When we think of the ideas that changed the world, it is inventor that comes to mind. It was Darwin, Einstein, Marx, Newton, etc., that changed the course of history with their one big idea, wasn’t it? Certainly, these thinkers contributed something important for our culture, but should we hold them to the high regard of the title “genius,” implying that they have otherworldly gift’s others have no access to? Are they the sole movers of culture or do others play a bigger role than we give credit to?

The belief that the culture is shaped by a few individuals makes us ignore the situation that we are actually in—an active situation. We forget that we are not just consumers of culture, but its promoters, its inventors. We never think of ourselves as culturally influential because we are not celebrities or on television, but we do not realize the small effects we can have on those around us, and where those effects might lead. Believing that it is only a few people that make progress in the world, focuses us, not on what we do for the culture, but on what the so-called geniuses are doing to make the intelligent adjustments to our politics, our education, our culture, our technology, our art. We become critics of those who we are relying on for change. All true innovation seems impossible for the average man or woman, and so we forget that, we are making an impact—big or small—on the culture, regardless of what we intend.

The First Type of Error

When we believe that only the gifted make a difference, it is easy for us to resign, thinking that it is impossible to make a meaningful difference in our social world and that all culture belongs to the elite, the gifted. It then seems our only role is to consume the innovations of big influencers and use their ideas for entertainment, for curiosity, for leisure. We think very little about our active role in the culture.

Being resigned to a passive role in culture we become focused on ourselves, our discomforts, our inconveniences that others couldn’t solve for us. All the things that we wish to solve are things which a genius inventor needs to come up with for us.

This passivity may seem like an innocent want of leisure and comfort, but it is also a reaction to the feeling that one does not have an effect on their community, that one cannot solve problems him or herself. Ironically, most of our culture, one of leisure and passivity, is created by those who do not think they influence the culture.

We lose the intention of our lives when we follow what the authority of “genius” gives us. It seems to give us a present, but it charges us later. It charges us by wiping our ability to give, to create. We pay with resignation.

The Second Type of Error

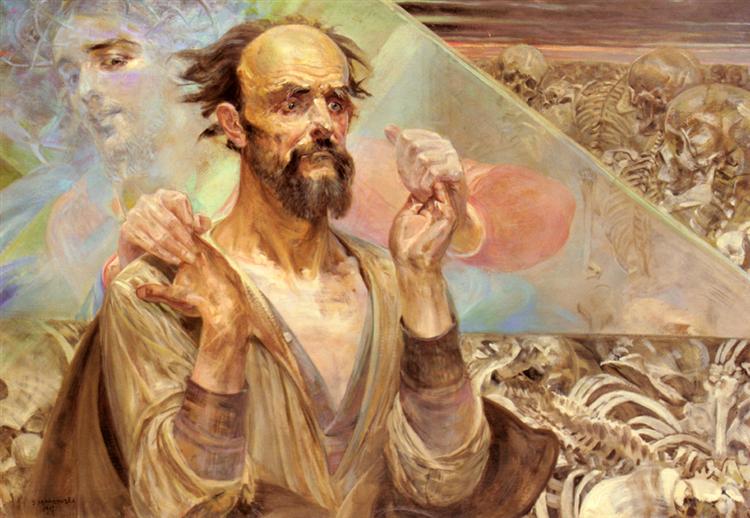

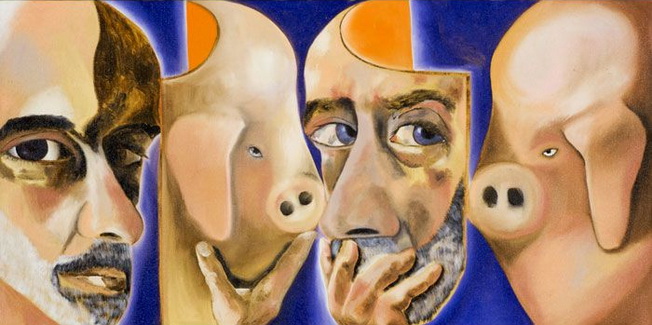

Alternatively, we can hold the belief in “genius” and still strive for making a difference. Rather than being an excuse to be passive, it serves as a roadmap to influence. When we discover that the only way to create impactfully is to be named “genius” and to appear as one, we attempt to merely attain the image of genius rather than the ethic of genius. Our efforts towards looking genius are greater than our efforts towards whatever we are interested in. Our image becomes the tool—a vacant and pretentious tool—for making a cultural impact.

