing the chaotic and destructive forces of the environment.

“A cognitive system is a system whose organization defines a domain of interactions in which it can act with relevance to the maintenance of itself, and the process of cognition is the actual (inductive) acting or behaving in this domain. Living systems are cognitive systems, and living as a process is a process of cognition. This statement is valid for all organisms, with and without a nervous system.”

Maturana and Varela

We typically think of cognition as the processing of stimuli to produce an output. This is a computational metaphor, which can be helpful, but it does not work with a dynamic, autopoietic system. Stimuli are not mere inputs, they are “perturbations” for which the system changes its state, which is determined by its organization. The term “stimulus” implies a universal characteristic of the thing, but perturbation is a relationship between the structure of the thing and the organism.

Even though by this definition one can still imagine this as a computational process, is should be emphasized that it is a dynamic process, constantly changing in order to stay the same. The nature of autopoietic life is like the kingdom of the Queen of Hearts in Alice’s Adventures in Wonderland. “My dear, here we must run as fast as we can, just to stay in place.”

The autopoietic organism must work at speed just to maintain its unity, it does not wait for inputs. That is how a dynamic system works, constant motion, that maintains a unity. Something that has to change in order to maintain itself, like our skin, which is constantly replacing itself just to continue as a “static” barrier.

This is how we must think about cognition. If cognition is a sort of input-output event, like computationalists think, that implies a static state, that does not need embodiment, thus we can invent complex computers, not dynamic minds.

“Dynamic-system explanations focus on the internal and external forces that shape such trajectories as they unfold in time. Inputs are described as perturbations to the system’s intrinsic dynamics, rather than as instructions to be followed, and internal states are described as self-organized compensations triggered by perturbation, rather than as representations of external states of affairs.”

Evan Thompson in Mind in Life

Going back to the wheel metaphor, the wheel is always turning, so one cannot stop it to repair the spoke, one must find dynamic solutions.

Adaptation and Knowledge

“Behaviors [of even single-cell organisms] are implicitly based on presumptions about their environment and are thus cognitive.”

John Mingers in “The Cognitive Theories of Maturana and Varela”

The structure of all autopoietic organisms is relative to the environment, for to be made from it, its existence must have been allowed from by relations present in the environment. The autopoietic unity of a single organism is impossible to maintain for as long as life on earth has, yet organisms still exist, because they replicate. Rather than a physically enclosed living entity, unities exist through an evolutionary lineage. Replication and evolution complicate the notion of identity, by forcing it to change little by little without compromising the autopoietic function.

As the evolutionary process goes on, organisms become adapted to the relevant features and systems of the environment. By this process of gradual change, the organism couples itself to the environment and to other organisms. This coupling to the environment allows the organism to participate in more complex forms of cognition.

The organism gains fitness to its environment. It enhances its “cognition” through natural selection, by becoming more and more coupled to elements of the environment and gaining complexity. We can call this evolved coupling by its cognitive counterpart: “presumptions.” The totality of these presumptions we often call “the wisdom of the species.”

Embodied knowledge, we can say, are the presumptions about the environment that are embodied in the organism’s structure. Their aim is autopoietic unity, and their formation is the evolving interaction between that unity and the environment either through generations or through structural changes of an individual such as the plasticity of the nervous system. Information is not stored in a localized or conscious place, but on many different levels of the organism, dispersed in its dynamic processes.

Knowledge Is Never Complete

The definition of correct knowledge that we must use here is one of optimal navigation of the environment. If something is known, the embodied presumption of a coupled relationship has matched with the outcome of the interaction with the environment, and autopoiesis is maintained. A small bacterium “knows” the gradient of a toxin, insofar as its ability to find paths away from it (chemotaxis) leads it to safety. But knowing is always partial. It does not know what to do if there is no escaping. It does not build up a shell to keep out the toxin. It also may not know how to repair damage from prolonged exposure, and if it does, it may not be able to deal with the adverse effects of that repair process.

Just like we may “know” how to deal with environmental toxins, hence we have a liver and immune system, our knowing is limited by how persistent those toxins are. Our bodies are good enough limiting damage from mild or predictable toxins, but it does not know what do if that detoxing system is overused, eventually leading to system failure via an unknown route.

The judgement of incomplete knowledge is the loss of the unity. It exists at many levels: the lineage, the organism, the system, the part. Evolution is more concerned with the lineage, while individuals are concerned (primarily) with the organism. The mission of autopoiesis is the eternal existence of a self-making entity. It does not take a great imagination to see how it may not ever be complete; there is always the threat of extinction and a chaotic unpredictable future.

purpose, Sin, and Autopoiesis

I began this article with a promise that it would be applicable to our lives, that the origin of biological cognition and knowledge would be something possible to apply. I believe this article is best as a foundation for more questioning, but also has an application on how we see ourselves in our environments. Primarily, the point is to realize that knowledge exists on many levels, and most fundamentally on the biological systems level, which we are alienated from as it is in the unconscious. This sets in motion a story of humanity, which is better told in the Bible than by me.

