A certain level of understanding of the world and ourselves is basically a privilege that only human beings can accomplish. We have intuitive “understanding” which signals that we have had a lot of experience in certain situations and how to deal with them, but the conscious understanding is quite different. Intuition and behavior, no matter how seemingly intelligent and useful, are not understanding. We need to consciously perceive so that we can understand. We need to make the imperceptible, what only intuition could grasp, into something we can perceive. To solve this problem, we have learned to manipulate things in the world to turn elements of reality from invisible or intuitive to perceptible. In another article, I have called these tools of inquiry.

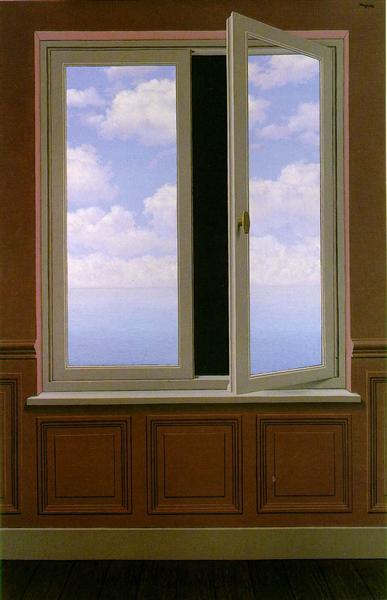

What we must know is that these tools are not clear windows to a reality. They contain predictable limitations, of which we must become aware so that we draw accurate assumptions of reality, and then ultimately to improve the tools. This is the basis for improving not only scientific understanding, but also philosophy and self-understanding—for we use tools for access to these realities as well.

Review of the Tools

What do I mean by “tools of inquiry?” Another article details the theory behind what they are and gives in depth examples. But here I will briefly describe the common features of these tools.

Primarily, these are devices that we use to reveal the world to our senses in a clear and discrete way. The simplest example may be the microscope. A microscope changes light in a way in which we can see microbes that were hitherto invisible. We may have suspected the microbes, but without seeing them, they have not been brought to conscious understanding. Some reality has been revealed in that experience.

Other tools can do this same thing. Recording events with writing allows our intuitive sense of memory to be extended into longer periods of time with specific recorded information. Mathematics is a tool for understanding real proportions of our three-dimensional world. Defined language is a tool in which relationships between ideas can be developed, as in thought experiments. Finally, art combines many of these tools to let the human psyche bubble up to material awareness.

If we think of these tools as such, we can begin to see the limits of them, and therefore the limits of our knowledge and what we must take on faith. Whenever we transfer information from imperceptible to perceptible and intelligible, we lose and distort some information in the process. Improvements of the microscope, for instance, directly improve the reality being converted into visual information, but they may always have their limits. These limits, of course, can be pushed, but not without understanding them first.

Limits of Our Tools

All of these tools I have described have their own limitations which can become problematic when we expect them to reveal an unaltered reality. Here I will discuss the limitations specific to the five types of tools.

Extending and Transforming the Senses: Instruments and Tests

Consider the microscope again: it is the most direct example of a tool for understanding reality. It simply reveals the smaller world, right? However, the microscope still requires some understanding of what it may alter in converting the invisible to visible. For instance, some microbes may only be visible if a dye is used. For certain features of the cells to be visible, the dye must bind to specific the parts of the cell that we want to see, and not bind to the others. The microscope cannot help us with what is still too thin to see without the assistance of dye. Even a tool that seems to simply enlarge the picture of the world cannot simply do that without having some sort of limitation or distortion which we must understand in order to interpret the information we have and how it reflects reality.

A litmus test is a similar way of converting the imperceptible into an unambiguous measure: acid or base. Although it does not pretend to say more, the useful tool meets its limitation in that it can only tell us a single minute fact about a chemical: its pH. The same can be said for all other chemical tests.

External Memory: Diagrams, Charts, and Records

Our perception of time is never very exact. Especially over a long period of time, we have to rely on a biased intuition if we cannot keep records. This allows us to let information persist through time until it can be compiled together to show a pattern that we could normally only intuit. But as with all these tools, recording information is fraught with limitations and potential deceptions.

When we record something, say with a camera or on tape, we think we get the whole, objective event. We are literally taking the past and preserving it into the future. However, every record is edited in some way. Simply where the recording starts and where it ends is subject to some limitation in objectivity. In the case of other recording devices, they only say more singular measurable facts. Whatever is not recorded (i.e., out of frame) may not be any less important than what is in frame. Every record leaves a narrower picture of what the real past had been.

Similarly, with writing down in a journal, we externalize and preserve our experience, but with the words we have chosen, we have done so in a very limited way. When we look back on the journal, with only the words and what is left of the memory, it may have little of the same meaning that it had when we wrote it.

Our inability to bring total reality back from the past means that we must become like archeologists interpreting what records and evidence has left behind. Interpretation of records requires skepticism and the understanding that something must be missing.

This shows the necessity of detailed records. The more we have to guess, the more inaccurate and biased our conclusions may be. Yet, perfect records will never be realized, and much of the past is already lost.

Exactness of Measure and Statistics

Math is set up to start with assumptions like what an isosceles triangle is, and from those assumptions, math draws exact conclusions. Of course, perfect geometrical shapes do not exist in the actual world, but the theoretical applications of math still apply, just less perfectly to the world. The obvious limitation here is that one needs to mathematize very specific things which are difficult to put on a single scale. “Happiness” is manifested in many different ways, and I am not convinced that there is a single way of enumerating it.

