Some things seem to have an intention. They move according to what is best for themselves and with purpose. They seem to have a mind. And some things don’t; they merely are. When we think about the actions of other humans we often consider them to be done with an intention. They were not merely a reactive substance, but a thinking and desiring entity. We assume that we intuitively know that people have intention and inanimate objects do not, but the line is not so clear.

A Belief in Nonliving Intention

Is there really a definite line between the living and nonliving when it comes to the intention that we attribute to behavior in the world? Even intellectually we cannot see the obvious difference if we take seriously the behaviorists’ theory that we are mere machines of stimuli and responses. But in the way we act and feel, we hardly discriminate between what is intentional and what is inanimate. A computer which doesn’t cooperate or crashes will enrage us as if we were beholding a devious trickster who is intentionally ruining our day.

The system of beliefs in other thinking entities is something psychologists and philosophers call theory of mind. For most of us this comes naturally. In fact, we tend to naturally overgeneralize the objects which can have intention. We think the tree has roots because it is trying to get water from the ground. We anthropomorphize the tree as if it were more than a mere biological system of responses.

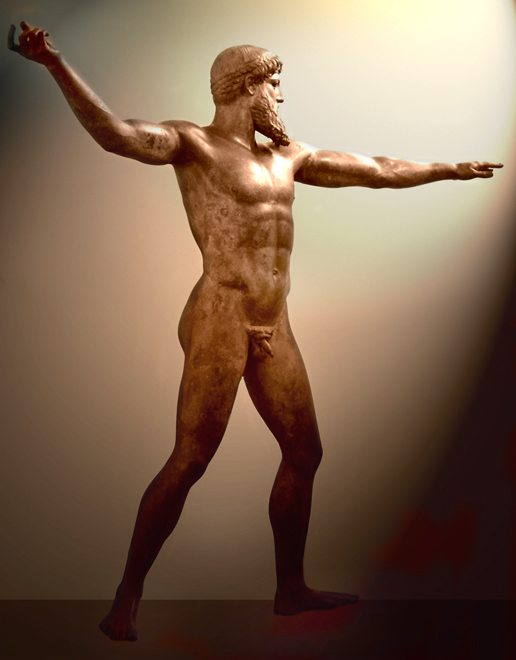

Take for example, the ancient Greeks who had gods—anthropomorphizations of natural phenomenon such as storms, the sea, and the sky. Having gods allowed them to talk about the “intention” of the cosmic, uncontrollable, sometimes life-giving, sometimes destructive forces. In order for us to believe in an ordered world where we have reasonable control, we come to believe these things that we consider as fate happened for a reason. For many of us, there seems to be a natural goodness or evil in the world and some entity is giving it that quality. This is the theory of mind of guardians.

It is those things which seem important to our survival or well-being which we most often project intentions on. If an important thing remains out of our control, something with godlike power, we feel no choice but to give it an intention, something that can give our actions meaning if inevitably the world turns against us. We give the sky a mind when we pray for the storm to stop. We can put ourselves on Nature’s good side, so to speak.

But our attitude towards the uncontrollable varies, for it was learned in the very beginning of life.

Developing Theory of Mind

When we think of theory of mind, we think of knowing what another person is thinking, but it takes longer to develop this empathy and an understanding of what might be going on in the mind of another. It is even earlier in our lives when we figure out that there is a mind—and that there is a bond between minds.

Although and infant cannot know the content of another mind, he or she can feel the security of that person’s intention. The infant intuits a consistency in the person, to provide for us, is something to do with their bond with us. A child cannot think in these terms but feels the bond, in his or her bones. It is a necessary trust. We come to naturally believe that others have intention because we would have been abandoned if they had not, if they had no love.

The child goes the route that a person helpless to the world goes: to prayer, to hope, to a believe in a divine guardian. The child has no choice but to believe in another mind. That belief is what secures the child and keeps anxiety of helplessness at bay. That belief of another desiring being is what gives the child a reasonable believe that that being can desire him or herself. The child thinks, “mom will come back, because she wants to take care of me.”

An implicit bond forms. The parent is the object of the infant’s desire, and the infant is the object of the parent’s desire. The situation is best put in the words of David Winnicott: “that there is no such thing as a baby—only a baby-with-mother.” The child cannot think of himself yet without the mind of its “mother” to fill the role of protection.

This belief is base, unconscious, and tells the child that the world is ordered and worth fully living in.

Indifference

How are we conditioned to have something not have a mind? When we have an unconscious belief in the agency of the world, some things seem to exist outside of that world, things which we cannot comfort ourselves into knowing have meaning. These things, we find, are indifferent to us, yet we depend on them.