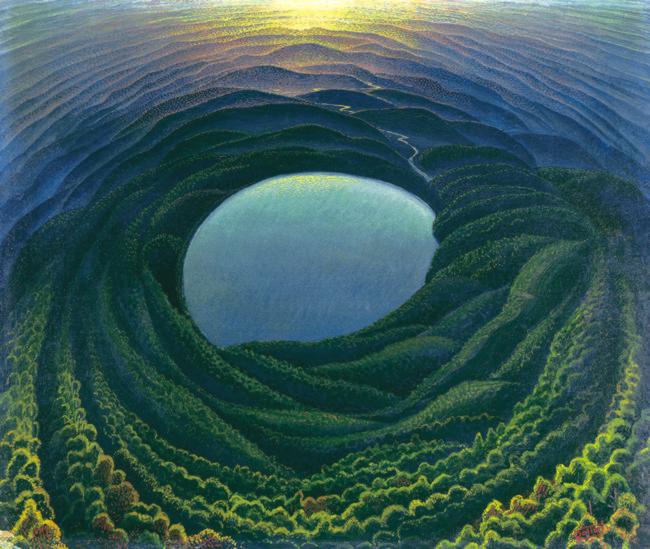

The ideal aim of autopoiesis is a relationship between part, whole, and environment that is dynamic and perfectly matched. The Garden of Eden represents this perfect knowledge. It is where Adam and Eve enjoyed eternal life in the presence of God, who, in this context, signifies the source of complete knowledge (“The fear of the Lord is the beginning of knowledge” – Proverbs 1:7). The garden of Eden would be an environment, not perfect in a complete or static sense, but perfect in the sense of optimal relationship between human as an organism and environment as the perturbance of that organism.

“And God blessed them. And God said to them, “Be fruitful and multiply and fill the earth and subdue it, and have dominion over the fish of the sea and over the birds of the heavens and over every living thing that moves on the earth.” And God said, “Behold, I have given you every plant yielding seed that is on the face of all the earth, and every tree with seed in its fruit…”

Genesis 1:28-31

“The Lord God took the man and put him in the garden of Eden to work it and keep it.”

Genesis 2:15

This, being the way that Paradise is described, is not one of reclining on the beach and being fed grapes; it is a one of a dynamic system. They have dominion over the world, meaning that they can change and tend to things, which perturb them, in a dynamic relationship. It is an image of full embodied knowledge, where one’s presumptions are matched to the outcomes of their relationship to the environment. They are the creative image bearers of God.

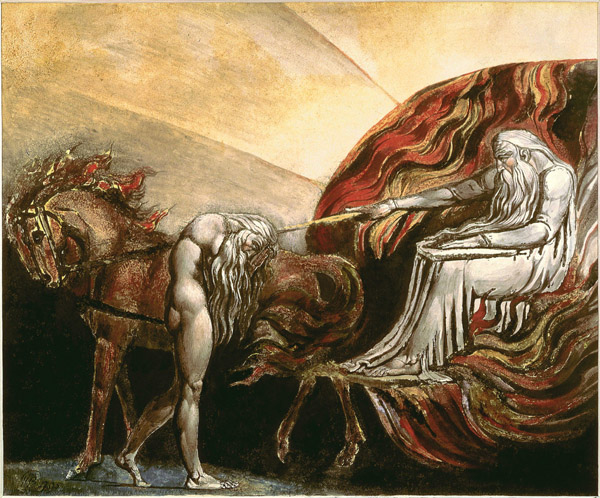

Given that image of perfect autopoietic structural coupling, we can look at the status of human since the Fall from the presence of perfect unconscious knowledge. The threat given for eating the forbidden fruit was death, dissolution brought on by the imperfection of knowledge and relationship with the world. We see the parallel made more explicit in the punishments of the two. They seem almost intentionally proposing the now accepted rules of evolutionary tradeoffs, but to us they are laws of imperfection and incompleteness of knowledge.

To Eve: “I will surely multiply your pain in childbearing; in pain you shall bring forth children.”

Because of the adaptation of the larger brain, childbirth is far more painful and dangerous. This is a prime example of how knowledge, as we defined it here, will always fail to be perfect. For “knowing” one thing, endangers the relationship with another.

To Adam: “Cursed is the ground because of you; in pain you shall eat of it all the days of your life; thorns and thistles it shall bring forth for you; and you shall eat the plants of the field.”

As well as the internal tradeoffs, not our relationship with the world is tenuous, we have no dominion over the chaos, our knowledge cannot go so far as tending the perfect garden.

This was all brought forth by sin, by missing the mark, by incomplete coupling with the environment. We are removed from God’s presence, our access to the ideal wisdom of the species, and thus we have a cosmic mythology for our mortality. And we now understand that paradise is a place of dynamic knowledge, and sin is what gets us further from that.

“For the wages of sin is death, but the free gift of God is eternal life in Christ Jesus our Lord.”

Romans 6:23

Rather than explicit advice, this is an invitation to an orientation to “knowing” the world in an embodied sense, of fitting dynamically to the changes of world, and understanding that “knowing” is an ongoing process that cannot be imitated at one level and without consequence at another. What knowledge is true depends on what level you are referring to, and what is the higher level, and how do you avoid sacrificing the higher for the lower, and how can these levels be aligned and integrated?

Like the bacterium with knowledge of a toxin gradient, we have the biological tools for good-enough genetic survival, but these tools do not know their ends. The bacterium, in escaping the toxin, may lead itself to a dead end where it dries up completely. Likewise, we can be confident that our tools also lead us astray, that the correct instinct at one level is false on another. We are doomed to miss the mark, to overcorrect, to have myopia—that is implicit in the biological foundation of knowledge. But remember what Eden must look like and how do we get closer to that ideal, dynamic state of human beings.

Now that we have an idea of what it might mean that the wages of sin are death. What is eternal life that should not be sacrificed? In the next article, I will attempt to bring these concepts to help define what could be meant by eternal life. This story has another layer. For as we said earlier, there is more than one definition of a unity.