To understand consciousness means to develop an idea of how meaning comes to be. To grasp meaning at the early stages of biological life, we have to establish an essential aim of biological organisms. Cognition is an embodied coincidence between expectation and reality that leads towards the teleological end for the organism. To judge that cognitive process means you must understand if the result aligned with the expectation of the organism. The last two articles have worked on what those ends are, but here I offer a challenge to those to present the problem which consciousness will eventually attempt to solve.

We’ve established that organisms aim for self-organization (autopoiesis), and therefore if adapted to their environment, they have “expectations” of how to meet that goal. Additionally, because the organism’s existence is predicated on genetic replication, its aims at genetic replication and identity have been embedded in its self-organizing machinery. So, the processes of self-organization must be in service to the survival of genetic identity. However, more follows this aim, for no organism lives today by its insistence on producing exact copies of itself. This article will discuss a further aim of biological systems, and propose the problem we come to by looking at cognition from the material perspective.

Identity or Adaptation

We began with knowledge being best defined in its conservative aim: knowledge is what keeps the organism continuing its self-organizing processes. Knowledge is also what the organism has that brings it to replicate its genetic identity. Its expectations and interaction with the world are judged by the result of its intergenerational existence. Whether stressors of the environment are toxins, predators, or the passing of time, the natural definition of accurate embodied knowledge appears in the preservation of identity as it contacts that chaotic world, as an organism or a lineage.

The principle of knowledge as conservation is also true in the realm of ideas. If you have a concept of something that is unaffected by contact with reality, then we would consider that knowledge accurate. If I interact with the world without having to change my beliefs, that yields favor on those beliefs. Like the embodied knowledge that preserves the body, the conceptual knowledge preserves the concept.

This principle is also true intergenerationally. Each generation is a preservation of what was accurately embodied knowledge of the previous generation. Thus, embodied knowledge seems to be both what keeps the organism organized and what get the organism to replicate identity before its time comes to an end.

However, any evolutionary biologist knows that conservation of genes cannot be the whole aim of organisms. We run into the same problem we did when we said an organism is made to perpetuate its own autopoiesis: namely that it is a dead-end strategy without genetic survival. Likewise, perfect genetic fidelity between generations will result in an end to the lineage.

The primary characteristic of life today is how adapted organisms to their environment. That could not be the case if organisms were focused on faithful replication and conservation of identity. It takes variability in organisms to adapt to an environment. So, if embodied knowledge is to be something that preserves, how do we account for the aim of organisms to adapt and change?

Changing to Remain the Same

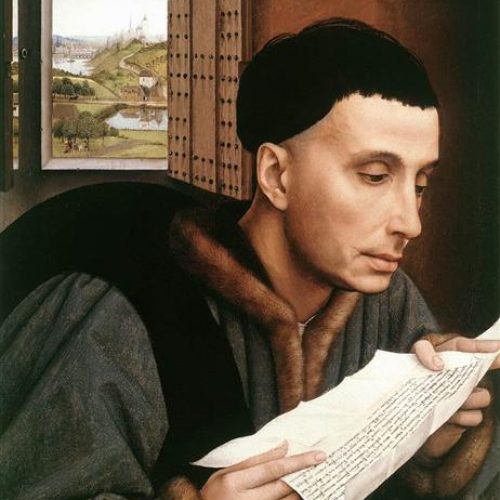

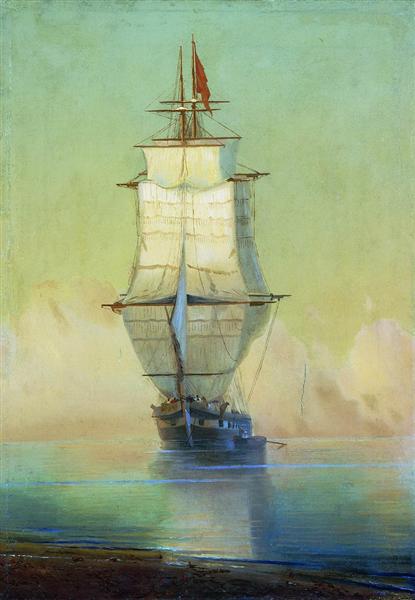

The thought experiment of the ship of Theseus is a popular way of understanding how identity is preserved while the parts are changing. If you were to take a ship apart piece by piece, replacing each board so that the ship is never completely disassembled, most people would say that the ship has the same identity even after each part is replaced. Likewise, we share the same identity as the human we were ten years ago even after each molecule is replaced during that time.

