Imagine you are diligently working and you notice a colleague get up from his desk and walk away. His desk is right in front of you, so you are naturally distracted every time he gets up. You work for a little longer and look up and your coworker is back in his seat. He could not have sat without you hearing him, but somehow you did not notice. You think back and now you can remember that, in fact, you did hear him come back, but the event was so quickly ignored since your concentration was fixed on your work. But as you think back, you can imagine the sound you might have heard. Are you remembering the echo of that moment as you heard it, or is it a fabricated noise from which you constructed the memory? Were you conscious of your coworker coming back?

If there was no evidence of your coworker there to force you to explain how he got there, you never would have noticed at all. But just because we cannot recall something doesn’t mean we were not conscious of it either. This is an example of something that happens every day without our realizing it. We don’t typically think much of these things, because it is their nature to be inconspicuous.

Our understanding of our own consciousness lies largely in analyzing the experiences after they happen. We see evidence that a coworker sat down, and so we must have heard it. Even moment by moment we are determining our conscious state by what we can hold attention to, to check if there is evidence of the minds workings and perceiving.

Flights of Consciousness

Attention, as will be discussed, is like slowing down over something in perception. Instead of fast reaction, we hold our sensory organs a little longer fixated on the object of attention. In fact, this may be what consciousness itself is: the slowing down and looking deeper into our worlds as opposed to “looking but not seeing” something. So how often are we “conscious” of something?

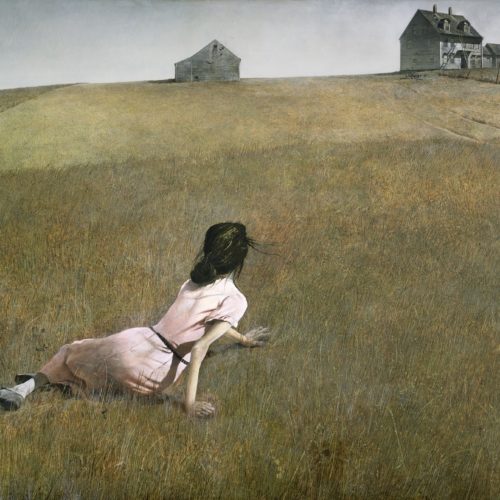

“Like a bird’s life, [consciousness] seems to be an alteration of flights and perchings.”

William James in Psychology: The Briefer Course

This seems to be an apt metaphor to describe the thoughts and moments that we can call conscious. The are segmented into specific moments of being conscious of something. The perchings William James describes as the “substantive” part of thoughts. These are the chunks of conscious that seem to be definable as entities. The flights are more transient, more unconscious and fluid.

To reflect on these flights, William James says, is like catching a snowflake in your warm palm to observe it; it melts away just as it reaches your hand. How do we know what we are conscious of? Is it something we cannot know, but nonetheless are conscious of something?

It is the conclusion of a thought that we know as conscious, the perching only. All that has built up to that was swift and unconscious.

Attention and Present Consciousness – “What” Pathway

It is the conclusions of these flights that are the conscious units we know. So how does a thought or unit of consciousness conclude itself?

Consciousness plays the role of attending to the unpredictable things so that an intelligent decision can be made referencing much more knowledge than by reacting by habit. It helps to conceptualize the situation accurately, even when it is possible to react without a gaging on the exact nature of the situation.

It turns out that some tasks we do not need a conscious experience to accomplish. Such tasks can be performed without conscious experience of a stimulus. There is a patient D.F. that Susan Blackmore uses to exemplify this. D.F. suffers from a visual form of agnosia that makes it impossible to recognize forms and objects. However, she is still able to reach out and interact with them and complete tasks which demonstrate that she does not need to fully recognize an object to interact with it or so that her visuomotor system can “recognize” it.

What this demonstrates is intelligent action without the conscious perception, a conscious experience without its conclusion. D.F. is not conscious of the forms she interacts with, yet she is able to act, in basic ways, like she is. There are two pathways neuroscientists are beginning to study: the “what” and the “where” pathways—although those names are now shown to be oversimplified. D.F. lacks the ability to say “what” something is, which seems to be the unit of consciousness that we experience as the conclusion of an experience.

This makes sense in terms of practicality. We must be able to react quickly to things and interact more directly with the world without the interference of slower and more analytical parts of the brain. The “where” pathway allows this. And “by contrast [to visuomotor processing], object identification can wait. Accuracy rather than speed may be more important when planning future actions and making strategic decisions,” as said by Susan Blackmore.

The “where” pathway of the brain seems to be unconscious, with no memory, and it is tied directly with interacting with the world. The “what” pathway contains sensory experience and immediate memory for making choices between things that require detailed attention or nuanced knowledge of the situation. This allows sensory and perceptual reception to catch up with instinctive or habitual reactions. It is like we have a direct access with the quickly moving world through the visuomotor unconscious, but we can also freeze things as entities by our conscious perception of them.

Our direct interaction with the world is unconscious, but we need further information about these interactions, so we experience them consciously to integrate them into an ongoing learning of a complex world. In other words, moments of consciousness are the finding of the evidence has been just unconscious, in that “where” pathway.