It is an indifference to your needs that leaves things out of the possibility of mindhood. The tragedy of having an indifferent parent creates an anxiety of helplessness. The mind of something which shows its indifference to your needs, is wiped away. It is an anxiety-provoking belief. Nothing wants to tend to your needs in an indifferent world, you must control it yourself—if you can.

The weather to a farmer, being totally untamable and life-giving and death-dealing, will feel mystical, like a goddess who demands respect. For there is otherwise no hope of consistent growing.

But we learn, in studying weather patterns, the indifference of nature. We learn that weather is not here for our survival, but that we happen to be in it, surviving. There is no sense praying for rain, and this brings anxiety for those who must rely on it. Honoring and respecting nature will not work if it is indifferent, so manipulating it is our solution. The anxiety forces us into controlling as much as we can, taking piece by piece of the uncontrollable and making it another variable adjust. It is an impossible task, but the controlling keeps us from anxiety.

Ambivalence

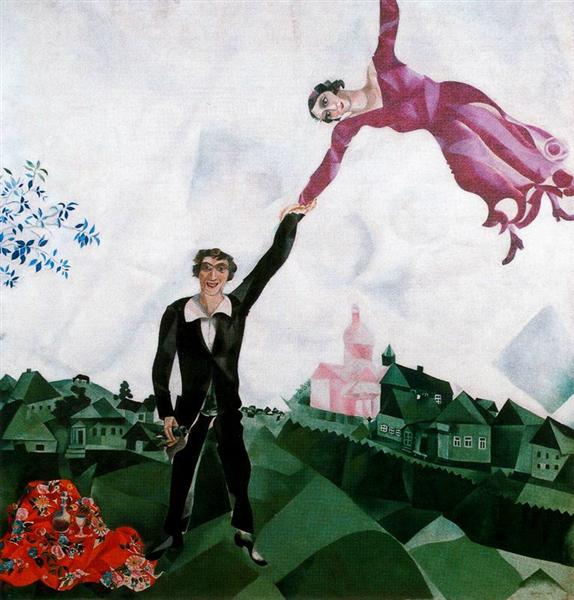

Our reliance on others also causes an ambivalence to that other. It is degrading to admit reliance on someone especially when you are trying to declare your independence and expand yourself outside of the sphere of your guardian’s sights. You hate and need this person at the same time.

We do not want the love of someone that controls us, yet we still somehow need it, psychologically at the very least. Parents to a teenager are the objects of this ambivalence. They are in financial and legal and practical control over the teen, but the teen is seeking his or her autonomy. They want to be free, but know that they, at the moment, cannot be.

A tyrannical ruler will be the same. The people who are oppressed will hate the ruler, but also have to cope with the reality that they are reliant on the ruler who has the power to destroy them.

The solution for the person who is ambivalent will be to negate the mind of the other. To not believe in that secure bond, and to ensure that they can be totally free of the relationship, because it is psychologically oppressive. To avoid the anxiety of this ambivalence the person will pretend that they do not need the other, but at the same time still being reliant on the other. It is like being served a horrid meal on a road trip because there are no other options. You take the food with defeat.

A Respectful Conclusion

Ambivalence towards the parent and indifference of the parent are ways of negating the love of a parent-child dyad and all the other relationships that might symbolically represent that relationship. We deny that there are other minds, despite our deep conditioning of the idea that things we rely on have minds which have opinions about us and love us and treat us according to that love.

Do I advocate for a sort of panpsychism? Should we believe that everything has consciousness? I would not say that we should rationally explain things as having intention. To claim, after a natural disaster that God was punishing these people for such-and-such would be an irresponsible way of putting intention in the world.

But it seems that our problems come from where we do not see intention, where things are meaningless. People can be oppressed when we remove their intention, treat as objects to be controlled or isolated from the community. To feel a bond of inter-reliance between minds (animate or inanimate) with others is a natural trust in something deeply human. In this sense we are choosing to love over the fear of indifference and ambivalence.

Nature may literally be indifferent, but acting as if it has a mind, will help us respect it, and look for ways of respecting it which actually has a positive effect on how we can deal with the problems we face at the mercy of nature. The alternative is manipulation of the world and making it into equipment.

Or if you see the world with ambivalence, you will see it as something to escape, yet it’s ties tighten every effort you make. You know you are reliant on the world, we all are. And being free of it means losing what you need. Perhaps accepting the reliance without feeling defeat is the first step to resolve ambivalence. By leaning into the anxiety, we come out on the other side a little more secure in the world.

Acceptance of a somewhat mystical sense of trust in the other is necessary to live without defending against the anxiety and to honor and love the minds of the world.