In the last article, I made the argument that living beings exist with inefficiencies that make cognition flawed. That is a necessity because that is nature’s only path to adaptation to potentially novel conditions or honing in on predictable conditions. Unfortunately, the fact that life is designed with necessary imperfections makes our mission of judging cognition difficult. Being wrong is a necessary step to adapting. When being wrong is part of the plan of life, we run into a nihilistic roadblock in our basic understanding of embodied cognition. I want to acknowledge the positive, beautiful aspect of the problem, its alure, and to eventually argue how we need to find higher order in life.

The Cyclical Theme of Adaptation

Life and nature often work in cyclical patterns. This is especially true in the processes of evolution.

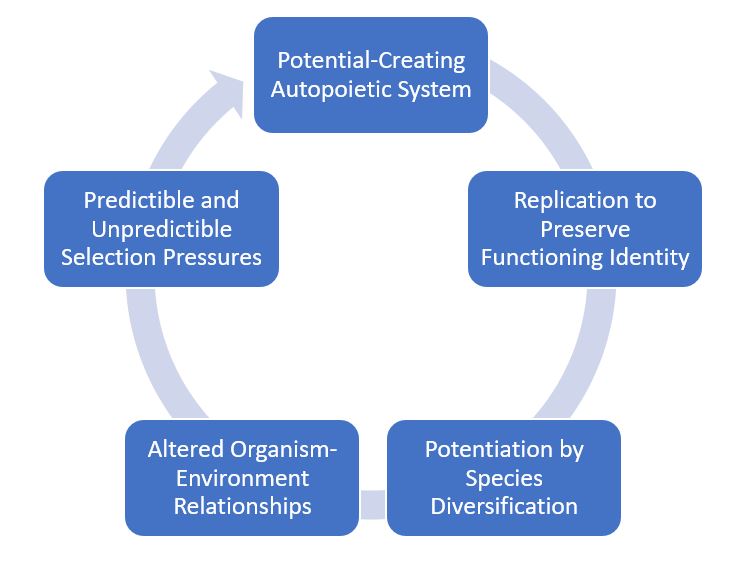

The goal of the individual organism seems to be to continue self-organizing, to extend its life as a separate unity within the world. We intuit that an organism is acting with knowledge if it successfully continues its self-making processes. So proper cognition appears to be the interactions with the environment that allow the self-making process to preserve the identity of the organism. The measure of this mostly simple: how healthy is the organism.

However, eventually that particular life comes to an end regardless of its preparedness for its environment. The organization is lost unless the organism replicates its organization in other life. This makes the previous goal of the self-organizing organism to be aimed at the further goal of reproduction. We can now see that the process of self-organizing is a means to another end. Our measure of cognition contains a goal of expanding the potential existence of one’s organized identity through generations. Already the measurement of this aim of cognition is confused by the difficulty in measuring potential when the future is unknown.

But it is not conserving identity for identity’s sake, otherwise we would all still be the very basic first replicating organism. The diversity of life speaks to another aim of the evolutionary process. The best way for an organism to improve the potential of its genetic relatives is by giving them diverse characteristics. That way, when the environment changes, at least a few may be able to survive thanks to its unique characteristics. This threatens the aim of potentiating genetic identity by altering that identity at every generation, but it is also necessary to even retain potential survival in a chaotic world.

The goal of the altering genetic identity appears to be to create an individual with better cognition according to the autopoietic goal that we began with. Unfortunately, the cycle continues when you ask what is the biological purpose of this adapted ability to self-organize: it is to replicate, and create more potential. For what end?

The way we have defined embodied cognition is by how well the organism achieves its goals in its interaction with the environment. But we find the equipment for cognition itself is not made to seek any one particular definable goal; instead it is dispersed between the individual, its genetic identity, and for life as a whole system. So far, there is no defined progression, no standard to aim at. Our only measure is what exists, for all that exists is somehow justified by being a lottery ticket to future existence no matter how improbable.

The Flattened Judgement of Cognition

Because the measure of cognition from this viewpoint of nature is what exists here and now, everything in existence has equal validity as a representative of embodied cognition. We do not know the quality of an adaptation until it is able to reproduce itself, and after that the measure is solid. Further, no matter what maladaptations the organism has, it can be regarded as a potential adaptation to the future, only passing time will tell. Or, at the very least, the organism represents a necessary mistake, like in the manner that we require several bad ideas before having a good one. As a result of the unpredictability of the future, each divergent change to the organism is both burdened with traits that is potentially deleterious and provided a potential key to succeeding in the unknown future.