In this way, your beliefs make it impossible to have a meaningful impact in your culture without being hailed as a genius. For one to convince oneself of one’s genius, one must act like a “genius” to achieve the credibility required for influencing the culture. Your confidence rides on how much you fit the mold of what a genius ought to do and be. And this image that you seek will be from very distant perceptions of what a genius appears to be.

Not only will this make you rotten company, but it will frustrate you, your defensiveness of keeping your appearance will defend you from learning from mistakes or even noticing them. The goal for this person is to maintain the illusion of genius, even without making a truly positive impact on culture. Someone like this will be a harsh critic without having been a creator himself. All modest efforts become trivial, only the eccentric and ostentatious displays are meaningful. He will take himself too seriously to allow himself to be wrong and will be forced along by his current beliefs whether they are good for him or not. He will never consider the fact that important actions are not always done only by those important figures, and never are they done by those who rely on their image of genius rather than their passion for their creative domain.

On this path one can still succeed in convincing others in their effect on the culture, but one never becomes positively effective. The only influence he might have will be on those making the first mistake, of electing the passive route of resignation. The two mistakes in believing in the authority of “genius” sustain each other.

An Alternative Belief

The alternative path is much more hopeful that the first, and more honest than the second. We must realize that innovation and cultural evolution happens on a wider and deeper scale. Change happens with the zeitgeist, the spirit of the times, which allows and propels the important ideas. It may seem like obvious knowledge that only a few gifted individuals make cultural change, but if you consider some classic examples of “genius,” you may find that it is not as simple as that.

The invention of calculus occurred twice independently and simultaneously; that is not a coincidence; the culture was the background for the invention, even if it did take two people with exceptional intelligence to write it all out. Darwin’s ideas of natural selection had also been separately articulated around the same time. Darwin gets most of the credit because he had a vast collection of data and writing that better articulated his new idea in biology. But the idea was sure to come. In contrast to the progress of knowledge, Archimedes knew more about the solar system than what people knew over one thousand years later; that is because the culture had forgotten the knowledge of ancient Greece; the culture changed, and the great idea was lost for some time. This was not a measure of Archimedes’ genius but a measure of how much impact the rest of us have on ideas, of how cultural acceptance can rule over genius.

It is only the culture that can allow new ideas to come in and be great, the culture has more say than the individual when all is said and done. The genius is not isolated. Sometimes it takes time for culture to catch up to the individual creative, but often it is the individual who is first given the tools and freedom of thought by culture. Some of the great ideas of past creatives would not be known had the culture not allowed them to become popular. Consider how easily it would be for some great ideas to be lost if the individual “genius” had lived in a different culture. If Socrates were living in America today, would he make the same splash he did over two thousand years ago, or would his ideas be labelled insane? Which great ideas have we temporarily forgotten today because of our culture? Are these ideas even still great if no one recognizes them? Have they failed the test of culture? Or has the culture failed to appreciate them?

So, what does the person who understand the role of the zeitgeist do? They do not put on a mask of genius to give off the illusion of influence. They do not resign thinking that their actions have no consequences. They do not try to be radical or over-ambitious, because they know that what could be best for them is right in front of them, in their relationships and community, not some vague goal of becoming a “genius” to change the culture.

The person who understands her role in cultural evolution allows people to explore. Half of the work she does is to encourage and teach others, the other half is exploring and creating herself. She is open to new ideas and encourages those who have dreams of pushing forward a field of inquiry. She will realize the impact of the everyday actions, no matter how banal or trivial. The goodness of small and modest actions is better than the vagueness and inaction of the so-called genius. Perhaps we don’t get credit from those who still believe in “genius,” but that was never her goal. We would rather have many kind and honest voices instead of one loud one.