However, if the ship were adaptive to a changing environment like biological lineage, this would complicate the story. Imagine the climate changed in such a way that, in order for the ship to continue its useful existence, it had to be slowly replaced by parts that would help deal with the challenges of the new environment. Through time, the ship needed to be reinforced against ice, wind, or new enemy weaponry. The trajectory of the ship has two routes. If the builders decided maintaining identity was more important than sacrificing some identity for adaptation, the ship would stay the same and likely perish as the environment changed around it. If the builders took the adaptive approach the ship would survive the environment, but may not resemble its old structure and lose some of its efficiency that it had before it was weighted down with adaptations.

In this example, the latter strategy turned out to be the better for preserving identity. It was not a totally radical strategy, but an incremental one. That is because the original design of the ship was efficient and still relevant for its main purposes (to float, to move, to be steered, etc.). The “motivation” to preserve identity is not for its own sake but for the sake of preserving the most efficient strategy for the essential relationship with the environment. And organism will still preserve its main metabolic processes while its peripheral mechanisms change, because those processes are still essential to the organism.

Adaptation and the Problem of Unpredictable Error

For evolving creatures, the expectation of these conditions is not predicted by the conscious intelligence of ship builders, but by two things, by replicating what worked in the past (determined by success self-organizing and replicating) or by predicting the unpredictable by inserting randomness into the generations of a species. The “aim” of preserving genetic identity is equivalent to the prediction that what worked in the past will continue working. Imagine now two colonies of bacteria:

One colony is aimed at preserving its identity with fidelity. It is justified in doing this because many generations of the colony have done so successfully and have proliferated with efficiency. In terms of efficient conserving of identity and relationship with its environment, this colony is doing great. However, the unpredictable occurs: a scientist is housing the colony in an experiment and pours acid onto their petri dish, destroying the whole of the colony. Their identity was completely lost, their collective embodied knowledge was not predictive of such cataclysms, and their “motivation” for identity preservation was proven tragic.

Another colony of bacteria aimed less at preserving their particular identity, but rather produced broad variations in their genetic code. The consequence is that they never fully mastered their changing environment, and their population did not grow drastically. However, that scientist poured the same acid over them, and a few survived enough to repopulate the colony. That colony, we can say in this case, had some collective embodied knowledge or species-level knowledge which was better than the first, even though it has a looser and less efficient relationship with the environment.

The problem with this definition of knowledge for our application is that it was judged by a matter of luck and passing of time. For most of the time, we would have said the first colony was the best, then unexpectedly, it wasn’t. There was no way for the organism to predict the outcome. Had no cataclysm occurred the first would have been judged higher. But this is the strategy of biology, to preserve reliable efficiency and insert (partly random) inefficiencies to buffer the catastrophic events.

Conclusion about Necessary Maladaptation

What does this say about our attempts to define cognition? Before it was once about achieving an efficient and adapted relationship with the environment and being able to lodge one’s genetic identity into the future. Both of those motivations seem to be threatened by the method that organisms adapt to their environment, because that means the organisms are inefficient and genetic survival depends on being malleable.

Evolution is a process that tests out “hypotheses” of imperfect variations of a species. Perfect does not exist for evolution, because it always assumes (correctly) the potential for drastic change and need for adaptation. Even if it were to somehow create a perfectly adapted species, it would still throw in imperfections so that it can survive the unpredictable. In reality, there is both stability of environments and there are unpredictable changes, sudden or gradual, that affect how the organism functions in the environment (is embodied cognition). Organisms are balanced between efficiently mimicking the past, and “resiliently” incorporating error or change. According to the laws of nature, one must walk the edge of a razor between preservation of what works and taking random chances at incorporating randomness that may prove beneficial.

Unfortunately, this means that any individual organism is doomed for imperfection, for being slightly alienate from the environment it lives in. Even when the environment is one’s “natural” environment, things are not meant to be perfect. Biology knows its better to have an imperfect match to an environment if it allows for adapting to novelty.

This should remind us of the exile from Garden of Eden. Where the two humans were designed in perfection with their environment. They could do as they always had, obey the voice of God, and have perfect autopoietic knowledge (eternal life), but they listened to the snake (representation of unpredictable chaos), incorporated the forbidden fruit (assimilating the potential for error), their eyes opened (representing the vision to see potential error), and they were exiled from the Garden (autopoietically perfect relationship to reality). Here, I am not treating this story like a historical past, but as a representation of how we, as humans, intuit that we are not meant for this world, that we are meant to have an Eden-like relationship with the world, but it was lost in the necessity of biological evolution.

The problem is where do we go from here? It appears that we are stuck between efficiency/identity that cannot adapt to the unknown and inefficiency/diversity that is not aimed at autopoietic needs. The measure of cognition is obscured by the needs of biological evolution. The next article will address how, even though, there is a beauty in this problem, we cannot stop there, the world without judgement is meaningless and chaotic. The solution needs to get beyond the trade-offs nature provides.