Statistics is a branch of math that means to have direct application in the complex world. Statistics seek to find patterns in the world that can be converted into numbers (and sometimes names). In addition to the limitations involved in converting reality to numbers, statistics suffers from the impossible fact of randomness and predictability. For that reason, conclusions of statistics are probabilistic rather than definitive. We often forget what the statistics mean when we quickly interpret a statistic.

For anyone who has taken a statistics class, I do not need to say much about how complicated statistics can be, and how much effort is put into drawing conclusions to fit the evidence. I do not need to say how careful statisticians are compared to the media in drawing conclusions about the statistics.

But this does not mean that we cannot draw conclusions from statistics, however we may be better to call them “provisional assumptions.” The limitations of the tools of mathematics and statistics are well studied and sometimes overcome. What we must keep in mind is exactly what the numbers are saying, which is often a very qualified conclusion, often calling for more information. And we must keep in mind the many other potential variables that may have effects on the conclusion.

Language and Concept Definition

Defined language is similar to mathematics in that they are symbols which can define an ideal. But language is more complex. Words have changing definitions, multiple meanings, and unintended connotations and usage. But its limitations are much the same. Language can never represent the full reality no matter how precise of a language we create. The project of science and philosophy is to create the vocabulary most representative of reality. Ultimately, we will never reach a perfect language because of language’s inability to reflect the unstable complexity of reality.

Language of course did not begin as a method for defining reality, nor does it have the purpose of that. Language is originally emotional and social, above all else. But we have learned to create definitive vocabulary which we create to help understand concepts (perceived patterns in reality). Of course, the emotional and social creeps in as we do this, but the limitations are also more fundamental.

Rather than try to add to our experience of reality, defined language attempts to qualify and draw apart terms. Definition does not create ideas, but it makes them separate in order to communicate fully and comprehend. Words, before definition were loose and had no significance beyond how they were used. When we defined them, we put a border around them and made them exact so that in the world of ideas we can perfectly understand them. However, that border is not reflective of reality. That is why we need understanding in addition to good language to comprehend reality.

Art and Free Expression

As we go further down the list, as we discover the tools that seek more meaningful and ambitious conclusions about reality (particularly our reality). Rather than simply revealing the existence of microbes, these tools reveal much vaguer and abstracts parts of reality. Here, the limitations of our tools become more apparent, but the reward for drawing conclusions is even greater and more tempting.

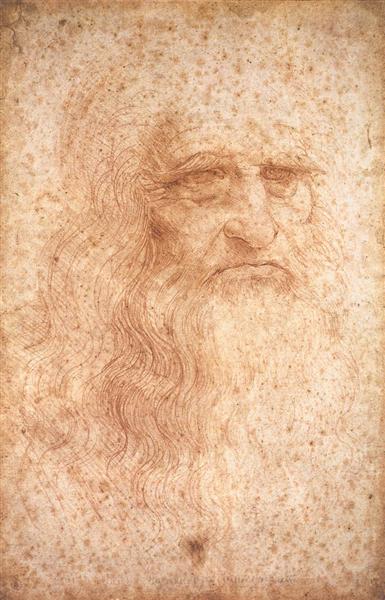

Art, of course, can be the combination of all these tools, and can suffer from much of the same limitations. We convert an emotion to a visual or musical experience, to become more aware of it, but ultimately the conversion it not total. We express in the moment, recording a moment of existence in a single artistic action, causing our re-experience of the artwork to be missing something of the experience which provoked the work. Mathematics, proportion, and conceptualization are relevant in many expressions which suffers from the same limitation of aiming at a perfect ideal and missing it in reality. Whatever the artist aims at has to be a finite version of the infinite reality they express, thus the name “fine” arts.

What becomes most apparent when we include art within these tools is that they take practice to allow them to reveal the reality that we are hoping to see. It may also be the artist that knows how to deal with the limitations of his or her medium. You do not often see the artist satisfied by revealing truth as you might see an uninitiated scientist or statistician do that. The best of these artists, thinkers, and scientists know that their work is never a complete representation of reality.

“Art is never finished, only abandoned.”

Leonardo da Vinci

We shall see how we can improve our attitude towards these tools, by understanding their incompleteness and taking the artist’s approach to the conclusions.

Faith and Humility: Our Relationships to Tools

There seems to be two main ways our tools of inquiry deceive us. The most obvious is that we lose information when we convert it to something perceptible. This can mean getting partial information which seems like a reality, but it is missing the whole picture. We can also gain extraneous information; artifacts show up in x-rays that may confuse a novice eye. These are deception which come naturally out of some tools if we do not have understanding of them and their subject.

If we are the inquirer, by allowing instruments like, art, definitions, statistics, we must know what those limitations of our discoveries are. I believe it is the responsibility of the inquirer to know how their domain is limited in its understanding. Particularly with the mysteries of ancient civilization and evolution, conclusions are almost always speculative. But often it is the inquirers who understand the tools and have the humility to say that there still remains many unknowns. That is the nature of the inquiring into the truth.

We often hope, far too much, that we have uncovered a reality using our tools of inquiry. We look far too much towards the conclusions than the process and interpretations. Conclusions are important to resolves conflict, but the seeking truth is halted when we make conclusions despite the limitations of our tools of inquiry.

“Man has, as it were, become a kind of prosthetic God. When he puts on all his auxiliary organs he is truly magnificent; but those organs have not grown on to him and they still give him much trouble at times.”

Sigmund Freud

We will never have adequate tools (or prosthetics) to see reality so directly—as God would. But we can now understand how to interpret the information that we get from our ingenuity. They obviously reflect some parts of reality, but at best we can only call what they discover “provisional assumptions.”