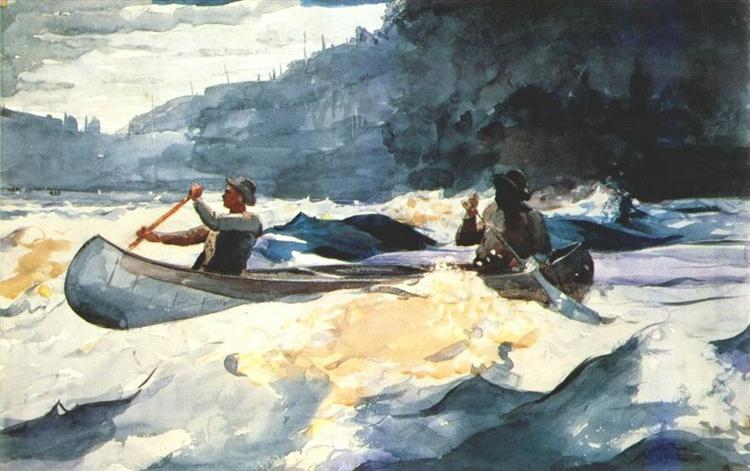

Thoughts in the Fast-Moving Stream

We notice this phenomenon also in quick flashes of images, where the contents are unconscious, but experimental situations show that we still receive enough information to act. However, we do not have enough information to label or remember consciously what it was that we saw. It is conscious experience that allows learning. Often these things are simply covered up by even more salient information that gets the attention to move on before it “looks for evidence” while it’s still there in the mind.

“We cannot deny that an object once attended to will remain in the memory, whilst one inattentively allowed to pass will leave no traces behind.”

William James in The Principles of Psychology Vol. 1

We have a pretty limited attention and time passes quickly, and is gone immediately. This makes it nearly impossible to be exact with what we are conscious of, or to be conscious of everything for longer than a moment. This is especially true when what is conscious is not something that can be sensed in the ordinary way. Our thoughts, for instance, leave no physical traces, only vague mental ones. We can orient ourselves towards something physical to find evidence of our awareness of it, but a thought will have been long gone without anything to be sensed, perhaps only an echo of a few words of it, if it even contained words to begin with.

Even if we put adequate attention to our thoughts in the moment, the only thing left behind is the language that ordered the thoughts, and the feelings which may have accompanied them. What built up to that thought, the flight, is gone. With thoughts, their basic essence is lost, because they are built on a transient substrate. The echo of the words can be remembered but without everything else it isn’t much. I am reminded of the times where I thought something profound out a basic phrase, only to return to it months later thinking, “what did I find so special about that.” The same symbols cannot represent the same thought without being in the same state of mind. This is demonstrated by the age-old wisdom that says we cannot have the same thought twice, as William James also concludes.

This is something, attention and good vocabulary cannot cure but only do justice to. Observing our thoughts and experiences attentively, we will see, is the only way we can get a glimpse of our consciousness. But even so, it will not record it for explicit memory.

“The best plan is to repeat the verbal sentence, if there was one … but for inarticulate thoughts there is not even this resource, and … the mass of our thinking vanishes forever, beyond hope of recovery.”

William James in The Principles of Psychology Vol. 1

This is where journaling can be a great tool. To record one’s thoughts and continue to hold attention on those moments as to give it a full description can be such a therapeutic exercise in understanding one’s conscious experiences.

Another Angle on Mindfulness

To think clearly means to hold attention to the thoughts that normally will pass quite quickly without us gathering the “what” of their essence. An academic, like William James, will have benefited from speaking his thoughts aloud so that the logical structure of thoughts can be remembered. A writer of a journal may also want to write down her thoughts as they come, in great detail, so that part of their evidence can continue to exist and build a meaningful personal history.

But even using the tool of language and symbols is limited in how much information can be held to up conscious awareness. While we think we retain the whole of our experience in language, we soon lose the fullness of experience with its essential context and all. To fully embrace a present consciousness we need something that observes the evidence as it comes. For that we need a languageless technique to capture the “whatness” of our perceptions. To get as close to a full consciousness as possible has been created in the tradition of mindfulness.

Mindfulness is a practice of slowing down and paying attention to the things that normally do not get attention, that can be thoughts, in meditation, or banal activities in some mindfulness practices. These things normally are received but ignored by attention moving onto something else.

Instead of looking back for evidence, mindfulness accepts that evidence is always coming in. This is to be fully present. This is opposed to an unintegrated way of being of continually looking back on the evidence of experience (my coworker must have sat back down), or using reason to find the implication that you had an experience. These are not full experiences, where the flights line up with the perchings. The conclusions of these thoughts are removed from the whole context in which they were thought. Mindfulness is to allow the conclusions to match the context in which the unconscious subjectivity directs our consciousness.

Mindfulness appreciates that we are not meant to keep things perfectly in memory and that we rarely have focused attention to retain perfect memory of experiences. But mindfulness is not a practice in creating a better memory for unimportant things. It is serves as a way to slow the pace of the mind, and see the evidence of perceptions as they occur to the more automatic parts of the brain.