In these initial articles, I am attempting to point towards the mystery of what lies beyond our physical and perceptible reality according to the mysteries at the depth of our experience and our encounter with the world. This is meant to be a launching point from which we can understand cognition in both its material and spiritual significance. In the last article, I argued that, by taking a phenomenological approach to psychology seriously, we have not only a justification for believing in a spiritual reality, but our very assumption of morality is founded on it. It is in our seeing others as having minds like our own, making them participators in the creation of meaning, that we can conceive of a meaningful reality that exists beyond mere material. Rather than understanding knowledge solely as a grasping of material facts, we understand knowledge in its biblical sense of loving relationship in which we both give and receive the gift of subjective meaning-making.

However, someone could see this pervasiveness of spirituality and meaning and come to a belief just as extreme as the materialism we rejected in the last article. If we accept that that all we can know comes through a filter of meaningful interpretation, it is a natural conclusion to draw that meaning is not only the truest reality, but perhaps the only one. This position I will name here as “idealism,” and I will elaborate on its consequences, why it is wrong, and invite you to a unique way of seeing the world that accounts for the material world but does not result in materialism.

What Is Idealism?

Before we understand idealism, we need to describe what ideals themselves are. In the Platonic sense, they are the universal patterns in the world which govern its beauty and meaning, and we imitate these patterns in our behaviors. Jordan Peterson describes ideals motivationally in Maps of Meaning as implicit desired outcomes, which are often contrasted with the inadequate present. Every intended human action has implicit aim, and action is presumed to bring someone closer to that aim.

This is not unlike how we described faith in meaning, not as a state of what things are like, but what they ought to be. To experience meaning, one must have an ideal to order one’s actions around, and to trust in that ideal is not based on physical evidence but the necessity of approaching the world in faith. Faith, meaning, and ideals, are the propellant for intended human action and is not something that can be measured and controlled before enacting; we must always be in a state of trust that there is something more to move forward in life.

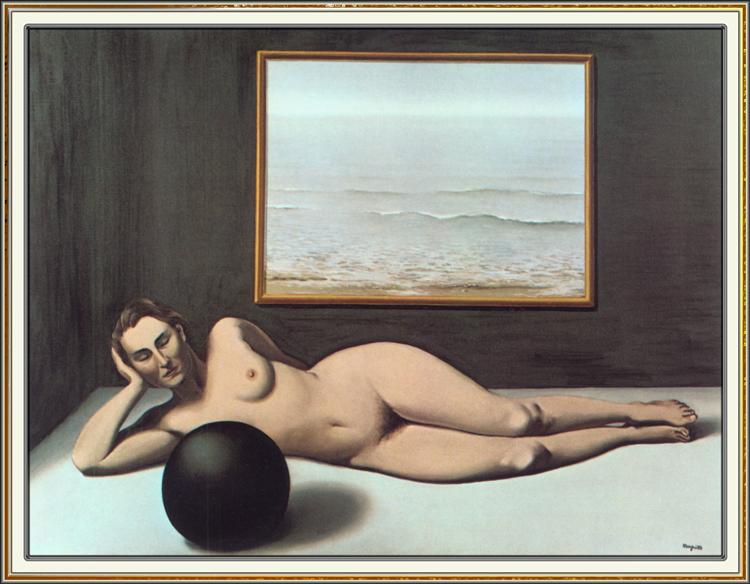

However, as we abstract on these ideal aims, we come to what I would call “idealism” which takes this reality of motivation and faith and absolutizes it. Our journey from the present to ideal future shifts drastically to the preoccupation with the ideal. In our minds the ideal becomes ever more purified of the limitations of embodied reality and it begins to promise eternal satisfaction without the body. We then make our present state and our bodily limitations the enemy of meaning.

Take, for example, the idea of a perfect circle. We have the mathematical formulas and definition of what a perfect circle is and how it behaves, but we have never seen one either in nature nor computer generated. All iterations of circles in the world are technically imperfect. But however roughly drawn a circle is, it still behaves approximately according to the mathematical laws of an ideal circle; it points to a perfect reality. The ideal circle is both more real and unreal simultaneously. But it would be folly to see all circles as deceptive or deficient because they are not perfect. If we could not see all the imperfect iterations of a circle, we could not comprehend or understand a perfect circle. By destroying the imperfect circles, we lose contact with the perfect one.