For instance, who would have guessed that small mammals would be better adapted than dinosaurs before the unpredictable cataclysm that made it so? From the biological perspective we cannot judge what is adaptive and what is not, we cannot see all ends. In fact, many “maladaptations” that make one susceptible to genetic disease are beneficial in other unpredictable ways. Sickle cell anemia is adaptive to prevent malaria and hemochromatosis protected people during the Black Plague. Anyone would see those as maladaptations, and without malaria or the plague, they would be. But as luck would have it, they were adaptive. How could we possibly judge what variations would work? We cannot wait until all the votes are in, they never are.

This is a problem for our understanding of cognition, but first I want to defend the temptation to become content with this position, because it has an alluring truth to in in how we think today.

The Musical Theme of Nature

To understand the teleology of nature and evolving creatures we can use a musical improvisation metaphor. Think of the identity preserved through the generations of an organism, not as its conservation of genes, but as the abstract essence that all its variations point to. The main theme of a song is often abstract: it may have been played once, but afterwards all its manifestations are in the form of variations on the theme. In this song (which reflects life), the theme is never again exactly played but is pointed at throughout the song. Likewise, the “quintessential” autopoietic organism only existed once, and the rest are variations on it.

Nature and evolution have a similar strategy of selection as the musician who improvises upon a theme. If the theme works, the musician will repeat its manifestations, adding variation to keep interest in what would be a bland theme (if it were repeated variation). Each variation is both the potential for capturing interest and potential for making a mistake and overburdening the song with clutter. Likewise, the organism, instead of trying to maintain its exact relationship to the environment, tries to find favor in the future environment by playing with unpredictable genetic changes, but does so with scattershot and risky variations.

Many repetitions and variations are done before selecting one to make the new theme for continuing of the song. This would be how an organism would prove its cognition by surviving and reproducing. If this metaphor were mirror nature, multiple variations could be chosen but branch into different songs, but for simplicities sake let us focus only on one path. In a way these variations of the theme are actually what maintains the theme. Although the variations are different and rebellious, they still serve to maintain the interest in the original theme which exists now only in the fact that the song has continued. Likewise, variations in organisms support the original parent identity by varying around the theme of its parent in a way that maintains the identity which works and is predictive of the unknown future environment.

The selected variation of song or organism is then repeated again, then improvised further off of. Each selected variation becomes the new theme. To aim at that theme is also to aim (slightly less) at the previous one. But eventually the original theme becomes unrecognizable in the present manifestation. In attempting to preserve is the theme of a long song, the theme is lost in the variations. Likewise, an animal’s natural origins in deep history are practically impossible to identity in the animal today, but we know it is there.

I used this metaphor because it makes the process of nature look beautiful like a well-improvised song, and it is beautiful, despite its aimlessness. Each variation on this hypothetical song is not progress, it does not lead to any end. We cannot judge one variation compared to another because all that exist are variations on one that worked, and those that didn’t work were good and necessary experiments which could not have been judged until after they were heard.

Although such a composition is beautiful, as nature has beauty, it remains unsatisfying for presenting a telos or a resolution on a theme. Each new variation has aims that are in favor of preserving its recent parent, which changes every generation. The goal is not stable, and “truth” is relative to the individual organism. It is aimed at what works at each “generation” of the song to keep interest in the listener. Each iteration becomes relative to the last iteration.

The songs we love almost always come back to a theme. This is the musical need for a stable goal. That is the problem we have to solve. How do we create a stable goal for cognition to work towards and be judged by?

Nature’s Hostility Toward the Individual

Before hinting at a solution, I want to continue down the consequences of this cyclical and relative way of looking at the world. Already, there is no place to stand on firm ground to judge cognition. That would not be a problem if life were a harmonious song. But the musical metaphor falls short on some of the darker elements of nature.