The same is the case of our motivational ideals, where they are never exactly actualized in the world, but they are governing us nonetheless. It is ideals which bring order to that which is always coming up just short of perfection. Like a perfect circle is never drawn, we will never fully be contented in the satisfaction of an ideal. Each attempt, each taste of perfection, rather than satisfies us, causes us to pursue more aggressively. Each time we are satisfied for a moment, a more perfect satisfaction seems to exist in the future. It is in this mode of being that drives us forward in life, but we are also liable to become enslaved by ideals at the expense of the very potential for pursuit, our embodied present.

Illustration of Idealism

To illustrate the appeal of taking seriously the total primacy of meaning, I will use an excellent image given by Varela and Maturana in their book The Tree of Knowledge. They imagined a submarine operator that had no knowledge whatsoever of the outside world. Only through the instruments and sensors on the vessel can he understand what he is to do, which levers to pull, which directions to steer. In this way, the operator, knows only the meaningful interpretation of the outside world, but directly, he knows nothing of the world itself.

Like the submarine operator, we come to see the world entirely through an interpretation of meaning determined by the structures of our bodies and culture. From within this structure, it is basically impossible to prove anything outside that realm of interpretation. But to the idealist that interpretive structure of meaning is the measure of all things. When operations run smoothly, things are as they should be, but if there are unknown resistances or collisions with something beyond what is understood according the structure of interpretation, these are seen as a deviation from what ought to be, causing negative emotion. In this way, the idealist hopes for a smooth ride through predictable waters, that all outside reality could conform to his structure of interpretation. To some extent we all desire ease in life, but this is neither what we get nor what we truly want.

First, this is not what we get. It is when we make ourselves the measure of good and evil (Gen 3:4-6) that the world, which exists independently of our minds, contradicts our expectations. To those who have made themselves like gods, the world seems to be in rebellion against all meaning. It is because of the expectation of idealism that we so easily shift towards distrust of meaning, towards materialism. I suspect the fact that so many people today are materialists is not because they saw clearly through the illusion of meaning, but that they were disappointed by what they thought was faith, but was in fact idealism. Spirituality, to them, meant that “my desires will be manifest in the world if I have faith.” We do not understand that meaning is not the world’s alignment to our expectations or will.

Second, neither we nor operator of the submarine truly desire an easy ride. Of course, to some extent we desire the stability of a predictable world and to have our needs provided for, but that is not the greatest good we seek. So why would anyone desire resistance from the world, or faults, or crashes, or even death? The answer to this odd claim we will explore throughout this article, but for now, imagine the boredom of the submarine operator, nothing will be new, nothing will be surprising. He is the lord over his realm. He will realize that he has no reason to believe anything exists outside of his operations of levers and buttons, for they all conform to his will. All of the sudden he no longer has interest in even operating the machine, for if he is truly a in charge, there is no need for him to do anything, as the world conforms around his action. Pure “meaning” is all that exists, and somehow, it is completely empty.

The Prodigal: An Embodiment of Idealism

It is true that we are given the power to create meaning as conscious creatures. But our power to create meaning is not so that we can selfishly conform the world to our own meaning and identity. Rather we must see our identity as a co-creator of meaning, as being given our identity as a means to come closer to the source of that identity, which is always outside of us. This is where the parable of the prodigal son comes back to give us great insight in this spiritual position. The prodigal son takes the gift of meaning for himself and cuts himself off from its source to define what is good in his own sight. Bishop Robert Barron write convincingly on this theme when the younger son demands his inheritance while the father is still living:

“This demand is presumptuous and highly insulting, for normally a son would not receive his inheritance until after his father had died. Thus, in claiming his money now, the younger son is none too subtly suggesting that he wishes his father would hurry up and die […] The parable opens, then, with the declaration of a clear break in the communion and coherence that one would expect to hold between a father and his son… By definition, a gift cannot be demanded; it can only be received graciously and as a sort of surprise. In making his demand, therefore, the younger son is precluding the possibility of a gifted relationship between himself and his father; he is cutting off the flow of grace.”

This is the sin of the idealist. He takes what is meaningful and gifted so that it can be selfishly horded. Of course, the first thing he does is leave the presence of the father so that he may hide himself and his sinful desires, thus cutting himself off from the source of meaning. The father allows this because he truly desires to give him this gift, but to be used for bringing the son closer in relationship. And in spiritual terms…

“In that sin man preferred himself to God and by that very act scorned him. He chose himself over and against God, against the requirements of his creaturely status and therefore against his own good. Constituted in a state of holiness, man was destined to be fully “divinized” by God in glory. Seduced by the devil, he wanted to “be like God,” but “without God, before God, and not in accordance with God.””

Catechism of the Catholic Church, no. 298

“Man sets himself up as the initiator of his own existence and grasps at what God desired to give him freely.”

Christopher West in Theology of the Body Explained

Because pleasures give such powerful satisfactions, and when properly ordered they point us towards eternal satisfaction, the prodigal son devotes himself to the search for eternal satisfaction in what gives only temporary satisfaction. Like the prodigal “squandered his property in dissolute living,” we squander our capacity to make meaning by focusing it selfishly on temporal goods which seem to promise eternal bliss. In turn, be become slaves to addictions, constantly needing more, no longer free to choose the good. We use people for our own ends, and eventually a famine of dissatisfaction befalls us and we end up losing both the power to satisfy our ideals even momentarily.

After squandering the gift, the prodigal son is left with nothing but an intense hunger and nothing around but the food for swine, and in this famished and humiliated state the prodigal son is hears the call to repentance, that deep hunger, was a calling not to dissolute living, but for more, to put ourselves back in communion with the source of meaning: the father.

Ideals Are for the Participation in Love

What is correct about this tendency towards idealism is that it is truly the eternal that we seek, and the repeating patterns of the cosmos, of mathematics, of the natural world, point towards an eternity outside time. But the idealist, in his venture to remove the present, the limited, and the unique for the ideal, destroys all hope to witness the eternal.

This demands a very real question. Why do we have these desires and tendency for ideals if they become such a source of frustration and selfishness? This question comes naturally if we define good merely as the world conforming to our desires. But that leads us into isolation. If we become the judge over good and evil for ourselves, we no longer receive the meaning from others. Meaning that we devise on our own is empty, and even if the world were to conform to it, like the submarine operator who without struggle cannot conceive of anything outside of his vessel, we would become disinterested in the reality outside of ourselves, complete isolation. In other words, it is more hellish to live in a world which obeys your every command, than to have one which you encounter as given and that calls you forth to adventure.

Now we come closer to understanding why Christ speaks so severely to the legalistic Pharisees compared to the more conventional sinners. I think he is showing that even when the idealist takes the gift of the father for himself, he is at least recognizing the father’s desire to be a gift to his son. The older brother, does not see this at all. He sees a tyrant who he is enslaved to, and in that way, though he for the most part keeps to the law, he is far from receiving the love of the Father.

“He who loses himself in his passion is less lost that he who loses his passion.”

St. Augustine

One of the great frustrations of ideals is that they are often the origin of sins. The materialist or the practical man will be happy to point out all the ways people, who live with their heart on their sleeves have taken risks and made mistakes. Like the older brother, who sees the danger of a life set on a passionate search for meaning, the materialist would rather stay practical and not be too caught up in dedication to anything truly Good. And those who a caught up in sin also will ask, “why did God put this desire in me, only to have it cause me to sin?”

You can ask why the father of the prodigal gave his son his inheritance knowing he would squander it in dissolute living. The father wants the son to participate freely in the loving familial economy, he allows his son to choose that or take it for himself. And though the consequences of sin are serious, the possibility for sin is also exactly what allows for relationship. This potential allows us to freely participate in creation and encounter our own limitations. That is the beginning of self-giving love.

Limitation

While the older brother remains prideful of the fulfillment of his duties, he has not even begun to participate in the relationship with the father. By making the father the limitation, and keeping to the letter of the law, he therefore encounters none of his own limitation, and he attributes his unhappiness to the tyranny of his father (“For all these years I have been working like a slave for you, and I have never disobeyed your command; yet you have never given me even a goat so that I might celebrate with my friends” Lk 15:29). In that way, he cannot see his own sin his own limitations.