First, individuals are burdened with maladaptations in case they benefit us. We’ve covered the fact that organisms are not evolved for perfect fit to their environment, because they, as carriers of maladaptations, are posited as potential survivors of the unpredictable future. Nature’s strategy here is to balance the organism between reliable autopoietic processes, and burdensome inefficiencies in case unpredictable things happen and those burdens can be adaptive. This is all at the expense of the individual organism, but better for the survival of the species.

Second, nature requires passive compliance. There is no place for individual judgements. When nature places bets on individuals to carry genetic identity, she requires that the individual follows the path that the variations lead it. Choice would ruin the experiment. From the perspective of nature, we need to do whatever our bodies tell us, because evolution builds organisms to play the odds well enough. The mythologies of ancient peoples have female deities of nature which swallow up the individual, make him go mad, make him passive. They help us to understand that the processes of nature desire us to be passive and when consciousness is born, nature is outright hostile to individual cognition.

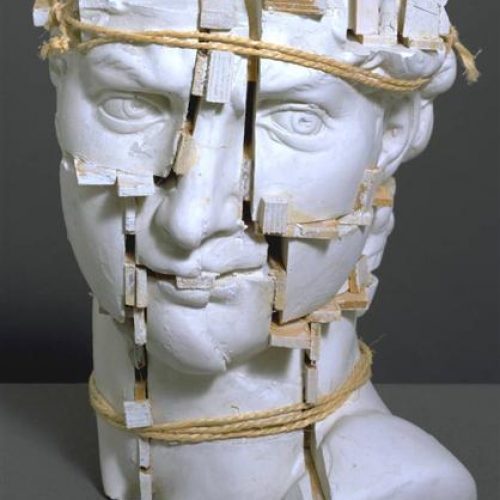

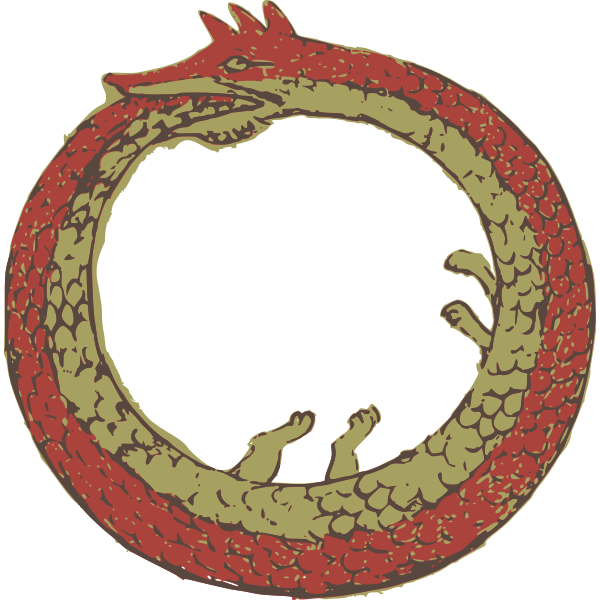

Third, consider the necessary death required for adaptations to happen. Nature is wasteful of its organisms. The vast majority of organisms have no success; they were ill-conceived variations that were necessary to stubble on a good one. Each positive adaptation costs many lives of individuals. Nature kills her bad ideas and reuses their pieces. That is why the uroboros is an apt symbol of nature before consciousness. It is a serpent that devours its own tail. To use the musical metaphor is to take this too lightly, as if all nature is in harmony, but the harmony is made from the sacrifice to create the beautiful elegance of a complex adaptation.

Fourth, nature has a tight ecosystem which one could call harmony. But the frugality of nature means that some organisms do the selecting for her. We have predators and prey. We have decomposers and the dead, and all life relies on these systems. We do not mind so much in “The Lion King,” when Mufasa says that the lions eat the innocent antelopes because that is just the circle of life. But that judgment can extend to justify anything. Because of nature’s wisdom and tightly-bound ecosystems, we can justify anything as nature’s way of balancing itself. Murder is justified from nature’s perspective; it feeds the soil with blood. That is why early civilizations practiced mass animal sacrifices to female deities to ask for better harvest yields. It often is not neutral to worship nature, because it necessarily relates to death worship.

It may be for these reasons are why Carl Jung says the unconscious (the nature within us) is collective and cares not for the individual, but the collective. The next article will make an attempt at a teleology that we can use to ground ourselves even in the face of this enormous threat of nihilism and suffering.