Ideals play a role of motivating us to go out into the world to challenge our limitations, transforming us in the process. In receiving the gift to co-create with God, Adam was capable of naming all creatures, making order out of the world, but he was then confronted with the image of his limitation in Eve, that he would have to bend himself to another in the world. And in the Edenic state of grace and presence of God, encountering limitation was an opportunity for love and a cause for rejoicing (Gen 2:23).

It is in limitation that we find our own uniqueness, that of others, and of all creation. Because limitation draws boundaries around something, it is the cause of uniqueness. Every man is unique precisely because of the limitations he is given and those he takes on. And it is only in pressing up on his own limitation, realizing his boundaries, that he sees his uniqueness and is able to love and be loved. This requires us to accept the challenges of the objective world.

“The main condition for the achievement of love is the overcoming of one’s narcissism. The narcissistic orientation is one in which one experiences as real only that which exists within oneself, while the phenomena in the outside world have no reality in themselves, but are experienced only from the viewpoint of their being useful or dangerous to one. The opposite pole to narcissism is objectivity; it is the faculty to see people and things as they are, objectively, and to be able to separate this objective picture from a picture which is formed by one’s desires and fears.”

Erich Fromm in The Art of Loving

It is in our bodily limitation that we suffer, but it is in limitation that we have our dignity as unique and unrepeatable persons rather than being defined categorically or numerically. In our limitation and uniqueness we are loved, and not despite it. And because of this it is in suffering for the sake of the Good, that we receive Love and authentic joy. The question then becomes what does this say about God, who is called Love Himself.

What, Then, Is Meaning?

When we become idealists, we make meaning—and therefore God—into a pure idea, and so we suspect objective material to contradict God: if meaning is pure idea, what is material, since it is unique, cannot be meaningful. We fall easily from idealism to the atheism of desolation. However, this atheism is not a consequence of breaking free of the illusion of meaning; it was born from the false assumption that meaning in life exists as a pure idea unhindered by material imperfections. The idealist believes that God is only capable of being perceived in the mind, and is not made visible in creation.

However, it is in the bumps and resistances of the unique world that convince the submarine operator that he is actually doing something in the world. Meaning is not going to be smooth sailing, but an encounter with what is given as outside of you. This hints at the Trinitarian view of God. That the God of Love and meaning must not only be behind the transcendent ideals, but also the material uniqueness of that which challenges our ideals. This should remind us of the two persons of the Trinity: the Father and His only-begotten Son. Like the mind of an artist is revealed in his work, God is revealed in his Creation through his Word which brought all the world into being, spiritually and materially, in all its particularities and limitations. We must conceive of a God which is more than a Subject impossible to see and fully comprehend. While we are unable to fully comprehend the mind of another person, we are still given revelations of them through their “image,” by their incarnation, by their “word.” Likewise, we come to draw nearer to the ineffable mind by His perfect Image, Jesus Christ, and by those who image Him in creation.

Jesus enacts the pattern of the prodigal son, but without sin. Instead, he fully receives the love of the Father, and goes forth from Him, and returns by making himself a sacrifice. Despite the perfect relationship with the Father, entering the sinful world still resulted in the pattern of the prodigal son, one of suffering and return to the Father. That is because God willed the world to have its own unique existence, and though it remains dependent on Him, He allows it to become His limitation—in His incarnation—so that He may fully Love it and be revealed in it. Though Christ endured more than the prodigal, interiorly he experienced the joy of giving himself like a bridegroom for his bride, taking on limitation for the sake of Love. Christ’s incarnation is the marriage of God and material creation, and his crucifixion was the marital embrace.

It is in our imitation of Christs, the unique (only-begotten) Son, that we can embody presently the communion with the ineffable Father, the giver of our identity and meaning. When we imitate His Image, we gain the uniquely human ability to transform suffering or meaninglessness into opportunity to grow closer to the source of meaning. It is by the revelation of Christ that we can know that all of creation in its challenging uniqueness is, in fact, a route to meaning even when it leads to suffering, not in our grasping of it like the prodigal son, but in our reception of the love of the Father and offering up of our lives as a sacrifice. It is only by participating in the Son of God that we can see all creation as revealing God.

“He is the image of the invisible God, the first-born of all creation; for in him all things were created, in heaven and on earth, visible and invisible, whether thrones or dominions or principalities or authorities—all things were created through him and for him. He is before all things, and in him all things hold together.” (Col 1:15-17)